Postings for software development jobs are down 30% since February 2020. Industry layoffs have continued this year with tech companies shedding 137,000 jobs since January. (And) tech firms have become laser focused on revenue-generating products and services, pulled back on entry-level hires, cut recruiting teams and jettisoned projects and jobs in areas that weren’t huge moneymakers, including virtual reality and devices. It’s a reset in an industry that is readjusting its labor needs and pushing some workers out. (But) AI engineers are being offered two- to four-times the salary of a regular engineer. “That’s an extreme investment in an unknown technology. They cannot afford to invest in other talent because of that.”

Finding a job in tech by applying online was fruitless, so Glenn Kugelman resorted to another tactic: It involved paper and tape.

Kugelman, let go from an online-marketing role at eBay, blanketed Manhattan streetlight poles with 150 fliers over nearly three months this spring. “RECENTLY LAID OFF,” they blared. “LOOKING FOR A NEW JOB.” The 30-year-old posted them outside the offices of Google, Facebook and other tech companies, hoping hiring managers would spot them among the “lost cat” signs. A QR code on the flier sent people to his LinkedIn profile.

“I thought that would make me stand out,” he says. “The job market now is definitely harder than it was a few years ago.”

Once heavily wooed and fought over by companies, tech talent is now wrestling for scarcer positions. The stark reversal of fortunes for a group long in the driver’s seat signals more than temporary discomfort. It’s a reset in an industry that is fundamentally readjusting its labor needs and pushing some workers out.

Postings for software development jobs are down more than 30% since February 2020, according to Indeed.com. Industry layoffs have continued this year with tech companies shedding around 137,000 jobs since January, according to Layoffs.fyi. Many tech workers, too young to have endured the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s, now face for the first time what it’s like to hustle to find work.

Company strategies are also shifting. Instead of growth at all costs and investment in moonshot projects, tech firms have become laser focused on revenue-generating products and services. They have pulled back on entry-level hires, cut recruiting teams and jettisoned projects and jobs in areas that weren’t huge moneymakers, including virtual reality and devices.

At the same time, they started putting enormous resources into AI. The release of ChatGPT in late 2022 offered a glimpse into generative AI’s ability to create humanlike content and potentially transform industries. It ignited a frenzy of investment and a race to build the most advanced AI systems. Workers with expertise in the field are among the few strong categories. “I’ve been doing this for a while. I kind of know the boom-bust cycle,” says Chris Volz, 47, an engineering manager living in Oakland, Calif., who has been working in tech since the late 1990s and was laid off in August 2023 from a real-estate technology company. “This time felt very, very different.”

For most of his prior jobs, Volz was either contacted by a recruiter or landed a role through a referral. This time, he discovered that virtually everyone in his network had also been laid off, and he had to blast his résumé out for the first time in his career. “Contacts dried up,” he says. “I applied to, I want to say, about 120 different positions, and I got three call backs.”

He worried about his mortgage payments. He finally landed a job in the spring, but it required him to take a 5% pay cut. During the pandemic, as consumers shifted much of their lives and spending online, tech companies went on hiring sprees and took on far too many workers. Recruiters enticed prospective employees with generous compensation packages, promises of perpetual flexibility, lavish off sites and even a wellness ranch. The fight for talent was so fierce that companies hoarded workers to keep them from their competitors, and some employees say they were effectively hired to do nothing.

A downturn quickly followed, as higher inflation and interest rates cooled the economy. Some of the largest tech employers, some of which had never done large-scale layoffs, started cutting tens of thousands of jobs.

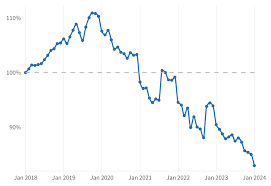

The payroll services company ADP started tracking employment for software developers among its customers in January 2018, observing a steady climb until it hit a peak in October 2019.

The surge of hiring during the pandemic slowed the overall downward trend but didn’t reverse it, according to Nela Richardson, head of ADP Research. One of the causes is the natural trajectory of an industry grounded in innovation. “You’re not breaking as much new ground in terms of the digital space as earlier time periods,” she says, adding that increasingly, “There’s a tech solution instead of just always a person solution.”

Some job seekers say they no longer feel wined-and-dined. One former product manager in San Francisco, who was laid off from Meta Platforms, was driving this spring to an interview about an hour away when he received an email from the company telling him he would be expected to complete a three-part writing test upon his arrival. When he got to the office, no one was there except a person working the front desk. His interviewers showed up about three hours later but just told him to finish up the writing test and didn’t actually interview him.

The trend of ballooning salaries and advanced titles that don’t match experience has reversed, according to Kaitlyn Knopp, CEO of the compensation-planning startup Pequity. “We see that the levels are getting reset,” she says. “People are more appropriately matching their experience and scope.” Wage growth has been mostly stagnant in 2024, according to data from Pequity, which companies use to develop pay ranges and run compensation cycles. Wages have increased by an average of just 0.95% compared with last year. Equity grants for entry-level roles with midcap software as a service companies have declined by 55% on average since 2019, Pequity found.

Companies now seek a far broader set of skills in their engineers. To do more with less, they need team members who possess soft skills, collaboration abilities and a working knowledge of where the company needs to go with its AI strategy, says Ryan Sutton, executive director of the technology practice group with staffing firm Robert Half. “They want to see people that are more versatile.”

Some tech workers have started trying to broaden their skills, signing up for AI boot camps or other classes. Michael Moore, a software engineer in Atlanta who was laid off in January from a web-and-app development company, decided to enroll in an online college after his seven-month job hunt went nowhere. Moore, who learned how to code by taking online classes, says not having a college degree didn’t stop him from finding work six years ago.

Now, with more competition from workers who were laid off as well as those who are entering the workforce for the first time, he says he is hoping to show potential employers that he is working toward a degree. He also might take an AI class if the school offers it.

The 40-year-old says he gets about two to three interviews for every 100 jobs he applies for, adding, “It’s not a good ratio.”

Struggling at entry level

Tech internships once paid salaries that would be equivalent to six figures a year and often led to full-time jobs, says Jason Greenberg, an associate professor of management at Cornell University. More recently, companies have scaled back the number of internships they offer and are posting fewer entry-level jobs. “This is not 2012 anymore. It’s not the bull market for college graduates,” says Greenberg.

Myron Lucan, a 31-year-old in Dallas, recently went to coding school to transition from his Air Force career to a job in the tech industry. Since graduating in May, all the entry-level job listings he sees require a couple of years of experience. He thinks if he lands an interview, he can explain how his skills working with the computer systems of planes can be transferred to a job building databases for companies. But after applying for nearly two months, he hasn’t landed even one interview. “I am hopeful of getting a job, I know that I can,” he says. “It just really sucks waiting for someone to see me.”

Some nontechnical workers in the industry, including marketing, human resources and recruiters, have been laid off multiple times.

James Arnold spent the past 18 years working as a recruiter in tech and has been laid off twice in less than two years. During the pandemic, he was working as a talent sourcer for Meta, bringing on new hires at a rapid clip. He was laid off in November 2022 and then spent almost a year job hunting before taking a role outside the industry. When a new opportunity came up with an electric-vehicle company at the start of this year, he felt so nervous about it not panning out that he hung on to his other job for several months and secretly worked for both companies at the same time. He finally gave notice at the first job, only to be laid off by the EV startup a month later.

“I had two jobs and now I’ve got no jobs and I probably could have at least had one job,” he says.

Arnold says most of the jobs he’s applying for are paying a third less than what they used to. What irks him is that tech companies have rebounded financially but some of them are relying on more consultants and are outsourcing roles. “Covid proved remote works, and now it’s opened up the job market for globalization in that sense,” he says. One industry bright spot: People who have worked on the large language models that power products such as ChatGPT can easily find jobs and make well over $1 million a year.

Knopp, the CEO of Pequity, says AI engineers are being offered two- to four-times the salary of a regular engineer. “That’s an extreme investment of an unknown technology,” she says. “They cannot afford to invest in other talent because of that.”

Companies outside the tech industry are also adding AI talent. “Five years ago we did not have a board saying to a CEO where’s our AI strategy? What are we doing for AI?” says Martha Heller, who has worked in executive search for decades. If the CIO only has superficial knowledge, she added, “that board will not have a great experience.”

Kugelman, meanwhile, hung his last flier in May. He ended up taking a six-month merchandising contract gig with a tech company—after a recruiter found him on LinkedIn. He hopes the work turns into a full-time job.

0 comments:

Post a Comment