It seemed obvious to Apple, but consumers may take some convincing. JL

John Paczkowski reports in BuzzFeed:

Apple is arguing that the future of audio is wireless, that the world’s current assumptions about mobile audio are not only antiquated, but worthy of immediate abandonment. “We’ve got this 50-year-old connector — just a hole filled with air — and it’s just sitting there taking up space, really valuable space”

Apple VP Greg Joswiak is grinning as he holds up what is easily the smallest iPhone adapter I have ever seen. iPod white and about the length of a matchstick, it’s designed to connect audio headphones with an industry standard 3.5-millimeter analog plug to the Lightning port on Apple’s newest iPhone, which no longer bears the industry standard jack they require to work.

“This time, we’re putting an adapter in every box,” Joswiak quips, a wry nod to the backlash evoked in 2012 the last time Apple killed a widely used iPhone port — a move that rendered thousands of peripherals designed to interact with it incompatible without a $29 adapter, and pissed off legions of people in the process.

Apple is no stranger to killing things people use all the time — and even love. But the headphone jack? It’s on a whole other level than disc drives or ports named after their number of pins. The headphone jack predates not only Apple, but computers themselves. And it is ubiquitous. So, when you’re killing a century-old standard around which the entire audio industry developed, it’s wise to take precautions.

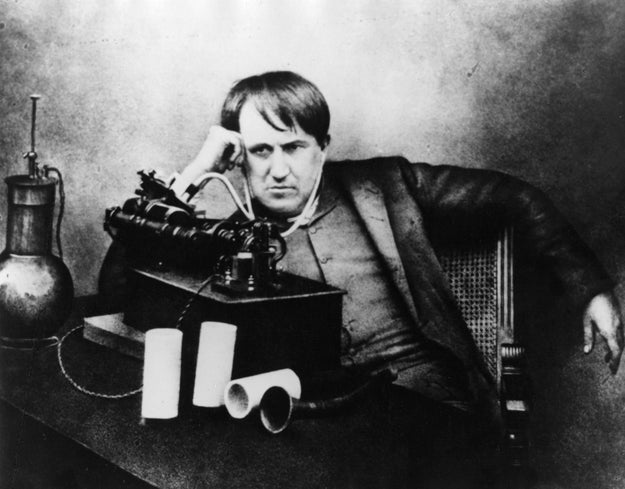

Invented for use with telephone switchboards in the late 1800s, the audio jack is among the oldest existing electrical standards. Originally 6.35-millimeter in width, it was reduced to 3.5-millimeter in the ’60s, a transformation that made it pervasive across most every piece of electronic audio equipment you can think of — home stereos, car stereos, camcorders, guitar amps, laptops, airplane entertainment systems, cochlear implants, smartphones, and — until today — the iPhone.Thomas Edison listening to a phonograph through primitive headphones. Getty Images

Apple is arguing that the future of audio is wireless, that the world’s current assumptions about mobile audio are not only antiquated, but worthy of immediate abandonment. In a world of Spotify and Sonos, it’s tough to disagree. But right now that future comes with a price: You’ve got to leave behind the perfectly good headphones you own and you’ve got to purchase the new wireless ones as an iPhone accessory. It’s up to Apple to make the case that this is a worthwhile exchange.

“The audio connector is more than 100 years old,” Joswiak says. “It had its last big innovation about 50 years ago. You know what that was? They made it smaller. It hasn’t been touched since then. It’s a dinosaur. It’s time to move on.”“It’s a dinosaur. It’s time to move on.”

Perhaps, but “if not now, when” is hardly a good argument when there are two pairs of reasonably high-end headphones in my desk that require that connector and every audio device I own has a 3.5-millimeter port. So does my car. And my laptop. The last plane I flew on. The alarm clock in my hotel. Microphones. Speakers. Baby monitors. Audio equipment and accessories purchased in every stage of my life. Everything. That little jack is in everything.

Historically, Apple has been pretty savvy about moving away from legacy standards and adopting new technology. Historically, this has been because whatever new tech Apple has adopted has delivered value orders of magnitude greater than whatever it replaced. Many have pointed to the floppy drive as a previous example of Apple’s willingness to kill off a widely used standard to make way for the future. But the thing is, when Apple scrapped the iMac’s floppy drive, the floppy disc was ferociously inadequate as a storage solution and in obvious need of replacement.

The 3.5-millimeter audio jack, however, is neither inadequate nor in obvious need of replacement. Sure, it is certainly dusty. But it is widely used and unencumbered by patents. You don’t have to pay anyone to use it. The signal it transmits doesn’t need to be decoded. And because it is an analog and not a digital standard, it cannot be locked down with digital rights management (DRM). Like the AC power socket adorning the walls of our homes, the headphone jack is a dumb interface. In Apple parlance, “it just works.” Buy a pair of headphones — from an audiophile store or an airport vending machine — and plug them into a headphone jack and you’ll likely hear whatever it is you were planning on listening to. So why send it off for a dirt nap?

For Dan Riccio, Apple’s senior vice president of hardware engineering, the iPhone’s 3.5-millimeter audio jack has felt something like the last months of an ill-fated if amicable relationship: familiar and comfortable, but ultimately an impediment to a better life ahead. “We’ve got this 50-year-old connector — just a hole filled with air — and it’s just sitting there taking up space, really valuable space,” he says.The iPhone’s 3.5-millimeter headphone jack. iFixit / Via ifixit.com

Riccio has been at Apple since 1998, and he has had a hand in most all of the company’s marquee hardware. He’s fully on board with the company’s wireless narrative, as well: “In a world of mobile and cellular connectivity, the one wired vestige out there is this cable hanging from people’s ears to their phones — why?” he asks. But he’s far more interested in the ripple effect of advancements the removal of the audio jack set off in the iPhone.

“It was holding us back from a number of things we wanted to put into the iPhone,” Riccio says. “It was fighting for space with camera technologies and processors and battery life. And frankly, when there’s a better, modern solution available, it’s crazy to keep it around.”

It’s hard to imagine Apple’s hardware design team hamstrung by a diminutive legacy port. But when you’re dealing with a computing device with extraordinarily tight dimensional tolerances, there are bound to be challenges. Riccio spends a good 15 minutes explaining them. I’ll try to do it in two.

A tentpole feature of the new iPhones are improved camera systems that are larger than the cameras in the devices that preceded them. The iPhone 7 now has the optical image stabilization feature previously reserved for its larger Plus siblings. And the iPhone 7 Plus has two complete camera systems side by side — one with a fixed wide-angle lens, the other with a 2x zoom telephoto lens. At the top of both devices is something called the “driver ledge” — a small printed circuit board that drives the iPhone’s display and its backlight. Historically, Apple placed it there to accommodate improvements in battery capacity, where it was out of the way. But according to Riccio, the driver ledge interfered with the iPhone 7 line’s new larger camera systems, so Apple moved the ledge lower in both devices. But there, it interfered with other components, particularly the audio jack.

So the company’s engineers tried removing the jack.

In doing so, they discovered a few things. First, it was easier to install the “Taptic Engine” that drives the iPhone 7’s new pressure-sensitive home button, which, like the trackpads on Apple’s latest MacBook, uses vibrating haptic sensations to simulate the feeling of a click — without actually clicking. (Did we mention that Apple killed the physical home button too?) Taptic Engine vibrations will also be used to deliver feeling specific notifications — hitting the end of a scrolled page, for example. And because Apple has given developers an API for it, an awful lot of other stuff as well — particularly in games.

“You can’t make it feel like there’s an earthquake happening, but the range of customization lets you do an awful lot,” Apple SVP Phil Schiller explains. “With every project there are things that surprise you with the meaning they take on as you start to use them. The Taptic Engine API is one of them. It turned into a much bigger thing than we ever thought it would be. It really does transform the experience for a lot of software. You’ll see.”

Second, there was an unforeseen opportunity to increase battery life. So the battery in the iPhone 7 is 14% bigger than the one in its predecessor, and in the iPhone 7 Plus, it’s 5% bigger. In terms of real-world performance gains, that’s about an additional two hours and one hour, respectively. Not bad.

Even better, removing the audio jack also eliminated a key point of ingress that Riccio says helped the new iPhone finally meet the IP67 water resistance spec Apple has been after for years (resistant when immersed under 1 meter of water for 30 minutes).

The 3.5-millimeter audio jack has been headed to its inevitable fate for some time now. If it wasn’t the iPhone 7, it might have been the iPhone 8 (or, for that matter, the iPhone 6). In the end, it was simple math that did the audio jack in, a cost-benefit analysis that sorely disfavored a single-purpose Very Old Port against a wireless audio future, some slick new cameras, and the kind of water resistance that anyone who has ever dropped an iPhone in the toilet has long wished for.

When you think about the iPhone, you probably think of it as a single gadget. So it’s helpful to step back and realize that it contains an array of formerly distinct devices sandwiched together. When Steve Jobs introduced the original iPhone in 2007, he said that it wasn’t one device, but three: “a widescreen iPod with touch controls, a revolutionary mobile phone, and a breakthrough internet communications device.”Apple

And as it turns out, among the features people most care about in a high-end smartphone — enough so that Apple is willing to spend millions of advertising dollars to remind you of its dominance, and upend a decades-old standard — is the camera.

“End-to-end these camera systems are a massive jump in capability over the ones in the 6s,” Schiller says when I observe that the iPhone 7 and 7 Plus have the same 12-megapixel cameras as their predecessors. He rattles off a list of camera geek specs to prove his point. They are faster, gather more light, have custom low-energy, high-performance chipsets and a bunch of near-future, gee-whiz stuff. Much of this is impenetrable: A slide in Apple’s Wednesday keynote presentation proudly touts a new image signal processor’s ability to calculate 100 billion operations in 25 milliseconds, for example. But it all comes together for me when I see a stunning un-retouched aerial shot of Coney Island that was, incredibly, shot on a phone.

“The new iPhones are crazy powerful,” says Neill Barham, founder and CEO of Filmic, a highly regarded mobile video app for iOS. He’s effusive in his praise, saying Apple’s new A10 chip has brought a “seismic” improvement in video processing to the iPhone. He jokes that Stanley Kubrick probably would have loved the 7 Plus, though he concedes he probably wouldn’t have shot Barry Lyndon with it.

“In layman’s terms, the prior 6S/+ is like a sprinter: it can do a lot of work in a short amount of time,” Barham offers. “The 7, on the other hand, is more like a marathon runner, or better yet, a triathlete that can perform multiple processor intensive loads all day long.”

At a small vineyard in the Santa Cruz Mountains far above Silicon Valley, a brief camera demo. Panoramas, portraits, Live Photos, close-ups, video of the vineyard dog that wanders into our group with a well-chewed tennis ball. To my nonprofessional photographer’s eye, everything looks really good. The images are sharp, vibrant. The new wide color capture support Apple has built into the iPhone makes the orange of a California poppy appear psychedelic. On the iPhone 7 Plus, switching between the two side-by-side cameras is pretty much seamless; the changes between the wide and tele lens occur so quickly and smoothly you don’t notice them. It feels like a single camera. With the zoom, I can just barely see pick-stitched lines of glue affixing a wine label to its bottle.Shot on iPhone 7 Plus at 2x optical zoom Courtesy of Apple.

A few months from now, Apple will roll out a software update that adds a new camera feature to the iPhone 7 Plus. It’s called “Portrait,” and it basically creates a bokeh effect — a sharply detailed subject in the foreground set against a soft, out-of-focus background. Because both cameras in the 7 Plus can be run simultaneously, it can capture nine layers of depth from foreground to background. And it can display them in real time. So when you’re in Portrait, you’ll be able to see that bokeh effect and, crucially, whether it’s worth using or not.

“Is it a better bokeh effect than the one you’d get with a Leica M and a 50-millimeter lens?” Schiller said earlier. “Of course not. But have you ever seen anything like it in a smartphone before?”

Nope.

But a “coming soon” camera advancement isn’t exactly the sort of tectonic smartphone innovation we’ve come to expect from Apple — though Apple CEO Tim Cook thinks the changes in this year’s iPhone are pretty big. When I ask him if — after a run of tectonic innovations like FaceTime, Siri, and Touch ID — we’ve reached the point where we’re starting to exhaust the innovation possible in the smartphone, he disagrees — diplomatically — with the premise of my question.

“Innovation is making things better,” Cook says. “If you step back and look at the things that are most important to iPhone users, it’s the photos they take and the other stuff they use to build the diaries of their lives. So the camera updates, the software optimization that we’ve done, the increases in battery life, and then all the features in iOS 10? These things collectively are a huge advance forward.”

Earlier this year, Apple’s rumored plan to remove the headphone jack from the next iPhone was met with predictable outrage and apology, delivered from equally predictable soapboxes. (Nevermind that two other smartphone manufacturers had already released phones without the port.)

The headphone jack is great for delivering audio, widely used, and unencumbered by patents and digital rights management, critics argued. Why remove it, leaving only an Apple-proprietary digital port that might in some dystopian future be locked down with the very DRM schemes that Steve Jobs bemoaned in his 2007 essay “Thoughts on Music”? Why provide a diminutive headphone jack adapter that will cost me $9 to replace when I inevitably lose it? Why allow even for the possibility of a scenario in which I cannot play a song that I own, whether it be because of copy protection lockdown or a “This accessory has not been certified by Apple” error? How does Apple respond to critics who’ve described removing the headphone jack from the iPhone as “user-hostile”?

Schiller thinks it’s a silly argument. “The idea that there’s some ulterior motive behind this move, or that it will usher in some new form of content management, it simply isn’t true,” he says. “We are removing the audio jack because we have developed a better way to deliver audio. It has nothing to do with content management or DRM — that’s pure, paranoid conspiracy theory.”“That’s pure, paranoid conspiracy theory.”

For what it’s worth, USB audio has allowed for copy protection since the mid-2000s, and according to Abdul Ismail, USB-IF CTO and principal engineer at Intel, the recording industry guys don’t really use it. “Audio content owners are a lot more comfortable with not requiring copy protection,” he says. “It has been almost a decade since iTunes started selling DRM-free music, and illegal file sharing hasn’t been rampant.”

Beyond that, Lightning is a good portable high-fidelity audio solution. It’s a powered connection, so it can support things like noise cancellation in headphones that typically require batteries, and because it’s digital, it can provide a lot of granular control over the frequency response and whatnot (Audeze makes a pair of Lightning headphones with a 10-band EQ of -10 to +10 decibels for each band).

But that’s not the argument Apple is making. Remember, the future of audio is wireless. And while the company might be giving every iPhone 7 owner a pair of Lightning EarPods (and an adapter!), what it really wants is for them to buy a pair of wireless AirPods.

“It’s unbelievable to me still how much stuff we were able to cram in there,” says John Ternus, vice president of Mac, iPad, ecosystem, and audio engineering at Apple. “We do a lot of products that are just packed with technology, but these are arguably the most densely packed products we’ve ever made. There is NO wasted space. NONE.”Apple’s new wireless AirPods Apple

Ternus is referring to Apple’s new wireless AirPod headphones, and, according to the X-ray slide I saw earlier in the day, he’s not exaggerating. Inside each AirPod, there is an Apple W1 wireless chip (the company’s first), two accelerometers, two optical sensors, two beam-forming microphones, an antenna, and an incredibly small battery that can power it for five hours (listening; talk time is two hours), plus another three hours with a short 15-minute boost from a diminutive Lightning-based charging case. (“We were really focused on power efficiency,” Ternus says. “Maniacally focused.”)

But so what? They sound great. And they should, because Apple wants you to pay $159 for them when they ship in late October.

They’ve got a thoughtful buttonless design that relies on double taps and Siri commands to skip songs or make phone calls. And the process through which you pair them to the iPhone is about as dead simple and intuitive as it gets. Once you’ve paired your AirPods with your iPhone, Apple uses your iCloud account to pair them with your other Apple devices. Untethered from one another by any cords, they are fully, independently wireless. And they’ll work with anything running iOS 10, Watch OS 3, or MacOS Sierra.

AirPods use Bluetooth for their connection. Bluetooth headphones have historically suffered from a conga line of connectivity problems: onerous pairing, dropped connections, crappy sound. Apple is confident it’s solved them all with that W1 chip. “As you can imagine, by developing our own Bluetooth chip and controlling both ends of the pairing process there’s a lot of magic we can do,” Ternus says. “We use a Bluetooth connection, but cover it in a lot of secret sauce.”

Just what’s in the secret sauce, Apple won’t say. But AirPods have been in development for a while. “These are as advanced a project as Apple Pencil,” Schiller told me. “We started this project when we started the Watch project. We knew we needed a great wireless solution for audio. We said, ‘What if you could design what the future of headphones should look like?’ That’s what we asked the team to do.”“These are as advanced a project as Apple Pencil”

The combined promise of sound quality, a steady Bluetooth connection, the battery life, the voice control, and ease of pairing across devices, all free of wires — if it all works, these things do seem to provide value an order of magnitude greater than even the priciest wired buds. But it’s also up to Apple to sell these things, to convince people that they want them. That’s harder, but not impossible. (Aside: Yes, AirPods will work with non-Apple devices — but you won’t get any of that secret sauce. And yes, Apple will sell you a single AirPod should you

lose one.)

Returning the AirPods to their dental floss dispenser–sized charging case, they slot into their cradles with a quiet, magnetized click. A tiny green light illuminates. Reflexively, the 12-year-old boy in me — the same one that still recalls a Micronaut action figure whose magnetized limbs made a similar noise — exclaims, “Badass.” Blurted out more or less involuntarily, it’s a tacit acknowledgment of that surprise-and-delight thing that Apple’s still pretty good at evoking, and a reasonably apt two-syllable summary of the tech I’ve just seen.

I know a longtime iPhone user who’s something of an audiophile. He’s spent a fair bit of money on high-end headphones over the years. The other day he told me that if the next iPhone doesn’t have a headphone jack and there’s a marquee Android phone available that does, he’ll switch. He doesn’t want Lightning headphones or wireless buds. And he doesn’t want to carry an adapter. He just wants to use the headphones he likes. And he doesn’t think he’s alone. What would Apple’s leadership say to someone like him?

“We do understand that this might be a difficult transition for some people who love their wired headphones,” says Schiller. “But the transition is inevitable. You’ve got to do it at some point. Sooner or later the headphone jack is going away. There are just too many reasons aligned against it sticking around any longer. There’s a little bit of pain in every transition, but we can’t let that stop us from making it. If we did, we’d never make any progress at all. The question we ask ourselves when making transitions like these is, have we done all the right things to mitigate it and to explain it and to make what’s on the other side so good that everyone is happy with the change? We think we’ve done that.”

And that’s hardly an unreasonable answer. Remember, the iPhone 7 will come with Lightning headphones and an adapter for people who don’t want to give up their existing headphones. Though their $159 price tag will elicit gas faces in some, Apple’s AirPods have a pretty compelling wireless audio story. And space freed up by the now abandoned audio jack enabled significant improvements in the iPhone’s cameras and batteries.

And while critics will inevitably argue that iPhone 7 breaks with Apple’s pattern of significant updates on even-numbered years, perhaps all the rejiggering of the device’s innards is setting the stage for something else. 2017 marks the 10th anniversary of the iPhone, and some Apple kremlinologists believe the company could have some bigger changes in the pipeline.

In the meantime, Apple just has to navigate this headphone port transition.

“Remember, we’ve been through this many times before,” says Schiller. “We got rid of parallel ports, the serial bus, floppy drives, physical keyboards on phones — do you miss the physical keyboards on your phone? … At some point — some point soon, I think — we’re all going to look back at the furor over the headphone jack and wonder what the big deal was.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment