There are more than enough of them to fill any ostensible gap between supply and demand. What they need is encouragement, support, some training - and managerial imagination. JL

Byron Reese reports in Singularity Hub:

For 200 years, with the exception of the Great Depression, unemployment in the US has been between 2% and 13%. Europe’s range is a bit wider. If I took 200 years of unemployment rates, and asked you to find where the assembly line took over manufacturing, or where steam power replaced animal power, you wouldn’t be able to find those spots. Every fifty years, we lose half of all jobs, and this has been since 1800. The great skill is to be able to learn new things; that is our singular ability as a species. The question is, “Can everyone do a job just a little harder than the job they have today?”

One of the most contentious debates in technology is around the question of automation and jobs. At issue is whether advances in automation, specifically with regards to artificial intelligence and robotics, will spell trouble for today’s workers. This debate is played out in the media daily, and passions run deep on both sides of the issue. In the past, however, automation has created jobs and increased real wages.

A widespread concern with the current scenario is that the workers most likely to be displaced by technology lack the skills needed to do the new jobs that same technology will create.

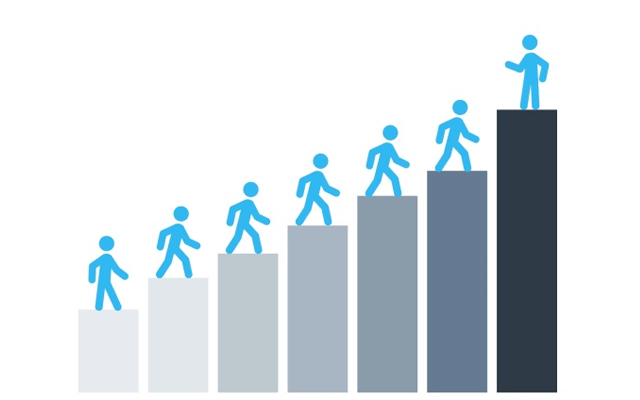

Let’s look at this concern in detail. Those who fear automation will hurt workers start by pointing out that there is a wide range of jobs, from low-pay, low-skill to high-pay, high-skill ones. This can be represented as follows:

They then point out that technology primarily creates high-paying jobs, like geneticists, as shown in the diagram below.

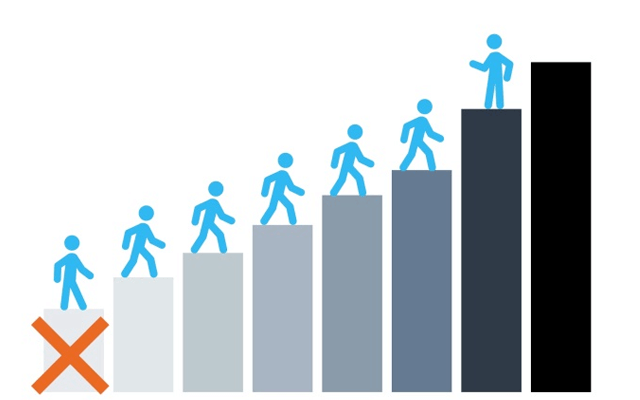

Meanwhile, technology destroys low-wage, low-skill jobs like those in fast food restaurants, as shown below:

Then, those who are worried about this dynamic often pose the question, “Do you really think a fast-food worker is going to become a geneticist?”

They worry that we are about to face a huge amount of systemic permanent unemployment, as the unskilled displaced workers are ill-equipped to do the jobs of tomorrow.

It is important to note that both sides of the debate are in agreement at this point. Unquestionably, technology destroys low-skilled, low-paying jobs while creating high-skilled, high-paying ones.

So, is that the end of the story? As a society are we destined to bifurcate into two groups, those who have training and earn high salaries in the new jobs, and those with less training who see their jobs vanishing to machines? Is this latter group forever locked out of economic plenty because they lack training?

No.

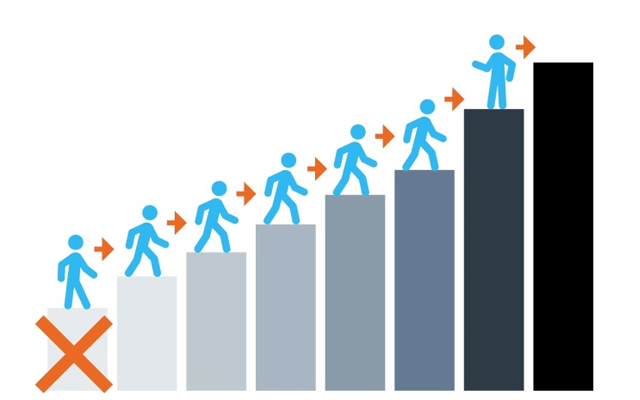

The question, “Can a fast food worker become a geneticist?” is where the error comes in. Fast food workers don’t become geneticists. What happens is that a college biology professor becomes a geneticist. Then a high-school biology teacher gets the college job. Then the substitute teacher gets hired on full-time to fill the high school teaching job. All the way down.

The question is not whether those in the lowest-skilled jobs can do the high-skilled work. Instead the question is, “Can everyone do a job just a little harder than the job they have today?” If so, and I believe very deeply that this is the case, then every time technology creates a new job “at the top,” everyone gets a promotion.

This isn’t just an academic theory—it’s 200 years of economic history in the west. For 200 years, with the exception of the Great Depression, unemployment in the US has been between 2 percent and 13 percent. Always. Europe’s range is a bit wider, but not much.

If I took 200 years of unemployment rates and graphed them, and asked you to find where the assembly line took over manufacturing, or where steam power rapidly replaced animal power, or the lightning-fast adoption of electricity by industry, you wouldn’t be able to find those spots. They aren’t even blips in the unemployment record.

You don’t even have to look back as far as the assembly line to see this happening. It has happened non-stop for 200 years. Every fifty years, we lose about half of all jobs, and this has been pretty steady since 1800.

How is it that for 200 years we have lost half of all jobs every half century, but never has this process caused unemployment? Not only has it not caused unemployment, but during that time, we have had full employment against the backdrop of rising wages.

How can wages rise while half of all jobs are constantly being destroyed? Simple. Because new technology always increases worker productivity. It creates new jobs, like web designer and programmer, while destroying low-wage backbreaking work. When this happens, everyone along the way gets a better job.

Our current situation isn’t any different than the past. The nature of technology has always been to create high-skilled jobs and increase worker productivity. This is good news for everyone.

People often ask me what their children should study to make sure they have a job in the future. I usually say it doesn’t really matter. If I knew everything I know now and went back to the mid 1980s, what could I have taken in high school to make me better prepared for today? There is only one class, and it wasn’t computer science. It was typing. Who would have guessed?

The great skill is to be able to learn new things, and luckily, we all have that. In fact, that is our singular ability as a species. What I do in my day-to-day job consists largely of skills I have learned as the years have passed. In my experience, if you ask people at all job levels,“Would you like a little more challenging job to make a little more money?” almost everyone says yes.

That’s all it has taken for us to collectively get here today, and that’s all we need going forward.

0 comments:

Post a Comment