And the reasons have as much to do with psychology as they do with finance, operations, experience or subject matter expertise. JL

Joe Wiggins reports in Behavioral Investment:

For many decisions there are only a handful of information points that are relevant, distinct, and materially impact the probability of a positive outcome. (But) noise can be mistaken for relevant information, we feel more confident in a decision if it is ‘supported’ by more evidence and information that was once relevant ceases to be so because of some ‘regime shift.’ It is difficult not to focus more on the accumulation of information rather than seek to identify the information that matters (all while) more information can lead to us becoming more overconfident and poorly calibrated in our judgements.

It is without question that investors now have easy access to more information than ever to guide decision making; optically, this surfeit of data appears to be a positive – who doesn’t want more ‘evidence’ to inform their judgements? Yet there are a number of potential drawbacks, most notably the challenge of disentangling signals from a blizzard of noise in order to make consistent decisions. For this post, I want to specifically address the potential consequences of information growth and its impact on our precision and confidence levels. Whilst we often believe that more information can improve our accuracy (the number of correct decisions we make), in certain situations all it may be doing is increasing our (unfounded) confidence.

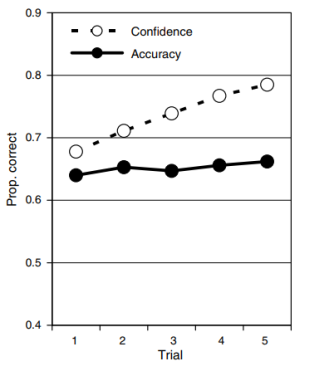

There have been a number of studies in this area, the majority of which reach similar conclusions. Tsai, Klayman and Hastie (2008)[i], tested the impact of additional information on an individual’s ability to predict the results of college football games and their confidence in doing so correctly. Participants in the study had to forecast a winner for a number of games based on anonymised statistical information. The information came in blocks of 6 (so for the first round of predictions the participant had 6 pieces of data) and after each round of predictions they were given another block of information, up to 5 blocks (or 30 data points), and had to update their views. Participants were asked to predict both the winner and their confidence in their judgement between 50% and 100%. The aim of the experiment was to understand how increased information impacted both accuracy and confidence. Here are the results (taken directly from the study):

The contrasting impact of the additional information is stark – the accuracy of decision making is flat, decisions were little better with 30 statistics than just 6, however, participant confidence that they could select the winner increased materially and consistently. When we come into possession of more, seemingly relevant, information our belief that we are making the right decision can be emboldened even if there is no justification for this shift in confidence levels.

For this research, the blocks of information were provided at random and the participants were amateurs – would the same relationship hold for professionals who were able to select the information they believed to be most pertinent? An unpublished 1973 study by Paul Slovic (cited by the CIA[ii]), takes a similar approach but in this case with experienced horse race handicappers. Unlike in the college football study, the handicappers were allowed to rank the available information by perceived importance (from a list of 88 variables) and then had to predict the winner of an anonymised race when in possession of 5 pieces of information, then 10, 20 and 40 (by order of their specified preference / validity). The results obtained were consistent with the aforementioned football study – accuracy was consistent despite more information becoming available, but confidence increased as the number of available statistics rose.

There are two important issues for investors to consider when looking at this type of outcome: i) There are probably less relevant pieces of information than we think, ii) There are a number of negatives around the accumulation of too much information – one of which is overconfidence.

More information does not necessarily lead to better decisions: In the investment industry it can often feel as if it is the amount of information or evidence that matters, rather than its validity. Provided a research report is long enough, the conclusion must be sound. I would contend, however, that for many investment decisions there are only a handful of information points that are relevant, distinct, and materially impact the probability of a positive outcome. If this is the case, why is there such a desire for more and more information?

– We don’t know what that relevant information is, therefore we include everything we can find.

– We struggle to realise that many pieces of information are telling us the same thing.

– In random markets, noise can be mistaken for relevant information.

– If a decision goes wrong, we at least want to show that we did a lot of research to support it.

– It is difficult to sell our investment wares if we simplify our decision making to a select few variables.

– It we make simple decisions based on a narrow range of information we can look lazy, inept and unsophisticated.

– We feel more comfortable / confident in a decision if it is ‘supported’ by more evidence.

– It is possible that information that was once relevant ceases to be so because of some ‘regime shift’.

This combination of factors (and others I have failed to mention) means that it is incredibly difficult not to focus more on the accumulation of information rather than seek to identify the information that matters.

More information can lead to overconfidence: It is not simply the case that more information might not result in greater decision making accuracy, but that it can lead to us becoming more overconfident and poorly calibrated in our judgements. Whilst we often believe that ‘new’ information bolsters the case supporting our choices, on many occasions this additional evidence may simply be a repetition of prior information (merely in a different guise) or be erroneous with no predictive power (a major problem in an environment marked by uncertainty and randomness where things that look like they matter, actually do not). As we receive more information, therefore, we are prone to believe that we are more accurate in our decisions, when there is often no justification for this. This can create an anomalous situation where behaviour consistent with being diligent and thorough, actually results in worse investment decisions being made.

Judging the balance between carrying out sufficient research and becoming overly confident by collecting reams of superfluous data is fraught with difficultly, however, all investors should think more about what is the most relevant information, rather than concentrate simply on the accumulation of more. For professional investors, a simple idea is to decide which pieces of information they would use if there was a restriction (of say only 5 or 10 items) and then monitor the outcomes of decisions made utilising only these select variables. Such an approach forces us to think about what evidence really matters to us, whether it is effective and what value we might add over and above such a basic method.

0 comments:

Post a Comment