Alex Mayyasi reports in Price Economics:

People aged 25 to 54 spent more time on their phones than teenagers. Adults’ relationship with connectivity and technology is not helped by the fact that an increasing share of workers need to use social media at work. Social networks start as a place for teens to goof off, but once they monetize and find business applications, the adults arrive

If you watch the news or read articles on the Internet from time to time, you’ve probably heard that teenagers and Millennials are digital natives who constantly use Snapchat and Instagram and apps that only people who can’t legally drink know about.

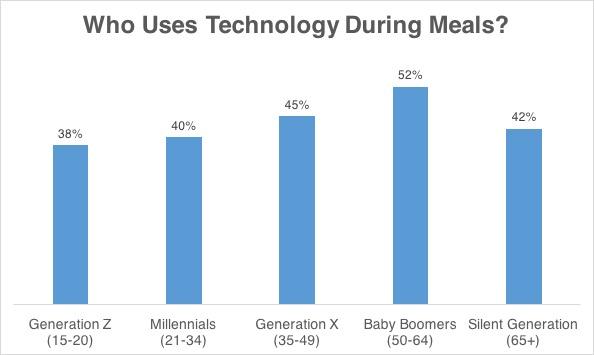

Teenagers check their phones 150 times per day, marketers tell us. They need instant gratification.They are "surfing paparazzi photos, logging onto Facebook... and uploading pictures of themselves while watching TV shows," says the author of a book called The Dumbest Generation.Young people “are interacting all day but almost entirely through a screen," adds a reporter at TIME Magazine.But if you want to characterize a large group of people, you want to have something to compare them to. And when you compare technology use among young people and middle-aged people, you discover something that, in hindsight, should seem pretty obvious—at least to always-connected working parents:Adults are as addicted—if not more addicted—to technology as teenagers.Here, for example, are the findings of a Nielsen survey about which age groups are most distracted by technology during mealtimes:Chart by Priceonomics; data via Nielsen Global SurveyThe above chart shows how many members of each demographic said that they use technology during meals. Contrary to their technology-obsessed image, teenagers led the way in terms of tech-free meals, followed by Millennials.Unfortunately Nielsen did not ask specifically about habitually pulling out smartphones during dinner. (This is why Baby Boomers rank so high: this data includes retired couples who watch Jeopardy during dinner.) But the survey results are a pretty remarkable repudiation of young people’s reputation as reliant on screens and technology.This really shouldn’t be surprising. After all, just imagine if teenagers wrote think pieces about how adults use technology.To say that American adults are always connected would be an understatement. One survey has found that over 50% of employees check their company email over the weekend and before or after work. Another found that 40% of employees think it’s fine to respond to important work emails during family dinners. Yet another revealed that most workers expect responses to emails within an hour if not in minutes.Whenever you read or hear something about teenagers’ obsession with Snapchat, remember to compare it to adults’ email addiction. Nearly 60% of adults check their work email while on vacation, and 6% have checked their email while a spouse is in labor. Another 6% have checked email at a funeral, and 10% at a child’s school event.Adults could defend themselves by pointing out that checking email is often a job responsibility, while teenagers sharing selfies on Snapchat are frittering away their time. There’s some truth to this, but there are plenty of possible retorts.For starters, there’s the fact that older adults set the policies that get everyone checking their work email constantly. They are the business owners and executives who expect instant responses.In addition, it’s an open question how often employees checking email really do so productively or out of necessity. In The Atlantic, Ian Bogost, a video game designer and researcher at the Georgia Institute of Technology, notes that people often turn to work email so they can feel productive:"Email pruning doesn’t enact work so much as it simulates work: It’s a ritual—like a secular, corporate rosary—which we perform in the hopes that it will somehow help us leave the domain of ineffectual work and re-enter the domain of gratifying productivity.”One could criticize young people’s micro-interactions on Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat as shallow connections that lack the depth of face-to-face conversations. But adults who check their email constantly may be searching for a similar illusion of productivity—a quick fix of feeling productive and important that pales in comparison to 90 minutes of focused work.There’s also the fact that American desk workers waste a substantial chunk of the workday using the Internet as the ultimate procrastination machine. According to Salary.com’s latest “Wasting Time at Work Survey,” 66% of workers report spending more than half an hour of each workday on social media. And remember, this is self-reported. If you were asked, do you think you’d underestimate how much time you spend on Facebook?Chart by Priceonomics; data from Salary.com's "Wasting Time at Work" 2014 SurveySalary.com’s respondents wasted the most time Googling, and over half of them said that they’d use their phones to wander the Internets if their bosses blocked procrastination sites.Plenty of parents and teachers have fretted about how kids can’t learn anything when they’re sneaking peeks at their phones during their class. But compared to the average desk worker who multitasks between work, Facebook, texting, and email, teenagers’ ability to take standardized tests and make it through a long period of chemistry is kind of impressive.*****Adults, of course, have written plenty of think pieces about their smartphone-addiction, and some particularly plugged-in workers have started attending “digital detoxes”—weekends without phones and computers.If you like to name your demons, psychologists Larissa Barber and Alecia Santuzzi have called the disease underlying adults’ smartphone addiction telepressure: “the combination of a strong urge to be responsive to people at work through message-based [information and communications technologies and] a preoccupation with quick response times.”Adults’ relationship with connectivity and technology is probably not helped by the fact that an increasing share of workers need to use social media at work—whether it’s marketers on Facebook, recruiters on LinkedIn, or all desk workers on Slack. Call it the ‘Slack Principle’: social networks start as a place for teens to goof off, but once they monetize and find business applications, the adults arrive. You start with teens on AOL instant messenger and end with consultants collaborating over Slack.This inclination to reach for our phones and fill empty moments with work emails is part of a world in which the average person spends—according to a report released last year by Informate, an intelligence firm that studies consumers’ mobile behavior—4.7 hours per day on his or her phone.Given that adults have to work, you might think that this average is high because of teenagers who live on their phones. But the opposite is true. Informate found that people aged 25 to 54 spent more time on their phones than teenagers.“While social networking may have started as a viral craze for U.S. teenagers,” the CEO of Informate has said. “It’s steadily matured into an everyday lifestyle for many adults around the world who are now eclipsing teens and young adults as most-frequent users.”This probably bears repeating: According to this report, at least, adults use their phones more than teens.The fact that adults can feel overwhelmed by being “always plugged in” is well documented. Articles, seminars, and speeches about our digital addiction and how to kick it are prevalent. It’s just that when people talk about adults’ smartphone fixation, they describe it as a problem that affects everyone. In contrast, discussion of how young people use technology often characterizes it as something particular to young people and linked to “kids these days” type criticisms.It’s worth considering: When we criticize teens who are glued to their screens, are we offering wise advice? Or are we projecting our own mixed feelings onto them?

0 comments:

Post a Comment