Microsoft, which once had such an advantage, but has lost it and now has to pay up to compete, creating a strategic disadvantage. JL

Ben Thompson reports in Stratechery:

The iPhone and iPad inspired demand in their own right. Apple had the users that developers needed to make money. For Windows, developers were cheap. That is no longer the case: This is the context for the acquisition of GitHub: lacking a platform with sufficient users to attract developers, Microsoft has to “acquire” developers through GitHub, a superior cloud with network effects. The problem is that acquiring developers in this way, without the leverage of users, it is hard to imagine GitHub generating revenue that justifies this purchase price.

Three developer-related announcements, two from Apple, and one from Microsoft. The former came as part of Apple’s annual Worldwide Developers Conference keynote:

Microsoft, meanwhile, for the second time in three years, outshone Apple’s keynote with a massive acquisition. From the company’s press release:

- The iOS App Store, which turns 10 next month, serves 500 million weekly visitors, and as of later this week will have earned developers over $100 billion.

- Sometime next year developers will be able to write apps for the Mac using iOS user interface frameworks (known as UIKit).

Microsoft Corp. announced it has reached an agreement to acquire GitHub, the world’s leading software development platform where more than 28 million developers learn, share and collaborate to create the future. Together, the two companies will empower developers to achieve more at every stage of the development lifecycle, accelerate enterprise use of GitHub, and bring Microsoft’s developer tools and services to new audiences.Developers can be quite expensive indeed!

“Microsoft is a developer-first company, and by joining forces with GitHub we strengthen our commitment to developer freedom, openness and innovation,” said Satya Nadella, CEO, Microsoft. “We recognize the community responsibility we take on with this agreement and will do our best work to empower every developer to build, innovate and solve the world’s most pressing challenges.”

Under the terms of the agreement, Microsoft will acquire GitHub for $7.5 billion in Microsoft stock.

Platform-Developer Symbiosis

Over the last few weeks, particularly in The Bill Gates Line, I have been exploring the differences between aggregators and platforms; while aggregators generally harvest already produced content or goods, developers leverage the platform to create something entirely new.

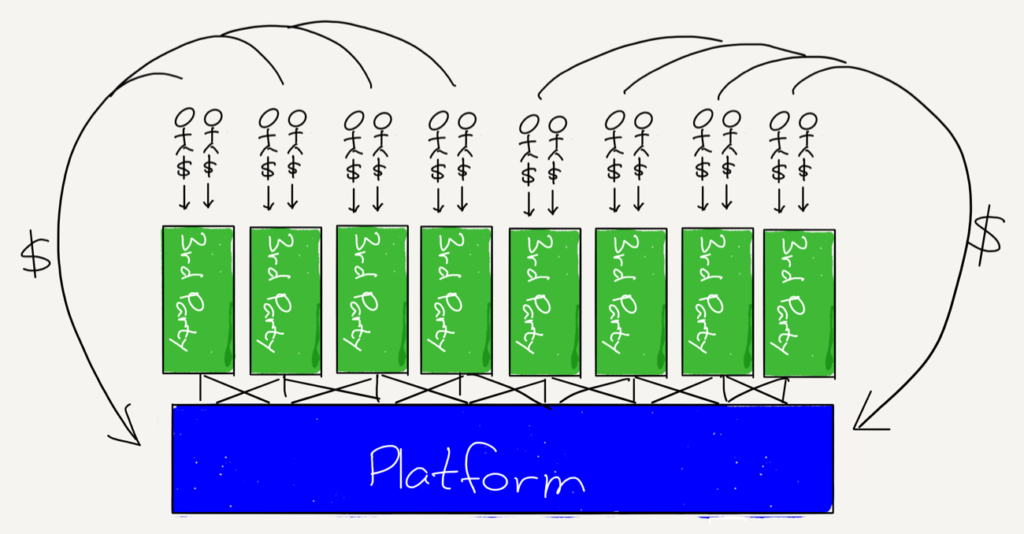

This results in a symbiosis between developers and platforms: from a technical perspective, platforms provide the fundamental building blocks (i.e. application program interfaces, or APIs) necessary for developers to build new experiences, and from a marketing perspective, those new experiences give customers a reason to buy the platform in the first place, or to upgrade.

The degree to which applications drive adoption of the underlying platform can, of course, vary; unsurprisingly the monetization potential of the platform relative to developers varies in a correlated way. Traditional Windows, for example, provided very little end user functionality; what made it so valuable were all of the applications built on top of its open platform.

Here “open” means two things: first, the Windows API was available to anyone to build on, and two, developers built relationships directly with end users, including payment. This led to many huge software companies and, in 2003, to the creation of a platform on top of Windows: Valve’s Steam.

What Valve realized is that playing a game is only one part of the overall customer experience; the experience of discovering and buying the game matters as well, as does the installation and upgrade process. Moreover, these customer pain points were developer pain points as well; the original impetus to develop Steam, for example, was the difficulty in getting players to upgrade en masse, something that was essential for games in which players competed online. And, while Valve is a private company and has never announced Steam’s revenue numbers, reports suggest the platform generates billions of dollars a year.

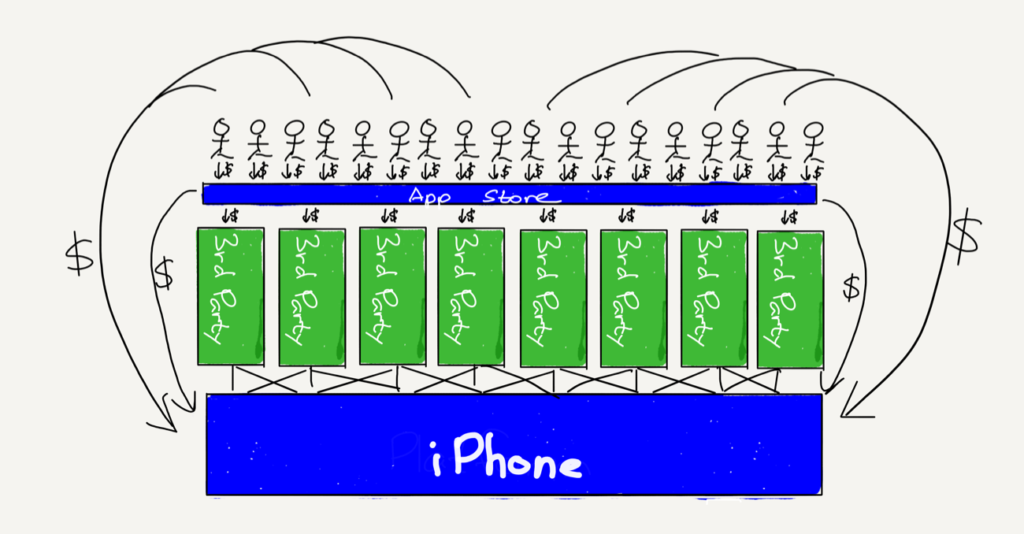

Even that, though, pales in comparison to the iOS App Store: Apple took Steam’s app store idea and integrated it with the platform, such that iOS users and developers had no choice but to use Apple’s owned-and-operated distribution channel, with all of the various limitations and costs — 30%, to be precise — that that entailed.

Apple was able to accomplish this first and foremost because the underlying products — the iPhone and iPad — inspired demand in their own right, independent of applications. Apple had the users that developers needed to make money.

Second, the App Store, like Steam before it, really was a better experience that drove more downloads and purchases by end users. This meant that developing for iOS wasn’t simply attractive because of the number of users, but also because those users were willing to buy more than they would have on another platform.

Third — and this applies to Steam as well — the App Store dramatically lowered the barriers to entry for developers; this led to more apps, which attracted more users, which led to more apps, both locking in apps as a competitive advantage and also ensuring that no one app had outsized power (leaving Apple free to restrict Steam-like competitors by fiat).

Apple’s Platform Announcements

This frames the two Apple announcements I noted above. Start with the news of $100 billion for iOS developers: that means that Apple has collected around $40 billion, and at a very high margin to boot.

Moreover, the vast majority of Apple’s announcements were, if anything, about competing with those developers: the first new app announced, Measure, should immediately wipe out the only obviously useful Augmented Reality apps in the store. Apple also announced a new Podcasts app for Watch, update News, Stocks, and Voice Memo apps, and the only third party demos were about how one of the largest software companies there is — Adobe — would be supporting Apple’s preferred 3D-image format. And why not! The implication of owning all of those high-value users is that, on iOS anyways, developers are cheap.

The Mac, though, is a different story: the platform is far smaller than the iPhone; that there remain a number of high quality independent software vendors supporting the Mac is a testament to how valuable it is for developers to be able to build direct relationships with customers that can span years and multiple transactions. Still, there seems little question that the number of Mac apps is, if not trending in the wrong direction, certainly not growing in any meaningful way; there simply aren’t enough users to entice developers.

That means Apple’s approach has to be very different from iOS: instead of dictating terms to developers, Apple announced that it is in the middle of a multi-year project to make it easier to port iOS apps to the Mac. This is, in a fashion, Apple paying for Mac apps; no, the money isn’t going to developers, but Apple is voluntarily taking on a much greater portion of the porting workload. Developers are much more expensive when you don’t have nearly as many users.

The Cost of GitHub

Still, whatever it is costing Apple to build this porting framework, it surely is a lot less than $7.5 billion, the price Microsoft is paying for GitHub. Then again, at first glance, it may not be clear what the point of comparison is.

Go back to Windows: Microsoft had to do very little to convince developers to build on the platform. Indeed, even at the height of Microsoft’s antitrust troubles, developers continued to favor the platform by an overwhelming margin, for an obvious reason: that was where all the users were. In other words, for Windows, developers were cheap.

That is no longer the case today: Windows remains an important platform in the enterprise and for gaming (although Steam, much to Microsoft’s chagrin, takes a good amount of the platform profit there), but the company has no platform presence in mobile, and is in second place in the cloud. Moreover, that second place is largely predicated on shepherding existing corporate customers to cloud computing; it is not clear why any new company — or developer — would choose Microsoft.

This is the context for thinking about the acquisition of GitHub: lacking a platform with sufficient users to attract developers, Microsoft has to “acquire” developers directly through superior tooling and now, with GitHub, a superior cloud offering with a meaningful amount of network effects. The problem is that acquiring developers in this way, without the leverage of users, is extraordinarily expensive; it is very hard to imagine GitHub ever generating the sort of revenue that justifies this purchase price.

Again, though, GitHub revenue is not the point; Microsoft has plenty of revenue. What it also has is a potentially fatal weakness: no platform with user-based leverage. Instead Microsoft is betting that a future of open-source, cloud-based applications that exist independent of platforms will be a large-and-increasing share of the future, and that there is room in that future for a company to win by offering a superior user experience for developers directly, not simply exerting leverage on them.

This, by the way, is precisely why Microsoft is the best possible acquirer for GitHub, a company that, having raised $350 million in venture capital, was possibly not going to make it as an independent entity. Any company with a platform with a meaningful amount of users would find it very hard to resist the temptation to use GitHub as leverage; on the other side of the spectrum, purely enterprise-focused companies like IBM or Oracle would be tempted to wring every possible bit of profit out of the company.

What Microsoft wants is much fuzzier: it wants to be developers’ friend, in large part because it has no other option. In the long run, particularly as Windows continues to fade, the company will be ever more invested in a world with no gatekeepers, where developer tools and clouds win by being better on the merits, not by being able to leverage users.

That, though, is exactly why Microsoft had to pay so much: buying in directly is a whole lot more expensive than using leverage, which can produce equivalent — or better! — returns for much less investment.

0 comments:

Post a Comment