But whether it does or doesn't, the opportunity to become the Amazon of transportation is gone, Uber's world is more complicated and success is less certain. JL

Ben Thompson reports in Stratechery:

There was a simplicity to the brutality of Uber’s original strategy: be as aggressive as possible to establish an early lead, and then leverage Uber’s ability to raise money to spend its competitors into submission. The bundling of services for users, for drivers, and of self-driving makes sense as an alternative.This strategy is more complicated, and the chances of success — and, of profitability — lower. (But) the more Uber can handle all of a user’s transportation needs, the stickier Uber becomes for consumers.

Start with profitability, or the lack thereof: two weeks ago the company reported its quarterly “earnings” and once again the losses were massive: $891 million on $2.8 billion in revenue. Clearly the business is failing, no?

Well, like I said, it’s not that easy: unlike a company like MoviePass, Uber has positive unit economics — that is, the company makes money on each ride. This is clear intuitively: Uber keeps somewhere between 20%–30% of each fare, from which it pays insurance costs, credit card fees, etc., and keeps the rest.

According to last quarter’s numbers “the rest” totaled $1.5 billion, for a gross profit margin of 55% (13% of Uber’s total bookings). Moreover, margin is improving — it was 47% a year ago — mostly because Uber is managing to both take a higher percentage of fares even as it has reduced its spending on promotions and driver incentives (Cost of Revenue, meanwhile, appears to correspond very closely to gross bookings).

The problem for Uber is trifold: first, the company continues to spend massive amounts of money on “below-the-line” costs: $2.2 billion for Operations and Support, Sales and Marketing,

Research and Development, General and Administrative, and Depreciation and Amortization. Second, it seems likely that a good portion of the company’s improving margin stems from exiting more difficult markets like Russia and Southeast Asia, as opposed to improvements in its core markets in the United States, Europe, and Oceania. And most concerning of all, Lyft seems to be outgrowing Uber.

Uber’s Lyft Problem

Lyft is a problem for Uber with riders, investors, and drivers.

From a rider perspective, Lyft has, unsurprisingly, benefited from the self-inflicted disaster that was 2017 (although to be fair, 2017 was the year of revelations of problems that had been in place for years). The consumer benefit of services like Uber and Lyft has always been clear, and Uber’s aggressive expansion paid off when the service became the default choice for a large portion of the market, something that is critical for a commodity offering with two-sided network effects. The problem is that Uber gave riders plenty of reasons to question their default choice with not just a sexual harassment scandal, and not just a lawsuit alleging the theft of intellectual property from Google, and not just allegations of brazenly circumventing local regulators, but all three (and honestly, this understates things).

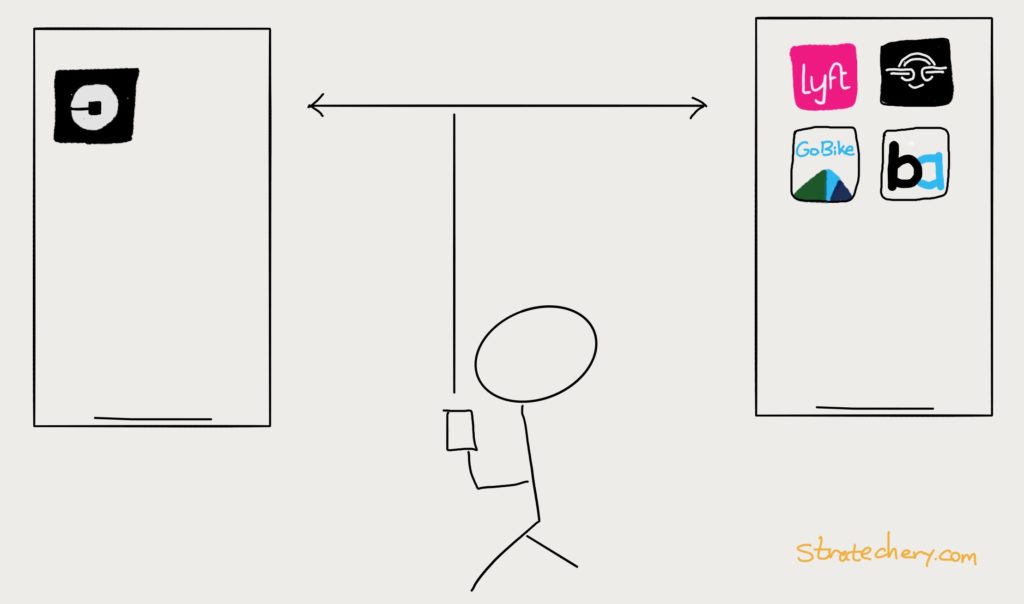

This was particularly problematic because that two-sided network effect wasn’t that strong: sure, Uber was more likely to monopolize driver time given its larger user base, but as long as drivers are independent contractors Uber can’t do anything to prevent them from multihoming, that is, being available on both Uber and Lyft’s networks at the same time. Lyft was ready-and-able to absorb unhappy Uber riders, because they were effectively using Uber’s drivers to accommodate them.

The timing could not have been worse: it was only a few months prior that Lyft appeared to be for sale and unable to find a buyer; it seemed that former-CEO Travis Kalanick was going to win one of his biggest gambles, turning down an offer to acquire Lyft in 2014 in exchange for 18% of Uber.

It proved to be Kalanick’s biggest mistake, at least from a business perspective: within weeks of the Uber scandal explosion Lyft raised $600 million, and a month later formed a partnership with Waymo, Google’s self-driving car company. Suddenly the best way to invest in the most promising self-driving technology was Lyft; unsurprisingly Lyft has since raised an additional $2.3 billion, including an investment from Google Capital.

Uber’s Competitive Context

The reason this context matters is that a proper analysis of Uber’s business is fundamentally different today that it was two years ago — or four years ago, when I wrote Why Uber Fights. That is when I made the argument that even though Uber’s two-sided network effects were relatively weak thanks to the lack of driver lock-in, the fact that ride-sharing was a commodity market meant its head start and brand would lead to slow-but-steady growth in marketshare, eventually starving Lyft due to an inability to raise funds based on increasingly inferior financial results.

I stand by that analysis: it is exactly what happened, and Uber came very close to knocking Lyft out. At the same time, it is also no longer applicable, because Lyft no longer has any problem raising money, while Uber appears to be having a hard time holding onto its market share (as an indirect indicator of Uber’s waning power with consumers, note Uber’s recent inability to defeat a cap on ride-sharing in New York, after doing just that three years ago). To that end, the prospect of Lyft being present in the market for the foreseeable future means Uber’s needs a new strategy than simply squeezing Lyft dry.

Welcome to bundles, Uber-style.

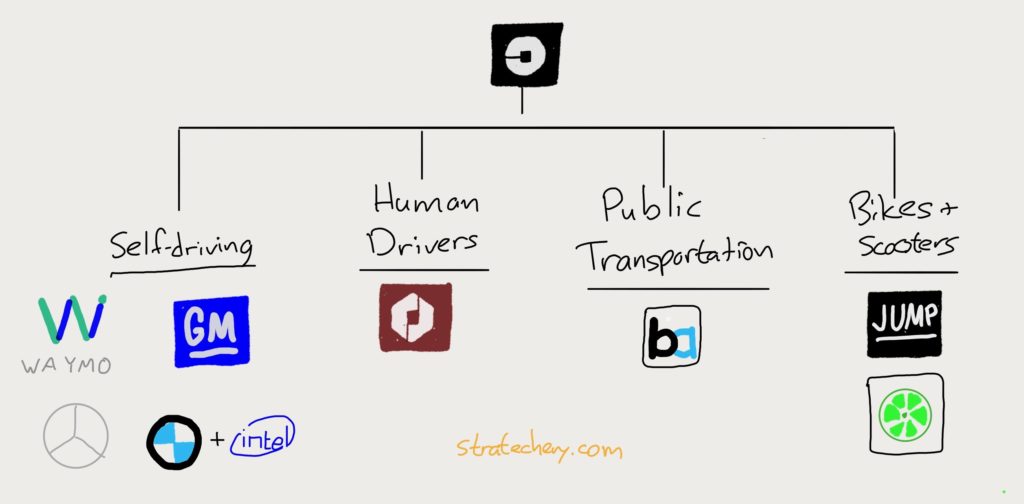

Uber’s Consumer Bundle: Transportation-as-a-Service

Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi laid out a new vision for the Uber app in an interview with Kara Swisher earlier this year at the Code Conference:

DK: We are thinking about alternative forms of transport. If you look at Jump, the dockless bicycle startup Uber acquired earlier this year, the average length of a trip at Jump is 2.6 miles. That is, 30 to 40 percent of our trips in San Francisco are 2.6 miles or less. Jump is much, much cheaper than taking an UberX. To some extent it’s like, “Hey, let’s cannibalize ourselves.” Let’s create a cheaper form of transportation from A to B, and for you to come to Uber, and Uber not just being about cars, and Uber not being about what the best solution for us is, but really being about the best solution for here.In case you had any question about how serious Khosrowshahi is about the concept, he told the Financial Times in an interview yesterday:

KS: So bikes, scooters?

DK: Bikes, perhaps scooters. I wanna get the bus network on. I wanna get the BART, or the Metro, etc., onto Uber. So, any way for you to get from point A to B.

KS: Wait, you wanna start your own BART? No.

DK: No, no, no. We’re not gonna go vertical. Just like Amazon sells third-party goods, we are going to also offer third-party transportation services. So, we wanna kinda be the Amazon for transportation, and we want to offer the BART as an alternative. There’s a company called Masabi that is connecting Metro, etc., into a payment system. So we want you to be able to say, “Should I take the BART? Should I take a bike? Should I take an Uber?” All of it to be real-time information, all of it to be optimized for you, and all of it to be done with the push of a button.

KS: So, any transportation?

DK: Any transportation, totally frictionless, real time.

During rush hour, it is very inefficient for a one-tonne hulk of metal to take one person 10 blocks…We’re able to shape behaviour in a way that’s a win for the user. It’s a win for the city. Short-term financially, maybe it’s not a win for us, but strategically long term we think that is exactly where we want to head…This is very much a bundle, and like any bundle, what makes the economics work in the long run is earning a larger total spend from consumers even if they spend less on any particular item. To that end, as Khosrowshahi notes, the real enemy is the car in the garage; to the extent Uber can replace that the greater its opportunity is.

We are willing to trade off short-term per-unit economics for long-term higher engagement…I’ve found in my career that engagement over the long term wins wars and sometimes it’s worth it to lose battles in order to win wars.

Moreover, the more that Uber can handle all of an end user’s transportation needs through the sort of complexity inherent in building such a service, the stickier Uber becomes for consumers. Granted, Lyft is promising to build the same thing, but Uber is a bit ahead and still has the bigger war chest, which may prove more helpful in a land grab as opposed to the current war of attrition. Moreover, Uber still has a significant geographic advantage over Lyft, which only just started expanding internationally, making it a better option for travelers.

Uber’s Driver Bundle: Uber Eats

Uber Eats, meanwhile, has the potential to be a very attractive business in its own right: Khosrowshahi said at Code Conference that the business has “a $6 billion bookings run rate, growing over 200 percent.” Uber takes 30% of that ($1.6 billion), as well as a $5 delivery fee from customers, out of which it pays drivers a pickup fee, drop-off fee, and per-mile rate (of which it keeps 25%); according to The Information, the service isn’t making money yet, but it is much more profitable than Uber’s ride-sharing business was at a similar scale.

Leaving aside the drivers for a moment, this is a classic aggregation play, where owning consumer demand gives Uber the ability to attract suppliers, increasing consumer demand in a virtuous cycle. Jason Droege, the Uber Vice President and Head of UberEverything, told Eater in an interview this past summer:

I think that we’re all here to service the consumer, right? And the eater. And I think eaters today want convenience, they want value, they want flexibility, and they want choice. And delivery offers all of those things. And restaurants choose to participate in delivery. And so if they don’t believe it’s valuable as a channel to connect to their consumers, or maybe new consumers, or reach new people with their brand, then that’s okay. We’re here to provide a conduit between the two. Not to tell them how to run their business.It certainly is an open question as to whether services like Uber Eats help or hurt established restaurants; this New Yorker article recounts a number of anecdotes about restauranteurs who are a bit fuzzy on exactly how much Uber Eats is costing them, much like Uber drivers that forget to account for the wear-and-tear on their cars. At the same time, Uber is creating entirely new opportunities for restaurants focused on delivery, just as it did for drivers that only wanted to work sometimes, or couldn’t find any other job at all, as well as companies to service them like HyreCar.

Moreover, Uber Eats has a leg-up in the space because of Uber itself: the latter can acquire customers from the former (both because of owned-and-operated advertising as well as reducing drop-off because Uber already has payment details), and all of those huge marketing and G&A expenses from building out teams in every city Uber operates is easily leveraged for Uber Eats. This of course applies to driver acquisition costs as well.

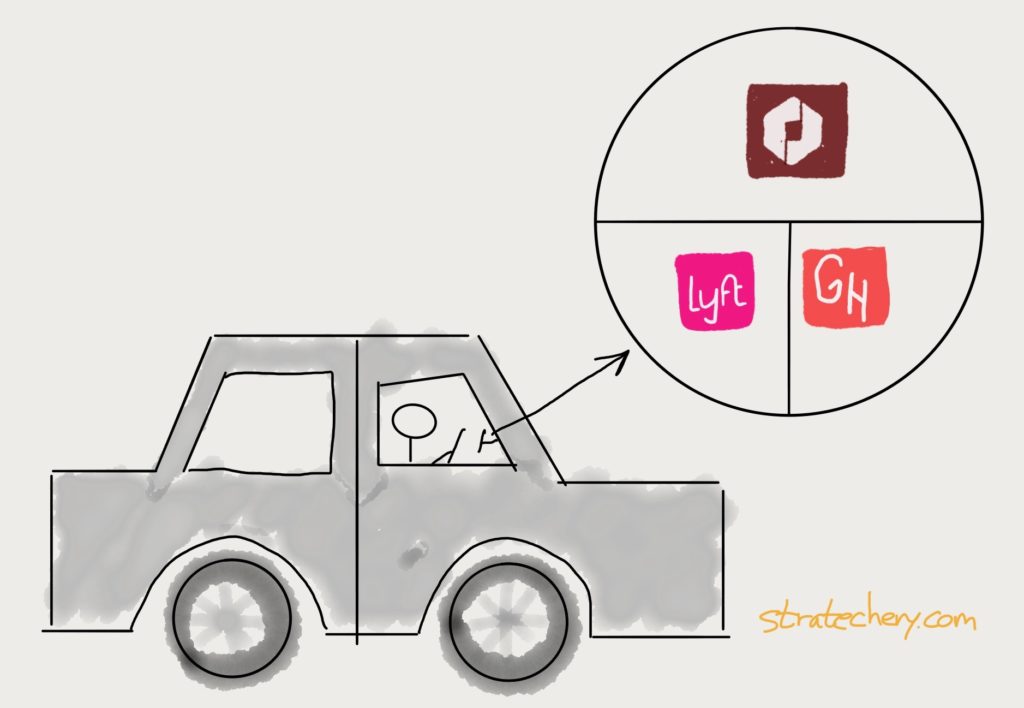

The biggest payoff, though, comes from effectively bundling opportunities for drivers. The problem for any standalone restaurant delivery app is that the vast majority of orders come at lunch and dinner, but the driver may wish to work at other times of the day as well. With Uber that is easy: just pick up riders (Uber drivers can drive for just Uber, just Uber Eats, or both). In other words, Uber has more and more ways to monopolize a driver’s time, to the driver’s benefit personally and Uber’s benefit competitively.

To be sure a GrubHub driver, to take one Uber Eats competitor at random, could also drive for Lyft (or Uber, for that matter), but that is where rewarding drivers for a certain number of rides in a given time period is particularly effective: because drivers can complete their “Quests” with Uber ride-sharing trips or Uber Eats trips, it often makes more sense to simply stick with Uber.

More broadly, the challenge Uber faces with drivers derives from the same fungibility that makes the service possible in the first place. To that end, the best way to approach the driver market is not to compete against this reality but to embrace it, and having multiple services that utilize the same driver pool accomplishes exactly that.

Self-Driving Cars: A Bundle as the Way Forward

Self-driving cars, meanwhile, remain Uber’s white whale. The company received a $500 million investment from Toyota yesterday, and will work to incorporate its technology into Toyota Sienna minivans.

This is definitely not the divesture of the unit that The Information says has been mooted; the unit has apparently cost Uber $2 billion over the last two years. Of course, as I noted above, that cost pales in comparison to the strategic impact of losing Google as a potential partner to Lyft.

Still, it is never too late to consider doing the right thing: I continue to believe that Uber’s investment in self-driving cars was a strategic mistake. Yes, its biggest cost is drivers, and a theoretical Google ride-sharing service could, were it at scale, completely undercut Uber, but that is the shallowest possible way to analyze how this market might have played out.

Keep in mind the point I just made about drivers: sure it sounds attractive to convert your most expensive supply input, which must be paid on a marginal basis and that you don’t control, into a fixed cost that you have exclusive rights to. That, though, means massively more capital expenditures for a business that is currently losing around a billion dollars a quarter. Worse, it means competing with Google in an area — machine learning — where the search giant has a massive advantage.

Moreover, in the long run it seems unlikely that Google would want to build up a vertical Uber competitor: it remains far more logical, both financially and in terms of Google’s historical margin profile, to license out their technology. To be sure, if Waymo’s technology were superior, they would have wholesale transfer pricing power, which Tren Griffin describes as:

The bargaining power of company A that supplies a unique product XYZ to Company B which may enable company A to take the profits of company B by increasing the wholesale price of XYZHere’s the thing though: Uber is better equipped than anyone else to deal with Waymo’s potential ability to extract margin for superior self-driving technology. After all, the company is already paying for driving technology — the technology just happens to be a human!

Of course that doesn’t mean Uber should settle for paying Waymo instead of drivers: the ride-sharing service remains the best possible way to go-to-market for everyone working on self-driving technology. To that end Uber should be willing to partner with anyone and everyone — and to share its technology with whoever wants it. In the long run Uber has market power thanks to its network, and it will best exploit that power to the extent it can engender competition amongst suppliers in the self-driving car space.

Moreover, it seems certain that whenever self-driving cars come along (and even Waymo is having trouble), they will not be suitable for all of the environments Uber operates in. That makes Uber uniquely suited to bundle self-driving car service with traditional Uber car service, as well as all of the other transportation services it plans to offer to consumers. This “bundle” will allow self-driving technology to come-to-market gradually when and where it makes sense, while still giving riders the confidence they can get from anywhere to anywhere.

To be fair, Khosrowshahi has signaled the desire to partner with multiple self-driving partners, including Google. I suspect, though, that will be hard to accomplish as long as Uber is pursuing its own exclusive technology. To that end Khosrowshahi should cut the cord with Uber’s self-driving program sooner rather than later, or perhaps even open-source it; the money savings are in fact the second most important potential benefit.

There was a certain satisfying simplicity to the brutality of Uber’s original strategy under Kalanick: be as aggressive as possible to establish an early lead, and then leverage Uber’s seemingly limitless ability to raise money to spend its competitors into submission. In the end, though, that same brutality did Kalanick in, and his strategy along with it.

That left Khosrowshahi with a much more complicated situation: not only did he need to fix Uber internally, he needed to create an entirely new strategy to win in a market that was fundamentally altered because of Uber’s crisis. The bundling of services for users, of opportunities for drivers, and ideally of technologies for self-driving makes sense as an alternative.

This strategy is, though, befitting the nature of the situation, considerably more complicated, and the commensurate chances of success — and ultimately, of profitability — a fair bit lower. In other words, Uber’s boardroom drama may be over, but the company remains perhaps the most compelling in tech.

4 comments:

Phentermine 37.5mg

Tramadol 100mg

Adderall 30mg

Xanax 2mg

Xanax 1mg

Ambien 10mg

Viagra 100mg

Generic Fioricet 40mg

Vallium 10mg

Ativan 2mg

Soma 350mg

Online Medication Shoppe

online pharmacy

medications

Weight loss

Pain relief

Sleep insomnia

Mens health

ANXIETY

ANTIARRHYTHMICS

MUSCLE RELAXANT

PAIN RELIEF

US Cheap Pharmacy

Phentermine

Tramadol

Adderall

Xanax

Ambien

Viagra

Generic Fioricet

Vallium

Ativan

Soma

Klonopin

Ultram

Adderall

Clonazepam

Lorazepam

Adipex

Just started driving for hyrecar. First rental and during the process needed support, you guys were amazing. Already had a issue getting vehicle registered with Uber. Reported the issue and got immediate resolution. You guys are so good at customer service you should consider providing consulting to other business!

Thank you for taking care of me.

Happy New Year!

This organization was framed for the individuals who consistently battle to observe to be excellent and solid, pet bed manufacturers for their canines or pets overall.

Sam works as a Manufacturing Head at Gtaimetal. Gtaimetal are very famous CNC milling parts suppliers & CNC Scooter Parts in the international market

Post a Comment