The Economist reports:

What has set apart Disney is its determination to put storytelling at the heart of its business, and its ability to get its hands on new characters capable of bringing fans back again and again. Disney is making a fortune and safeguarding its future by buying childhood, piece by piece

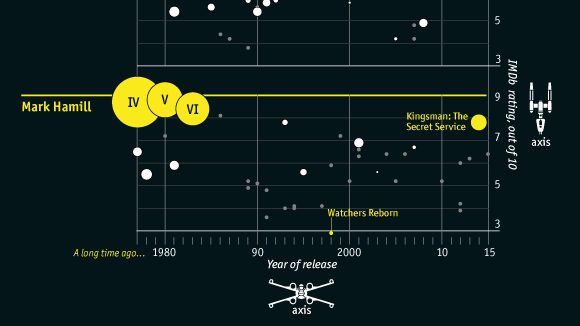

AS AUDIENCES left the premiere of the new Star Wars film, “The Force Awakens”, in Los Angeles on December 14th, its last image still alive in their imaginations, it became obvious that the hit of the year had arrived. Those at the screening saw plenty that is familiar from the original three episodes of the saga. Old characters from the 1980s Star Wars films are joined by a fresh generation of heroes to battle stormtroopers of a new evil galactic order. There is even a new hope of mysterious parentage on a desert planet, though now it is a woman, Rey, instead of Luke Skywalker. After three disappointing prequels the film is a return to form.

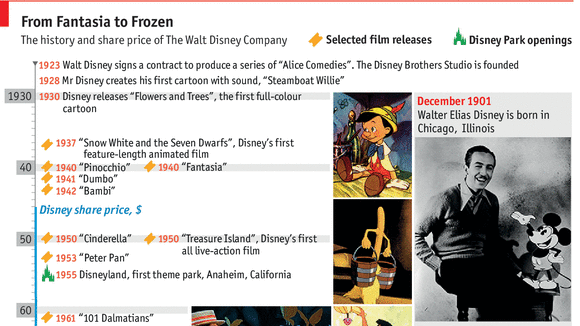

If “The Force Awakens” evokes the past, but on a grander canvas, Bob Iger, boss of the Walt Disney Company since 2005, has also set about remaking an original formula on a more ambitious scale. An intricate flow chart drawn in 1957 (pictured) elegantly lays out the company’s strategy, with films at the centre surrounded by theme parks, merchandise, music, publishing and television. Each piece of the business provides content and leads to sales for the others. Putting films back at the heart of the business is a reboot of the Disney family’s original scheme to dominate the entertainment industry by using content to appeal to a bigger, global audience. In remodelling itself to prize content over the means to distribute it, Disney has become the envy of the industry. Profits have more than doubled over the past five years, to $8.4 billion, and Disney’s share price has risen nearly fivefold in a little over a decade, easily beating its rivals. Comcast comes closest. Its share price has tripled in the same period; that of 21st Century Fox has doubled. Time Warner’s is up by only 20% and Viacom’s is lower. Disney is the most valuable of the lot, worth a star-studded $187 billion.

What has set apart Disney is its determination to put storytelling at the heart of its business, and its ability to get its hands on new characters capable of bringing fans back again and again. Disney’s purchase of Pixar Animation Studios and Marvel Entertainment brought Buzz Lightyear of “Toy Story” and Iron Man of “The Avengers” to a stable of mice and Muppets. Lucasfilm added Star Wars to the cast of characters that the firm has amassed since Mr Iger succeeded Michael Eisner as CEO.The way Walt wanted it

These new franchises have joined the world’s most formidable licensing and entertainment empire, one that encompasses toy shops, video games, theme parks, cruises, comics, music, television and feature films. Disney is commercialising childhood through lots of channels—and making the companies it bought, as well as itself, far more valuable in the process.

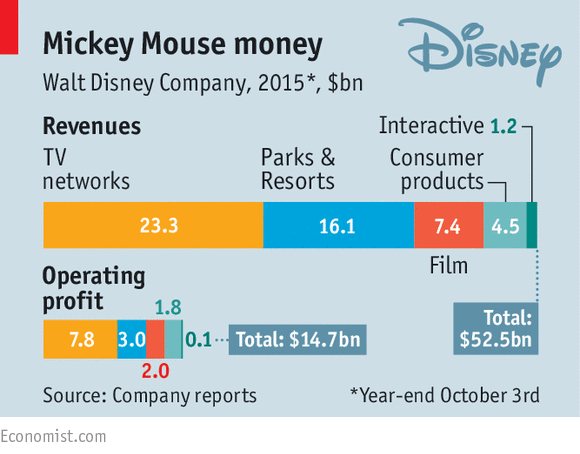

Stories should offer Disney protection against the currents sweeping across the industry. The most valuable parts of the entertainment giants’ empires are still their cable-TV businesses in America. ESPN, a sports channel that Disney acquired in 1996, as part of the purchase of Capital Cities/ABC, is a money machine. Cable networks bring nearly half of Disney’s revenues and profits (see chart). Disney’s competitors have pumped ever more cash into cable over the past decade and profits have risen steadily as the firms have expanded around the world.

A new dawnViewers, however, are starting to switch off. In rich countries many are now “cutting the cord” in favour of content delivered on-demand over the internet. The number of American households with pay-TV is expected to drop by 5m between 2014 and 2019, to 96.4m, according to eMarketer, a research firm. Cable’s decline is a reminder that the way audiences get content may change. In contrast, customers’ demand for great entertainment, irrespective of how they choose to receive it, is enduring. The firms with the most popular stories and characters will have the most bargaining power over whichever distributor, from Comcast to Netflix, finds favour. A decade ago the profits from ESPN and ABC helped Mr Iger pay for Pixar. In time his accumulation of content may make it easier to sell a streaming service directly to consumers who abandon cable.

Even when the future of cable looked bright, the Disney script was in need of a rewrite. It may have been a profitable business but it was also one that produced mediocre entertainment, and it was run by a man with an ego cartoonishly outsized even by Hollywood’s standards. Mr Eisner had turned around Disney himself two decades before, in part by reviving animation but in larger measure by turning Disney into a home-entertainment company, expanding its offerings on videotape, DVDs and on a variety of cable channels. But his relationships in Hollywood were fraying.

A shareholder lawsuit over his costly firing of Michael Ovitz, a former super-agent, ended in a court case that in 2004 aired ignominious details of Disney’s inner workings. The company’s film business languished. Jeffrey Katzenberg, responsible for a run of successes, quit in 1994 after a rancorous feud with Mr Eisner, and helped form a rival, DreamWorks SKG. In 2004 Disney had to fight off a hostile takeover by Comcast. Meanwhile, Roy Disney, Walt’s nephew, led a shareholder campaign to force out Mr Eisner and “save Disney”. The company was, as Mr Iger recalls, at war with everyone and itself.

Mr Iger joined Disney in 1996 when it bought Capital Cities/ABC. When he replaced Mr Eisner in 2005, he set about making peace. On his second day as CEO, he told the board that he wanted to buy Pixar, a ground-breaking animated-picture company that had been making films for Disney to distribute since “Toy Story” in 1995.

The empire strikes backThe idea had come to him the previous month at the opening of Hong Kong Disneyland. Almost none of the characters on the floats in the parade was from Disney’s own recent films. The ones that captured children’s imaginations were from Pixar. Disney’s own animation studio had been a mess since Mr Katzenberg had left in 1994, the year “The Lion King” was released and earned nearly $1 billion at the box office worldwide. “As animation goes, so goes the company,” Mr Iger told the board.

The problem was that Pixar was owned by Steve Jobs, never the easiest man to deal with and one of the many people with whom Mr Eisner had been feuding. Mr Iger paid Mr Jobs careful and attentive suit. He tailored his arguments for the merger to Mr Jobs’s concerns, stressing, for example, that Pixar would have creative independence, and, because it would be more insulated from the expectations of investors inside Disney, more creative freedom in another way: not every film would have to be a blockbuster, making the company or perhaps breaking it.

It probably did not hurt that Disney also paid Mr Jobs a great deal of money. When the acquisition went through in 2006 Disney spent $7.4 billion on Pixar, an incredibly high price for a company that produced one film a year. Mr Iger was also willing to splash out when he set up his 2009 deal with Marvel; that cost $4 billion, even though the film rights to two of its most valuable properties, Spider-Man and X-Men, were tied up elsewhere. And when he bought Lucasfilm, for $4.1 billion in 2012, it had not produced a new title in years, and the three newer editions of Star Wars, though commercially successful, had been sufficiently unpopular with fans that the success of another sequence of films was by no means assured.

Money was not the only factor. All three companies were owned by controlling masterminds who needed to be kept happy, and could not be wooed by riches alone. Like Disney’s own founder and Mr Jobs, Ike Perlmutter of Marvel and George Lucas had their own visions for their companies and products. Mr Iger’s delicate approach helped. He felt Disney had lost its creative edge; it was failing to produce compelling characters that could keep a franchise running for years. There was no evidence it knew better than its partners what would work best, and so he was willing to be hands off when needed.

Marvel, the next item after Pixar on Mr Iger’s shopping list, was not easy to pry from the hands of its reclusive boss. Mr Perlmutter, an Israeli-American self-made billionaire, is less famous than Mr Jobs and Mr Lucas, but no less fiercely protective of his business interests and of his privacy (he reportedly donned a disguise for the premiere of “Iron Man” in 2008). It took Mr Iger six months just to wangle a meeting.

A telephone call from Mr Jobs helped things along; a deal was finalised at the end of 2009. By this stage Mr Jobs was Disney’s largest individual shareholder—a status he attained in the Pixar deal—so it was in his interest to help. But he and Mr Iger had also become close friends and allies. Mr Iger was one of a very few people Mr Jobs trusted with news that his cancer had returned, telling him just before the announcement of the Pixar deal (and giving him a last-minute out if he wanted).

Some analysts suggested at the time that Mr Iger had overpaid for Marvel, not least because he was getting what appeared to be a B-team of superheroes. But Mr Iger’s faith in Marvel’s creative team and vision paid off. Marvel turned the story of a second-tier character, Iron Man, into a blockbuster. This became the cornerstone of a franchise introducing a number of other heroes, including Captain America and Thor, which built up to an ensemble film, “The Avengers”, that earned $1.5 billion around the world in 2012.

An Avengers sequel this year did nearly as well. Two more are in development and a plan for related projects extends into the middle of the 2020s. The success of the Iron Man and Avengers films has helped Marvel develop more obscure stories from its catalogue. With Disney’s financial might as backup, Marvel can take risks on eccentric films like “Guardians of the Galaxy”, which features a wisecracking raccoon and an ambulatory tree.

Nothing exemplifies the success of Mr Iger’s strategy better, though, than the Star Wars franchise, for which Disney paid $4.1 billion in 2012. “The Force Awakens” carries more gravitational force than the twin suns of Tatooine. Up to $5 billion in Star Wars licensed products will be sold over the next year. The film itself could rake in as much as $2 billion in ticket sales.

Return of the JediThe franchise encapsulates Disney’s long-term thinking. There are another five Star Wars films to come by 2020—two sequels to “The Force Awakens” and three stand-alone stories. By that time vast new Star Wars attractions will have opened in the firm’s theme parks in California and Florida. (Meanwhile Lucasfilm’s other blockbuster franchise, the Indiana Jones films, has a fifth title in the works with Harrison Ford to return to his starring role.)

Again, the deal that made this possible owed something to Mr Jobs. He had bought Pixar from Mr Lucas in 1986 and the two men knew each other; Mr Jobs’s experience with Pixar made the deal look good to Mr Lucas. So did Lucasfilm’s happy experience working with Disney on Star Wars theme-park attractions. And so too did a chance piece of past conduct.

Mr Iger had demonstrated his sensitivity to Mr Lucas more than 20 years before when, as an executive at ABC, he approved a second series of Lucasfilm’s “Young Indiana Jones Chronicles” despite poor ratings in the first season. Mr Iger felt Mr Lucas had lived up to his commitments to make a high-quality show and deserved the opportunity. When he broached the idea of buying Lucasfilm in 2011, Mr Lucas told him he had not forgotten the kindness. Mr Lucas, the founder and sole owner, never considered selling to anyone else.

That does not mean things were destined to go smoothly. The new Star Wars trilogy does not reflect Mr Lucas’s creative vision. He has described the sale as like a “divorce”. Yet the opening credit of “The Force Awakens” shows Lucasfilm’s green logo alone, without any mention of Disney. Mr Iger is not one to let his ego get in the way of a business deal and understands what matters to fans.

Disney has tried hard to preserve what Mr Iger terms the “creative essence” of the firms it has acquired, moving slowly when cutting costs or making administrative changes. A similar approach can be seen in the company proper, where individual business units enjoy more autonomy than they did under Mr Eisner.

In the case of Pixar, the leaving-well-alone was negotiated, from keeping its name on films in most markets to maintaining “beer Fridays” once a month at the studio’s headquarters in California. This hands-off approach did not stop Disney learning from Pixar. It transplanted Pixar’s film-maker-driven culture into Disney’s own animation studio, including the “Pixar brain trust”, a peer-review system and its notorious attention to detail. For “Frozen” researchers spent weeks in Norway studying local music, clothing, furniture and folk art. In 2013, it became the highest-grossing animated film ever, making close to $1.3 billion worldwide.

Getting its hands on Pixar helped reinvigorate Disney’s animation. It also gave all the firm’s other businesses new material to work with. That made all the Pixar properties—like those of Marvel—worth much more than if they had remained independent. Hit films create demand for merchandising and attractions and other entertainment, the success of which in turn creates more demand for more films, including not just sequels but also spin-offs that expand the universe of franchises. The power of these synergies is on display again with “The Force Awakens”.

The biggest doubt is the durability of the model. It is not clear for how long such franchises can be stretched. And introducing new ones is a risk. “John Carter”, a film based on one of a series of novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs, flopped. Cinema-goers will also have far more choice as other firms try to establish or add to their franchises. Universal has Fast and the Furious and Jurassic Park. Warner Brothers plans three more Harry Potter spin-offs and more from Marvel’s rival, DC Entertainment, which includes Batman and Superman.

No competitor, however, rivals Disney’s scale. The only media rival that comes close to matching its breadth is Comcast, which acquired NBC Universal, including Universal Studios and its theme-park business, in 2011. And none is anywhere near Disney when it comes to selling spin-off products. It is the world’s number-one licenser of merchandise by far, with $45 billion in sales in 2014, more than seven times as much as its closest competitor in Hollywood, Warner Bros.

Disney helped develop products and markets which Lucasfilm on its own would have been too stretched to consider. With Walmart it has made a Star Wars advertisement that targets girls as well as boys. Disney has cannily made Rey, a female character, the protagonist in “The Force Awakens”. The Disney effect could boost merchandising sales in America alone by five times what Lucasfilm could have managed by itself, according to Paul Southern, a licensing boss at Lucasfilm.

Disney also has a well-developed global retail network, and has been promoting Star Wars at its theme parks in Paris, Tokyo and Hong Kong. In 2016 Disney is opening a new theme park in Shanghai, the first of what might eventually be two in mainland China.

Mr Iger is due to step down in 2018. Can he stuff more into the toy box before he goes? Mr Iger keeps a list of firms Disney might be interested in buying. They are all leading international brands that would fit with Disney well. The Lego Group, a privately held Danish firm, already does business with the company, licensing products (including Star Wars) and placing shops at Disney’s theme parks. It would make an obvious target for the firm that has already bought up so many other pieces of your childhood.

0 comments:

Post a Comment