The larger issue is that Netflix controls information that helps determine content, giving it a crucial advantage in negotiations with producers, actors, writers as well as keeping it ahead of competitors - and which is central to the current Hollywood strikes over the role of AI. JL

Christopher Mims reports in the Wall Street Journal:

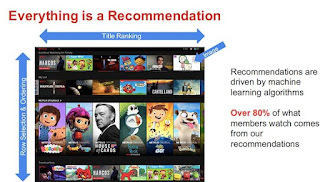

The proprietary technology Netflix uses to gather and analyze data remains key to the company’s success. That data is used to inform decisions about what shows and movies to produce, whether to renew them, and whether to share them with any given viewer through the company’s famous recommendation algorithms. Netflix’s commitment to scripted shows - last quarter, scripted titles represented two-thirds of shows Netflix renewed - suggests the company has found that they return their investment in attracting and retaining subscribers. “As people who are making content for Netflix don’t know the value of their labor, Netflix has an advantage at the negotiating table. Data is central to this.”After decades of pitching Netflix NFLX 3.05% as a technology company that happened to distribute entertainment, executives there have lately attempted to restyle their streaming behemoth as an entertainment company that happens to rely on technology.

But don’t be fooled: The proprietary technology that Netflix uses to gather and analyze data remains key to the company’s success. That data is, in turn, used to inform decisions about what shows and movies to produce, whether to renew them, and whether to share them with any given viewer through the company’s famous recommendation algorithms.

That’s true whether the content is new and original—such as “The Queen’s Gambit,” “Squid Game” and “Money Heist”—or it’s part of an existing franchise, like “Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story,” the “Gilmore Girls” revival or subsequent seasons of hits like “Stranger Things.”

Netflix already shares some of this data privately, with those who make its content, and in the form of public weekly top-10 lists, says a Netflix spokeswoman. Depending on how the simultaneous strikes by Hollywood writers and actors go, the company, and its many imitators, may have to share more.

That’s because, in the age of streaming, answering the question of how actors and writers should be compensated depends on this data, and how the company uses it to calculate whether a show was a good investment.

Data as bargaining chip in labor negotiations

When residuals come up in the context of a contract negotiation, such as the one at the heart of the current Hollywood strikes, what’s really at stake is data, and who possesses it, says Michael Wayne, an assistant professor of media and creative industries at Erasmus University in Rotterdam.

The Writers Guild of America and SAG-Aftra, the actors’ union, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Wayne points to “House of Cards,” Netflix’s first big original series. Even 10 years after its debut, it still has value for the company, but how much isn’t clear.

“As long as people who are making content for Netflix don’t know the value of their labor, Netflix has an advantage at the negotiating table,” says Wayne. “Data is central to this.”

Netflix has in the past few years begun sharing more data with producers, according to a spokeswoman for the company, and a letter Netflix sent to a U.K. parliamentary committee in 2019. This data includes how many people started a series or movie in its first seven and 28 days on the service, and also how many completed it in that time.

Netflix also has a program allowing tens of thousands of its subscribers to give early feedback on some titles, in hopes that it will encourage those who create them to change them to fit viewers’ tastes.

Hollywood talent might hope to change this situation. But the current reality is that, beyond these limited disclosures, Netflix has no incentive to be transparent about its proprietary internal data, says Marshini Chetty, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Chicago who has studied how the company gathers data.

Netflix’s data advantage

Netflix’s ability to use data has helped it in the streaming game of retaining subscribers with original content, without breaking the bank. It added a healthy 5.9 million subscribers in the latest quarter and its profit rose, the company said this month. It credited a crackdown on password sharing—and also bragged that it had the top original streaming series in the U.S. for all but one of the first 25 weeks of 2023. By comparison, Disney and other rivals have been losing money on streaming.

A recent California law offers a peek into Netflix’s data gathering and how it might be able to use that to its advantage with both streaming rivals and its talent negotiations.

The California Consumer Privacy Act, which took effect in 2020, requires companies to provide customers, on request, with the data it has about them. Doing so with Netflix reveals data with a surprising level of granularity, says Brennan Schaffner, a computer-science Ph.D. student at the University of Chicago.

That data includes “detailed accounts of every piece of content you’ve engaged with since you created your account,” says Schaffner, including how long you watched, where you were when you watched, and what devices you used. Netflix also has unprecedented insight into what led you to watch something in the first place, in the form of detailed records of how you navigated the service’s menus, and what you clicked on.

Netflix has explained that this data powers its recommendation algorithm. The company has also alluded to this data in past discussions about how it tests different versions of previews, thumbnails and other content.

How data shapes content

One window into how Netflix uses data is to look at how the company decides what to renew.

On average, a show on a traditional broadcast or cable network that gets renewed goes to six seasons, says Olivia Deane, a senior analyst at Ampere, an analytics company that gathers data on media and entertainment.

At Netflix, however, shows typically only get renewed for a total of three seasons. This has been true since at least 2020, she adds, even though you would expect that figure to go up over time, as the years roll on.

This suggests that titles that go beyond their third season have limited utility in terms of both attracting and retaining subscribers, says Deane. (To be sure, Netflix does have some long running series—“Big Mouth” has been renewed through season eight.)

Netflix’s ongoing commitment to scripted shows—in the last quarter, scripted titles represented two-thirds of the shows Netflix decided to renew—suggests that the company has found that they return their investment in terms of attracting and retaining subscribers.

Netflix has detailed data on every movie or show you’ve ever watched on the service, including where you were, what devices you used, and how you navigated its menus to get to them.

Given that scripted titles cost far more to produce than unscripted ones like reality shows and documentaries, this shows that Netflix’s advantages in data—which the company has said give it more confidence that audiences will show up for the company’s content—continue to pay off.

A prime example of Netflix’s content strategy is “Stranger Things,” says Deane of Ampere. First, it’s the kind of pricey scripted programming that Netflix has considerable success betting on in the first place, owing to its data-driven insight into viewers’ tastes. Then there’s the fact that there have only been four seasons of the show. (Its creators have expressed a desire to create a fifth, but no release date has been set.)

Netflix has the ability to track individual subscribers, and when they churn—that is, cancel their subscriptions—and that data suggests to analysts at Ampere that a steady supply of splashy new shows can both attract and retain subscribers, but there are diminishing returns for continuing even beloved franchises.

Netflix’s head of content, Bela Bajaria, said in a June address to the UCLA Entertainment Symposium that “algorithms don’t decide what we make.”

“There’s not an algorithm that would probably say, you know what’s a great idea? A period show about a woman playing chess,” she added, referring to the award-winning series “The Queen’s Gambit.”

Algorithms also aren’t creating content for YouTube, TikTok or Instagram—and yet all these platforms are in some sense ruled by their respective content-filtering algorithms. That entertainment platforms still rely on humans to watch trends and come up with original ideas is not surprising. Bajaria’s comments don’t address the way that data can shape decisions about which human-originated ideas to green-light—as outlined by Netflix’s own engineers—nor about which shows and series to produce more of.

Tighter budgets, more machine learning

“Budgets are becoming tighter, and where you spend your money is becoming more and more important,” says Deane. “I think that’s why Netflix is now using data more than ever.”

Netflix’s budget for content stayed flat between last year and this one, at around $17 billion.

Netflix, a bellwether for the entire streaming industry, is hardly the only streaming company to operate in this way. Leaders at competing services have talked about how they use data to make decisions about what to produce. As more of these streaming services explore offering an ad-supported version, gathering this kind of data becomes mandatory, so they can provide advertisers with viewership information.

Now more than ever, series and films are expensive. This is all the more reason to have AI to inform the decision to commission them, as Netflix’s own engineers explained in a 2020 blog post about how the company uses machine learning. That AI can be fed information about what titles are comparable to a proposed one, and what audience size to expect, and in which regions. Doing this requires the application of transfer learning, knowledge graphs, and a host of other techniques which are now standard in cutting-edge AI systems—such as Google’s Bard and ChatGPT—but which are not exactly the usual fare of Hollywood studio pitch meetings.

The more data Netflix has to feed such an AI, the better the results it will issue. As we’ve seen with the enormous volumes of data fed into today’s generative AIs, sheer scale can yield surprising and useful new capabilities.

0 comments:

Post a Comment