This concern is compounded by the evidence of false and mistaken measures the two have generated. Under these circumstances, advertisers and marketers have no choice but to create a countervailing force in order to keep some balance in reporting. JL

Lauren Johnson reports in AdWeek:

Despite their collective clout—or maybe because of—Facebook and Google’s walled gardens limit the amount of data and analytics that advertisers can access to track the performance of their campaigns, specifically when it comes to comparing ads to other digital platforms. More and more brands are taking a harder stance on the walled gardens that Facebook and Google have built around their metrics.

Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, a $1 billion U.S. advertiser, is fed up with playing by Facebook’s rules. As a result, the carmaker concocted its own set of measurement standards that combine video views with a layer of additional stats, prodded by what it sees as a lack of comparability for Facebook to other media it buys.

“We’ve come to the conclusion that we need to standardize our own view of the metrics,” explains Amy McNeil, head of digital media at FCA U.S. “We are collaborating with [our media agency] Universal McCann on the addition of time spent as an engagement qualifier, along with delivering on demo and in-view.” Such work piecing together custom metrics puts “a value on that platform, their reach, how successful we were in video completion,” she adds. “When we can prove out that it looks like any other buy that we’re doing, that’s when we increase our [budget]. Until we can get that third-party validation, our spend levels are what they are.”

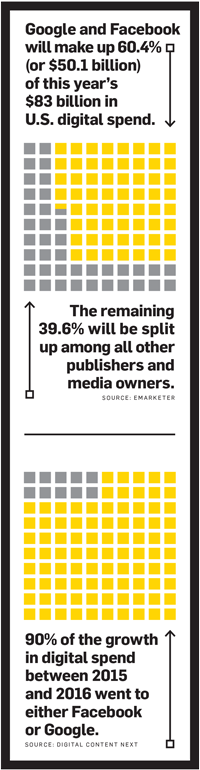

That can’t be good news for Facebook—or Google, which is facing similar pushback from marketers. Here’s why FCA and other marketers are so frustrated with this veritable duopoly. The two behemoths are poised to gobble up a staggering 60.4 percent—or roughly $50.1 billion—of this year’s $83 billion U.S. digital advertising market, with the remaining 39.6 percent split among all other publishers and platforms, per eMarketer. Moreover, a report from trade group Digital Content Next claims that 90 percent of the growth in digital spend between 2015 and 2016 went to one or the other.

Despite their collective clout—or maybe because of—Facebook and Google’s walled gardens limit the amount of data and analytics that advertisers can access to track the performance of their campaigns, specifically when it comes to comparing ads to other digital platforms. More and more brands are taking a harder stance on the walled gardens that Facebook and Google have built around their metrics. Procter & Gamble—the U.S.’ largest advertiser at $2.4 billion last year, per Kantar—has pledged to cut spend if the platforms don’t clean up their measurement act by the end of this year. “Adopt the minimum [Media Rating Council’s] standard and stop peddling your own version—it only creates confusion,” P&G CMO Marc Pritchard recently told attendees at the 4A’s Transformation Conference in Los Angeles, taking a direct jab at Facebook and Google. “Then we can focus on the hard work of analyzing effectiveness and making investment choices,” he said, according to a transcript of his presentation.

The root of the problem

As the two giants of digital, advertisers have long leaned on Facebook and Google to make sense of their campaign data and relay back what’s working and what isn’t. But as more money moves from traditional media to digital, a growing number of marketers are beginning to question what exactly that data entails and are pushing for unified metrics that align with all other digital media.

“They are a duopoly that has the market power to act like a monopolist,” notes Mike Mothner, CEO of Wpromote. “The fact is, advertising on these platforms is so important that it overcomes any shortcoming or lack of comfort that we have.”

When asked if Facebook—which attracted nearly $27 billion in ad revenue in 2016—takes measurement seriously, conventional wisdom among digital agency execs is that CEO Mark Zuckerberg would rather concentrate on getting drones in the sky to distribute Facebook’s signal globally than focus on nitty-gritty measurement issues closer to the ground.

And when it comes to Google, some agency execs would rather avoid that fight, given the Mountain View, Calif.-based digital giant’s control over search advertising and the troves of data that underpin its eMarketer-estimated $28.5 billion U.S. search business this year.

Chiefly, the measurement concerns hinge on watchdog Media Rating Council’s 3-year-old viewability standard, which charges advertisers when 50 percent of a display ad is in view for one second—two seconds for video spots. The metric has become the de facto way publishers transact digital media, but platforms like Facebook and Google’s YouTube are notoriously reluctant to give out too much data to advertisers for fear of, some industry players allege, losing a competitive advantage and advertising dollars.

Today, marketers are demanding more. “There is a lack of confidence in whether or not my digital media is performing for my business KPIs,” explains Jeff Liang, chief digital officer at Assembly. “I think these two companies want to keep it closed as long as possible for their own benefit, and that’s what’s making things really tough.”

While both Facebook and YouTube do employ third-party measurement firms, including Moat, Integral Ad Science and DoubleVerify to track viewability, neither company has undergone a full-blown audit by the MRC to be accredited as a platform, a process that requires a thorough vetting to examine the ins and outs of how data is collected and reported.

“It’s sort of a basic building block,” notes Joe Barone, GroupM’s managing partner of digital advertising operations. “We need to be able to measure whether or not it was seen, so that we can measure and value everything else about it.”

Viewability is undoubtedly a buzzy topic, but it’s only the tip of the iceberg of advertisers’ qualms with the tech giants. In a series of interviews with more than 20 companies for this story, marketers cited different variations of broader gripes with the platforms’ reach, frequency and attribution data as well as lingering concerns about brand safety in light of major marketers recently pulling YouTube ads that ran alongside objectionable content.

Planting the seeds

Tensions between the two sides reached a boiling point in September when Facebook revealed it had been reporting inflated video metrics to agencies that tracked the average amount of time people spent watching clips—although it was quick to note the mistake did not affect billing. Since then, Facebook has disclosed a handful of other errors while rolling out new measurement tools. The revelations caused a slew of marketers, including card-carrying members of the Association of National Advertisers, to ask for both Google and Facebook to pull aside the curtains of secrecy that veiled their ad business to give marketers a complete look at how their campaigns perform.

“What we hear from our members is that they can’t integrate the media with other media to create a more holistic plan because they can’t transport data,” says Bill Duggan, group evp at the ANA.

In February, both companies agreed to undergo audits from the MRC to become accredited for third-party viewability measurement this year, which the MRC says are on track to begin during the second quarter.

There are some potential twists in measuring walled gardens like Facebook and Google, though. While auditors (also called CPA firms) are required to analyze all parts of a business’ technology, they also have to work a bit around each company’s proprietary code to keep it safe from fraudsters and other perpetrators.

“Everything is fair game as part of the audit if it contributes to what we’re auditing,” says David Gunzerath, svp and associate director at the MRC. “That said, we recognize the importance of these companies’ ability to maintain confidentiality around the proprietary nature of certain techniques, so something like a digital measurement company’s filtration techniques … if that information gets in the public domain, the bad guys will know how to work around it, and that’s bad for everybody.”

Opening up Google

As if the data and metrics troubles aren’t confusing enough, Facebook and Google approach them differently.

Keeping track of Google’s measurement work is particularly tricky because of its enormous breadth of advertising across search, display and video. While not officially accredited, YouTube says its stats prove that the MRC’s definition works.

“There’s data behind it, and it shows that it increases value when you’re in the cycle of awareness or purchase intent,” explains Google’s Babak Pahlavan, senior director of product management, analytics solutions and measurement. “One of the good things about it is that it covers both viewability and audibility—what we’re seeing is in particular [with] brand advertisers [is that] their campaigns are both viewable and audible.”

According to Pahlavan, campaigns that take viewability and audibility into account for measurement perform 2.9 times better than campaigns that only use one of the criteria. YouTube reports that 93 percent of its inventory meets the MRC’s definition of being viewable while 95 percent is deemed audible.

Excluding the current pending audit, Google has collected 30 MRC accreditations since 2006, including its ad-serving platform DoubleClick and AdWords, which powers search ads. Within video, mobile and desktop clips that run in Google’s DoubleClick Campaign Manager are accredited and meet the MRC’s standards, pointing to how complex and granular digital measurement is.

“Depending on the scope, I think [it takes anywhere] from six to nine months, sometimes 12 months to get one metric accredited—it’s not something that we started doing a few months ago,” Pahlavan says. “In order to get accredited, there is a very diligent process, which means that you have to have staffing in place in terms of analytics, engineers and product people to go through it—it takes quite an amount of investments from outside to do this.”

Still, marketers say that Google sits on troves of data—particularly within search—it’s not giving them access to. For example, Google can help hotel brands fine-tune the search terms they buy ads against, but they aren’t privy to the full extent of Google’s data on how people search for travel information. Google has a program called Google Analytics 360 to help big brands pull together some of that information—but it’s only available to Google’s biggest enterprise clients (such as L’Oréal). Brands have to be willing to trust Google to manage the data.

“You can find ways for Google to share that with you, if you start to use their premium products,” explains Baylen Springer, vp of marketing analytics at R2C Group. “That’s really interesting to us, but it requires some additional investment to get that ability.” To him, investment in measurement shouldn’t cost extra, given how much information Google has at its fingertips.

Measuring Facebook

Facebook’s definition is a bit murkier because of how people scroll through newsfeeds. By default, marketers are charged the second that an ad appears in a newsfeed, regardless of how long it is viewed. Facebook cites research from Fors Marsh Group to back up its claim: People exposed to mobile promos for as little as .25 seconds reported an increase in ad recall.

Later this year, Facebook plans to roll out three options for buying video ads. One option will use the MRC’s definition requiring that 50 percent of an ad is in view for two seconds while a stricter version allows brands to only pay for videos that are watched for up to 10 seconds. Finally, in response to lingering concerns from brands about paying for autoplay videos that are watched without sound, marketers can choose to only fork over payment for clips in which sound was turned on.

After Facebook acquired ad-tech platform Atlas from Microsoft in 2013, Atlas remained accredited with the MRC until last year when the company started shutting the ad server down to focus on measurement. And while the upcoming viewability audit is set to happen, currently Facebook and Instagram are not MRC accredited.

According to Brad Smallwood, Facebook’s vp of measurement and insight, viewability is only one measurement factor that brands should focus on. Stats like time spent, the size of the ad, sound and the percentage of the screen that an ad was seen in are also vital measurement tools he promotes.

“The important part of this is giving marketers enough information so that they can tie [it] to the ultimate business outcome that they have, whether that be recall, awareness, online sales, in-store sales,” Smallwood says. “You’ve got to make sure that the metrics are accurate in order to make sure that they’re tying to their ultimate business outcomes.”

To that end, the team formerly working on Atlas is now involved in a new initiative called advanced measurement that brands can use to track reach and attribution across Facebook, Instagram and Atlas’ publisher sites.

That said, as with Google Analytics 360, the problem is those stats are provided by Facebook—a fact that leaves some marketers wary (especially in light of the recent video metrics revelations). It’s also unclear how granular the data will be in comparing Facebook to Google, Twitter, Snapchat or more importantly, television, where big brands typically spend the most. The white-hot pursuit of cord-cutters also factors into digital companies’ renewed obsession with performance stats—there’s a mountain of ad dollars at stake that could instead go to Twitter, Snapchat, Pinterest and other challengers.

“I almost feel like if the smaller players in the market could work together to create a more open consumer data access model, they might be able to challenge the dominance of Facebook and Google,” suggests Treasure Data CMO Kiyoto Tamura.

Brandon Rhoten, Wendy’s vp and head of advertising, media, digital and social media, notes that he and his team don’t even bother trying to use Google and Facebook’s dashboards, instead relying heavily on measurement player Nielsen to extract insights across all media to decide where to buy ads. Referring to how Facebook measures all its properties (including Instagram and Messenger) with similar metrics, Rhoten asks: “If one company that has all the same leadership can’t figure out [how] to truthfully treat their metrics in a way that makes sense, how the hell are you going to compare Facebook and YouTube? And then, how are you going to compare that with television? That’s a big ask … It is complicated and everyone has a different opinion.”

Digging into the platforms

Yes, it is complicated. And ad-tech firms are getting wise to the needs marketers have. Kochava, Nanigans and Adobe are each working to give advertisers a bit more data about their Facebook campaigns, such as examining how creative impacts attribution, according to one source.

“What we’re finding more and more are the tools we’re going to be using to help us measure the success in a platform are not within the platform at all—we’re using the [platforms’] data, but we’re not using it in the format that they provide,” Rhoten says. “As more brands are becoming channel-agnostic, we need those third parties because they can aggregate the data and actually pull it all together.”

Lou Paskalis, svp of enterprise media planning, investment and measurement executive at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, explains the measurement woes another way. When he runs a campaign targeting adventure travelers, Facebook and Google’s sophisticated targeting tools can zero in on prospects who identify as adventure travelers. But he’s not able to take those insights to possibly retarget folks with another campaign on, say, Condé Nast Traveler’s website.

“Every platform is nuanced, and the rules are changing frequently, but at the end of the day those insights are generally not portable,” says Paskalis. “The reality is that the advertising model is moving toward a CRM-like model where we’re actually orchestrating experiences on paid and in owned environments from the same central logic—if I can’t get signal from those two platforms, I’m being denied a fairly big amount of signal that’s going to handicap me in creating more relevant experiences.”

The lack of data is causing media agencies like New York-based Noble People to get creative and go around the platforms when setting up targeting parameters. “The way that you get around those things is to be very tricky with how you set up campaigns—that gets very tedious,” says Noble People’s director of performance Paul Vikan. “You cut it up as many ways as you possibly can [for targeting purposes] so that when you export that data, you [own] it. But we’re never going to see very specific data on specific targeting in massive campaigns if you don’t set it up that way.”

Safety check

Ownership and portability of insights from Google and Facebook isn’t the only issue that’s come to a head recently. There’s brand safety, which became a major concern when dozens of big-name brands including AT&T and Johnson & Johnson immediately froze YouTube budgets after published reports pointed out incidents of ads running alongside racist and terrorist videos, often the result of Google’s automated ad-targeting software. All told, investment firm Nomura Instinet estimates that the brouhaha could cost Google $750 million in lost ad revenue.

“Brand safety and programmatic isn’t really a new topic,” explains Andrew Casale, president and CEO at Index Exchange. “Perhaps because of all the other amplified issues—fake news, the election, Breitbart—it just feels like the perfect storm has occurred.”

“Brand safety can trump performance,” Wpromote’s Mothner adds. “We are having more serious conversations about that than we are on slight misreporting on the measurement side—it’s the real deal.”

One major ad agency exec who spoke on the condition of anonymity suggested that YouTube’s fiasco is another way that brands are seeking to gain leverage over the platforms. “Calling YouTube or Facebook unsafe is unfair because the numbers don’t prove that to be true,” the exec says. “If something is unsafe, it would mean that it’s an 80/20 split, with 80 percent good, 20 percent bad [content]—it’s [actually closer to] 99.9/.01. Most people are not searching for ISIS, they’re searching for cat videos and the vast majority of people are getting a message in an environment that they’re comfortable with.”

Still, it’s an issue that’s grabbing the attention of CEOs and execs that are putting pressure on Google to clean up its platforms before they invest more money. “I think it’s definitely a reaction to the market, and I don’t know if Google was prepared for the very loud and angry reaction they got from advertisers and agencies,” says Mitch Weinstein, svp and director of ad operations at IPG Mediabrands.

YouTube has since updated the policies for creators that participate in its ad-partner programs, requiring channels to amass 10,000 lifetime views before clips can make money. Measurement firms Integral Ad Science, DoubleVerify and comScore will also begin vetting videos to steer advertisers away from questionable content.

“If these verification companies build that into their reporting where they can tell us violations about ads running adjacent to really bad content, that’s something that will be really important for us and we’ll utilize on a regular basis,” Weinstein adds.

Waning trust

Meanwhile, the drip, drip, drip of measurement corrections from Facebook since last fall irks marketers who feel like they’ve been dragged along by the platform’s constantly changing algorithms and policies for years, says Assembly exec Liang.

“We should know based on those types of lessons that we cannot actually trust any sellers who are creating their own metrics,” Liang says.

Since November, Facebook has admitted to additional errors with its fast-loading, mobile-minded Instant Articles, organic daily reach on its pages and additional video errors, all of which has led some marketers to approach the social giant with a larger measure of caution.

“I had my monthly email to the agency of, ‘Facebook measurement challenges,’ and [updated] to Volume 2, Volume 3 pretty much every month in the fall,” notes Ali Plonchak, managing director of digital strategy and integration at CrossMedia. “After seeing a pattern, it was one of the things that started to also alert clients that Google and Facebook cannot be measuring themselves all the time.”

The pattern of frequently disclosing inaccurate metrics on a one-off basis is also worrisome to marketers. “At this point, I think they need to pause and think about how they report performance,” says Rachel Allen, vp and group media director at MullenLowe Mediahub, which handles media buying for JetBlue.

Indeed, Wendy’s Rhoten argues that part of the problem is Facebook’s rapid rollout of products, which have particularly leaned on autoplay videos that play as people scroll through newsfeeds and inflate numbers around how many people watch a clip. (Expect even more developments at its F8 conference this week.) “It’s a bit of a challenge to deliver metrics against all those new products, and they probably have a more complicated product to report on than Google does,” he says. “Facebook is primarily concerned with the experience of its users, and the secondary component is an advertising platform.”

Or, as Jason Kint, CEO of Digital Content Next, puts it: “The bigger uncertainty is what do we not really know? What hasn’t been posted?”

What we do know is Facebook and Google stand to lose a lot more money if they don’t show enough change in the eyes of marketers.

0 comments:

Post a Comment