Robert Klara reports in Ad Week:

At 83.1 million, a quarter of the U.S. population, millennials are now the largest single consumer group. "We’ve generalized them as a certain type of person, [but] companies are starting to understand, ‘we’re not getting the ROI we thought we might.’”Millennials are saddled with very large expenses that reduce their spending power. 88% live in metropolitan areas. And city rents tend to be high. (Also) they have $1.53 trillion in student-loan debt. The economics of the consumer are the most singular driver of behavior. People behave more like their income than their age.

As a generational expert with over 25 years in the field, Alexis Abramson has heard about all there is to hear from brands trying to appeal to various age groups. From baby boomers to Generations X, Y and Z—pick your group, and she’s researched them, written about them and (probably) lectured brands on how to attract them, too. In recent years, a good many of those brands have had their sights set on the generation born between 1981 and 1996: millennials, aged 23-38 today. That’s because at 83.1 million, a full quarter of the U.S. population, millennials are now the largest single consumer group out there. Simply put, few companies can afford not to court them.

But ask Abramson how brands feel about millennial consumers these days, and the answer might surprise you.

“There was a great deal of interest [in millennials],” she said, “but there wasn’t as much due diligence around that group. We’ve generalized them as a certain type of person, [but] the reality is the rubber is meeting the road. Companies are starting to understand, ‘Wow, we’re not getting the ROI we thought we might.’”

Abramson isn’t a voice in the wilderness. Her analysis joins a growing body of evidence that suggests that millennial consumers, for all their size and savvy, haven’t exactly been the boon that many brands expected them to be. That’s not to say that millennials aren’t all those compelling things that innumerable articles and reports have brimmed about: digitally native, mobile oriented, media savvy, politically progressive, ethnically diverse, well-educated and culturally savvy. Millennials are, indeed, all of these things.

But a troublesome detail has been persistently overlooked over the last decade of wooing this crowd: Millennials—many of them, anyway—are strapped for cash.Source: Deloitte

That’s one of the takeaways of a brand new study from Deloitte’s Center for Consumer Insight, which surveyed over 4,000 American consumers to determine their current consuming habits. And when it came to millennials, one statistic stuck out: Since 1996, the average net worth of consumers under 35 has dropped by 35%.

Surprised? So was Kasey Lobaugh, Deloitte’s chief innovation officer for retail and distribution. He highlighted that while companies have been busy focusing on millennial spending habits as they relate to personal identity or cultural factors, what they really need to pay attention to is the millennial wallet.

“[If] you think about the narrative in the marketplace around the changing consumer and the millennial, there’s very little focus on the behaviors that are driven by economics,” he said. “There’s a narrative driven by some kind of cultural change. One of the things that really shocked me is that the economics of the consumer are really the most singular driver of behavior.”

In other words, he said, “people behave more like their income than their age.”

Was marketers’ faith in millennials misplaced?

In the years since brands began buzzing about millennials in the early 2000s, a number of rosy generalizations about them have taken root. Take this appraisal from the Obama White House published in 2014: “Millennials are a technologically connected, diverse and tolerant generation. The priority that millennials place on creativity and innovation augurs well for future economic growth, while their unprecedented enthusiasm for technology has the potential to bring change to traditional economic institutions as well as the labor market.”

But now that millennials are in that labor market as fully vested consumers, a slightly soberer picture is emerging about their buying power. The problem is not their size, as millennials represent a larger consumer group than the baby boomers. And it’s not the block of money they control, as millennials spend about $600 billion a year and are on track to spend $1.4 trillion by 2020, according to Accenture data.

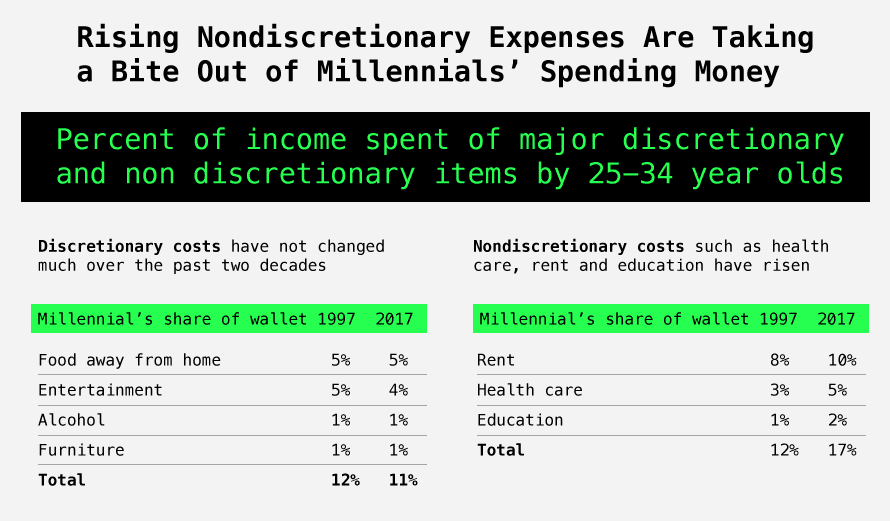

The problem, rather, is that millennials are saddled with very large and unavoidable expenses that reduce their spending power when it comes to the discretionary purchasing that gets marketers so excited.

Expenses … like what? Data from Deloitte and other sources points to at least two major factors that are impeding millennial spending power right now: housing and student debt.

We’ll take on housing first. In 1997, according to Deloitte’s study, Americans aged 25-34 spent an average of 8% of their income on rent, but by 2017, that figure had risen to 10%. (If those figures seem low, it’s because they are average household, not individual, figures—and not all millennials are paying rent. That said, it’s a significant bump nevertheless.) One reason for the increase is the millennial penchant for living in cities. According to a Pew survey released last year, a staggering 88% of millennials today live in metropolitan areas. And city rents tend to be high.

Historically, one way to beat the greedy landlord at his game—and build up personal equity at the same time—is to buy a home. But millennials aren’t buying homes, at least not in the numbers that previous generations did. According to the Urban Institute, in 2015, the home ownership rate for Americans aged 25-34 was 37%—8 percentage points below the rates for Gen Xers and baby boomers.Source: Deloitte

“Of the 13.5% of millennials that are heads of households, only around 50% of them own their own homes,” said Ron Cohen, vp of product strategy for consumer analysis firm Claritas, citing his own data. “The other half are renters—many likely with roommates to share rent and other expenses.”

“We have seen a drop in home ownership,” Deloitte’s Lobaugh added. “It’s not that the millennial somehow doesn’t want to own assets. But what we lose sight of [is] the bifurcating economy. After the downturn [of 2008], it became harder to get a loan. The population that couldn’t get access? They’re renting now.”

The recession that never really ended

In fact, while the 2008 recession was an economic broadside to most Americans, the millennials took an especially hard hit—and have yet to fully recover from it.

Timing is everything in life, and if you were born in 1989, that meant you were getting out of college and entering the job market just as the global economy was tipping over a cliff. Assuming you found a job at all, the job you did find wasn’t going to pay as well.

Mike Shedlock, an investment advisor with SitkaPacific Capital Management, points out that Americans in the workforce during 1970s and 1980s “got huge wage increases. [But] look at the millennials now. If they begged, they’re going to get a 3% raise. It’s impossible for them to catch up.”“After the downturn [of 2008], it became harder to get a loan. The population that couldn’t get access? They’re renting now.”-Kasey Lobaugh, chief innovation officer, Deloitte, on millennials renting instead of buying homes

Among the economic watchdogs to note consequences of this late start is the Federal Reserve. Its Demographics of Wealth Study released last year found that the wealth of families headed by someone born in the 1980s—essentially half the current millennial generation—is 34% below the track established by earlier generations. This group, the bank stated, is “at the greatest risk of becoming a ‘lost generation’ for wealth accumulation.”

“One big issue in our world right now is income inequality, and I think you’re seeing that way more in the younger generation,” adds author and consultant Dan Schwabel. Largely because of the 2008 recession, millennials “had a delayed adulthood,” and as a result, “they’re making adult decisions later in life.”

Millennial consumers, Schwabel added, “want the same things as the older generation, except they have to make short-term financial decisions to have a chance of having that kind of life. And it will take them longer. Not only are they getting paid less, but the big elephant in the room is they have $1.53 trillion in student-loan debt.”

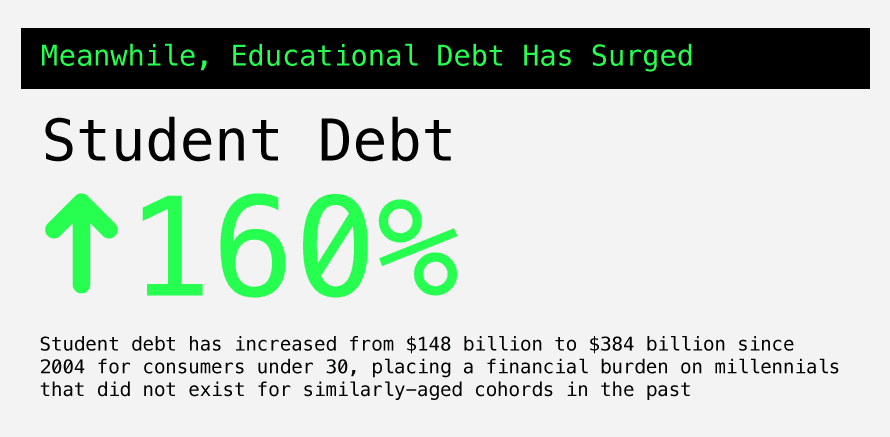

Source: DeloitteThe higher cost of higher ed

Ah yes, student loans. Debt was already a huge problem for millennials. According to research performed by the George Washington University School of Business, 66% of millennials have more than one type of long-term debt, and nearly half (48%) say they live paycheck to paycheck. But no single drain on the millennial wallet is greater than educational debt—most often, the servicing of student loans.

It’s worth pointing out that people with educations earn significantly more over a lifetime, and millennials are thus far the best-educated bunch in American history. According to Pew research figures, 36% of millennial women and 29% of millennial men have a bachelor’s degree. (For Gen X, those numbers are 28% and 24%, respectively, and for boomers, it’s 20% and 22%.)

But for millennials, the cost of those diplomas has been especially dear. “Between 2004 and 2017, student debt rose 160%,” Lobaugh related. “Think about that. People are more educated, but we have stagnant wages. The ROI on education isn’t materializing the way they might have hoped.”

It sure hasn’t. According to data from brand-strategy firm Padilla, one in four millennials who carry more than $30,000 in educational debt expect to be paying that debt down for the next 20 years. And that puts a crimp on discretionary spending. Nearly a third of millennials (30%) in that much debt report that they’ve had to put off a vacation because of it, 31% say they’ve put off buying a car, and 41% say they can’t buy a home.

Less money for the fun stuff

Little wonder, then, that Deloitte charted declines in millennial spending when it comes to certain discretionary items—the sorts of declines that leave brand marketers to have second thoughts about all this millennial targeting.

For example, consumers aged 25-34 spent a little more than 5% of their income on apparel in 1987—but as of 2017, that figure was 3%. Discretionary spending by millennials in other categories (alcohol, eating out) has remained flat over the 20-year period between 1997 and 2017. And while marketers have gushed for years that millennial consumers prize experiences over material things, the fact is that spending on entertainment is actually down.

What’s happening is that obligatory costs such as healthcare, housing and student loan payments are sucking up the money that millennials would rather be spending on consumable items.

Considering all of these forces at work, Mike Shedlock, who also writes a blog on global economic trends, has cooked up his own name for the millennial age cohort. “The screwed generation—that was the term I came up with,” he said. “I believe they are.”

Which begs an important question: If millennials aren’t able to be the full-fledged consumers that so many brands want them to be, why do marketers keep courting them? Does it make sense to advertise to a group with comparatively little money to spend?“The screwed generation—that was the term I came up with. I believe they are.”-Mike Shedlock, writer on global economic trends, about millennials

“It makes sense to me,” Shedlock said—at least, if the items being marketed are relatively inexpensive lifestyle items like iPhones, Nintendos and Fitbits. “Look at the things millennials can afford to buy,” he continued. “They’re not buying homes and cars. They buy gadgets.”

Meanwhile, Abramson recalls what happened when the gaming industry decided to target millennials the way it had gone after boomers. Casinos, she said, looked at millennials and thought, “Wow! This marketplace is huge! They’re adventurous!” But then the millennial customers who came to the casinos brought their own alcohol, packed several friends into a room and generally didn’t spend much money “because they’re dealing with school debts that are quite high.”

The problem, Abramson believes, is that brands drunk on boomer spending rushed in for the millennials before stopping to consider what made that group different—and, in many ways, poorer.

Companies, “saw the ROI for boomers,” she said. “They saw immediate results. They got very excited about it.”

Then they thought, “Oh gosh, let’s look at the next big thing—that was millennials.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment