Venture capitalists have become more demanding about startups hitting their growth projections - or suffering the consequences.

SPAC, aka, 'blank check' startups were intended to meet investor demand for more small, innovative companies, but that demand came mostly from inexperienced investors. And the SPAC startups used 'optimistic' projections - eg unrealistic or even unattainable - to sell shares. The result has been entirely predictable, underperformance. The question is why anyone ever thought a blank check was would lead to a positive investment return. JL

Heather Somerville and Eliot Brown report in the Wall Street Journal:

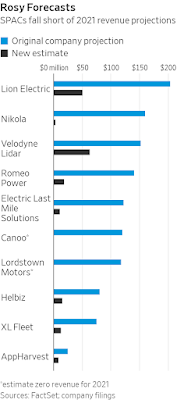

Half of all startups with less than $10 million of annual revenue that went public last year through a special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC), failed to meet the 2021 revenue or earnings targets they provided. Critics of SPACs say the loosely regulated going-public process allows startups to attract investors with bullish financial projections, despite having little or no revenue in their history. Some of the companies’ projections were “beginning to get outside the realm of feasible outcomes." A 2021 working paper reported high-growth revenue projections are likely to be “misleading to uninformed investors.” Serious investors have become demanding that companies deliver on promises for growth.A startup battery maker that wooed investors with rapid growth forecasts said it would miss its revenue target by as much as 89%. A scooter rental app is expected to bring in less than 20% of what it projected this year. An electric bus company that planned to boost revenue faster than any U.S. startup ever told investors to disregard its projections.

Dozens of startups that went public in a pandemic-fueled stock market frenzy are missing the projections they used to win over investors, many by substantial margins and just a few months after making those forecasts.

Nearly half of all startups with less than $10 million of annual revenue that went public last year through a special-purpose acquisition company, known as SPAC, have failed or are expected to fail to meet the 2021 revenue or earnings targets they provided to investors, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis.

The underperformance of these nascent companies—most of them tech startups—bolsters one of the biggest concerns many investors and others raised about the SPAC boom of the past two years. Critics of SPACs say the loosely regulated going-public process allows startups to attract investors with bullish financial projections, despite having little or no revenue in their history.

In November, eight months after electric bus and van maker Arrival SA’s public listing through a SPAC merger, Chief Executive Denis Sverdlov offered an update on an earnings call with investors. “We withdraw our long-term forecasts,” he said, adding that the company was putting forward “a more conservative view.”

It was a different tone from the pitch the company gave investors when it went public in March: Its revenue would grow from zero to $14 billion in just three years. It was a stunningly rapid pace—five years faster than Alphabet Inc.’s Google, the fastest U.S. startup ever to reach that level of revenue—particularly given Arrival hadn’t yet produced any vehicles.

The company declined to comment for this article. Its stock is down roughly 85% since listing.

Investors and academics have criticized speculative companies’ use of projections, saying they are used to create buzz and attract investors. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has indicated it is considering new limits on the practice and some federal lawmakers have advanced bills to curtail it. While regulations around traditional initial public offerings strongly discourage companies from making forecasts about future performance, companies that list publicly by merging with SPACs—which are sometimes called blank-check companies—have freely used forecasts, often presenting investors with charts showing enormous growth.

“The practice was perhaps being abused,” said Amy Lynch, a former SEC regulator who now advises investors on regulatory issues. She said some of the companies’ projections were “beginning to get outside the realm of feasible outcomes.

The Journal’s analysis covered the 63 companies that went public through a SPAC deal last year and had less than $10 million in trailing sales at the time of their listing. Of those 63, at least 30 didn’t meet their projections, according to the Journal’s analysis of data provided by Jay Ritter, a University of Florida professor who studies public listings, and from FactSet. A total of 199 SPAC deals were completed last year.

The revenue cutoff was designed to capture companies with no or very little commercial production. The Journal compared the companies’ initial projections with either analysts’ estimates from FactSet, updated company forecasts or earnings reports.

The companies in the Journal’s analysis that are poised to miss their 2021 revenue projections on average fell short by 53%. Companies that are behind on their earnings projections have estimated losses that are on average about 40% greater than what they projected at the time of their SPAC deal.

Proponents of the SPAC process say projections give stock market investors the ability to bet on startups by gauging their future potential, offering the opportunity for huge returns that are generally confined to investors who can access the private markets. Without giving projections, it would be extremely difficult for many early-stage startups to go public, because they don’t have a track record yet.

Some startups have followed through. Battery company Solid Power Inc., indoor farming startup Local Bounti Corp. and healthcare software firm Pear Therapeutics Inc. are each expected by analysts to meet or exceed their 2021 revenue projections; each company has revenue of around $4 million or less.

Professors who examined the issue found a correlation between ambitious forecasts and poor stock performance. Michael Dambra, an associate professor of accounting at University at Buffalo, and two co-authors looked at SPACs from 2010 through 2020 and concluded in a 2021 working paper that high-growth revenue projections are likely to be “overly optimistic and misleading to uninformed investors.”

“The more aggressive your revenue is, the more likely you are to underperform,” Mr. Dambra said in an interview.

One Silicon Valley battery maker faced skepticism when it announced a SPAC deal a year ago. Enovix Corp. had been around for 14 years and had yet to make a commercial sale of its product.

“We have got to build the company and hit our numbers,” CEO Harrold Rust told The Wall Street Journal a year ago.

Enovix is expected by analysts to miss its numbers. According to analysts’ estimates, its 2021 losses before accounting for costs such as interest and depreciation—known as Ebitda—are almost double what the company had previously projected to investors. A spokeswoman declined to comment.

Another battery manufacturer, Romeo Power Inc., in November told investors it will miss its 2021 revenue projection—$140 million—by as much as 89%. The company cautioned investors in a January filing of “substantial doubt” around its ability to continue without additional funding. Two of its customers have struck deals with another battery maker, and its stock is down more than 90% from its public listing.

Romeo said management is working on a solution, but couldn’t promise that “our plans will be successfully implemented or that we will be able to curtail our losses.” The company didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Expectations are also dim for Helbiz Inc., which operates apps to rent electric bikes and scooters, stream live sports and get food delivered. Analysts estimate the company will make less than a fifth of the revenue it had projected for 2021. It had also told investors to expect a profit on an Ebitda basis, but instead is expected by analysts to lose about $41 million by the same measure. A company spokesman declined to comment.

The stock tumble of many of these startups shows how serious investors have become about demanding that companies deliver on their promises for growth. Hedge fund Morgan Creek Capital Management has an exchange-traded fund that tracks SPACs and the startups that merge with them; it is down more than 49% from a year ago, according to FactSet.

“It has been a really bad 12 months,” said Chief Executive Mark Yusko. “Expectations are down, valuations are down.”

The average stock price for the 63 companies in the Journal’s study is roughly $5. Companies that use SPAC’s to go public have an initial stock price of $10.

Companies missing their numbers are in a tricky spot, said venture capitalists. They must either slow their spending, which would stunt their growth and make it more difficult to meet projections. Or they could raise more capital, which will likely be challenging, given their low stock prices, and lenders are less likely to provide debt to companies with limited income, venture capitalists said.

Enrique Abeyta, editor at Empire Financial Research, which gives investment guidance, said he expects half of the companies that went public with a SPAC last year will be out of business or delisted within five years. He is looking for opportunities in the market to short their stock.

“I feel like we are in a position right now in the world where SPAC is a four-letter curse word,” said Mr. Abeyta.

The SEC last year signaled new rules were coming when it added SPACs to its regulatory agenda, although no details were provided. SEC chairman Gary Gensler has warned against “misleading hype” in the sector, while the agency’s former general counsel has said companies face greater legal risk for financial projections than is commonly believed.

John Coates, who served as SEC general counsel and worked on SPAC regulation before he left the agency last fall, said he began taking a closer look at the projections after companies with little or no revenue began publicizing projections of revenue five or six years in the future.

“Even mature, well-run companies are cautious about going out five years,” Mr. Coates said. “I don’t know why a brand new company that’s never sold anything would feel comfortable about that.”

No comments:

Post a Comment