Charles Arthur reports in The Overspill:

This is a structural reality of how mobile is now. Buying Android and make it freely available was a defensive move to stop Microsoft being the gatekeeper to the mobile web.But search wasn’t actually the gatekeeper to mobile; having a well-stocked app store is. That’s where the searching really happens. Now Google faces the second stage of the mobile web.

Amit Singhal in 2011 showing a comparison of search volumes from mobile and “early desktop years”. Photo by Niall Kennedy on Flickr.

Amit Singhal, Google’s head of search, let slip a couple of interesting statistics at the Re/Code conference – none more so than that more than half of all searches incoming to Google each month are from mobile. (That excludes tablets.)

This averages out to less than one search per smartphone per day. We’ll see why in a bit.

First let’s throw in some more publicly available numbers.

• more than 100bn searches made per month to Google (total of desktop/ tablet/ mobile).

• about 1.4bn monthly active Google Android devices. (Source: Sundar Pichai, Nexus launch.)

• about 1 billion monthly active Google Play users. (Source: Sundar Pichai, Nexus launch.)

• about 1.5bn PCs in use worldwide.

• about 400m iPhones in use worldwide. Probably about 100m of those are in China. (Analyst estimates.)

• about 100m other smartphones in use (70m Windows Phones, 30m BlackBerrys)

• the mobile search market only generates a third as much revenue as the desktop. (Source: Rob Leathern, via the IAB 2014 report.)

Singhal had already said in July that mobile was larger than desktop in 10 countries; now it’s for the whole world. Google’s numbers effectively exclude China, of course, since Google doesn’t have any presence there. (Android phones and iPhones both use Baidu, the local search engine, as the default there; Google is banned from the mainland, and though people can use it, they overwhelmingly don’t.)

So let’s put these numbers together.

• In all, there are 1400 Google Android + 400 iPhones – 100 iPhones inside China + 100 other = 1.8bn smartphones in use outside China.

• 50bn mobile searches per month = 50bn per 30-day period

Today’s not the day to search

Calculate! 50bn / (1.8bn * 30) = 0.925 mobile searches per day. (Even if you exclude the Windows Phones and BlackBerrys, you still get 0.98 mobile searches per day.)

That’s right – the average (“mean”) person does less than one Google search on mobile per day. The mode (most common number) will be below that too. Over a 30-day period, the mean number of mobile Google searches is 27.8.

For desktop+tablet search, you get roughly the same figure – assume 1.5bn PCs and 300m tablets. But not all of those devices are available to make searches: many PCs are sitting in corporate environments where they aren’t connected to the internet, or can’t be used to make Google searches: think of all the machines in call centres, or functioning to run shop tills, or in factories. They reduce the potential base that can be used to make queries, and so ramp up the real average of per-active-PC/tablet monthly queries.

On the basis that

• the world PC installed base is split roughly 60-40 between corporate and personal users, so 900m and 600m

• guessing that 50% of those corporate machines, ie 450m, can’t make Google searches

then the total number of PCs/tablets available to make Google queries is 600m personal PCs + 450m corporate PCs + 300m tablets, or 1,350m devices.

Do the maths on 50bn searches per 30-day month across 1,350m devices and you get 37 searches per month, or 1.23 searches per day on average. The mode (most common figure) is likely to be 1, but the median (point where you have half as many behind as in front) will be higher. Probably not much higher – this will be an asymmetric distribution, where most of the (in)action is on the low end, so it may look like a Poisson or Pareto function.

Desktop: steady as she goes

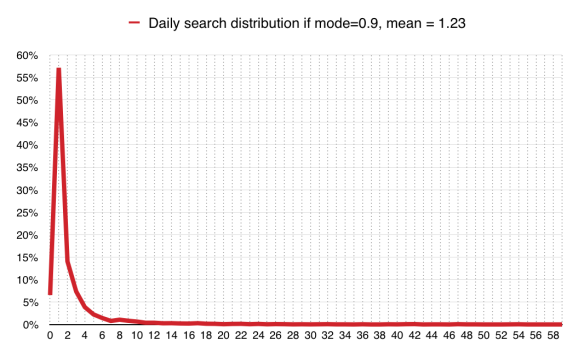

This is my rough model of how search distribution might look, generated by plugging figures we know into a Pareto generator and then doing a distribution function for N = integer number of searches per day.

Here’s how it looks for the desktop, using a mode (most common) of 0.9 searches per day and mean of 1.23:

What this is saying is that on any given day you get about 55% of people doing just one search, a bit less than 15% doing two searches, just under 5% doing four searches, and so on. Small proportions, but big absolute numbers. And who does what searches isn’t fixed; so someone who did zero searches yesterday might do 10 tomorrow. But equally, the 10-searcher yesterday does none or one or four today. And so on.

(It took some experimentation to get this shape; using a higher mode meant that the number doing zero searches was itself zero, which doesn’t make sense: there must be some people who by accident or design don’t ever hit Google during a day. Here, the proportion of users doing zero searches per day is 6.5%, which seems reasonable.)

Here’s how it breaks out when you look at cumulative percentages:

Note that lots of people don’t do many searches, but huge numbers of people do some searching. Further confirmation: the data release from AOL in 2006, which was just for desktop users, was “~20m records from ~650,000 users over three months” which translates to an average of 31 records per person over that 90-day period, or one-third of a query per day. AOL users in 2006 might not be directly comparable to Google users today, but it’s a useful check that the numbers here are probably broadly correct.

Incidentally, a lot of those present-day searches will be very low complexity. Watch people use a desktop. The most common Google query is “Facebook”. Probably the next most common? “Yahoo”, “Gmail” and “Hotmail”. People literally type those into the Google search box, or their browser search bar, to get to those sites. To a technical audience that’s stunning – why would someone do that? – but it’s observable behaviour. Remember the AOL data leak in 2006? Data there showed that some people used to just hit “Search” when the text box was empty which in turn meant that some advertisers got AdWords hits on the phrase “search terms” (which used to be the text in the box).

Mobile: all change

However on mobile, things are different. People do not, in general, type “Facebook” or “Gmail” into their mobile browser’s search bar. They go to the relevant app – Facebook or email. This behaviour is surely a big reason why mobile searches have been behind desktop for a long time, even though smartphones’ use has rocketed, and time spent on them is greater than for PCs, and they’ve been nudging a comparable installed base for some time.

Thus where someone using a desktop/laptop might fulfil their “average” one or two searches per day by typing “Facebook” when they open their browser, on mobile that doesn’t happen because it doesn’t need to happen; they just open the app.

For Google, that means it’s losing out, even though Google search is front and centre on every Android phone (as per Google’s instructions as part of its Mobile Application Device Agreement, MADA). People don’t, on average, search very much on mobile. The miracle of Google, in retrospect, is building a multi-billion dollar business by accreting millions of rare actions – people doing searches and then clicking on ads. Of course, Google has helped that latter activity by filling the top of its search results page with ads, and making them harder to distinguish from search results. But it’s still a hell of an achievement.

I tried modelling what search activity probably looks like on mobile: I used a mean = 0.925 (as per Singhal) and mode = 0.5. The mode must be below the mean because of the long tail of higher values; 0.5 is a guess, but moving it around doesn’t have a large effect. This gives a median of 0.94, close to the mean, which you’d also expect.

You can see that (if we allow these assumptions, which I think are reasonable – remember that they’re based on Google’s own data) then only 5% of users do more than seven searches per day on average. That’s very like the desktop scenario.

But here’s where things are suddenly very different from the desktop: although the proportion doing more than seven searches per day is about the same (5% or so), you have a far greater number who don’t ever get beyond zero.

Incidentally, this echoes Horace Dediu’s analysis from April 2014, when he noted how the internet population was growing rapidly, but Google’s revenues from non US/UK sources weren’t: US/UK users seemed to generate about $86/yr, while those outside that space generated only $12/yr. (This picture might be distorted by Google’s tax arrangements, of course.)

So there is the problem for Google: the PC base is static or even falling, while the number of people holding smartphones is growing. But the latter group tends not to use search, and so doesn’t see its most profitable ads. (There are in-app ads, but it’s never been very clear how much revenue they generate compared to other search ads. One suspects if they were very lucrative for Google it would be touting its “run rate” from them.)

Hence Google pushes people to use the mobile web more; and also, notably, to expand beyond simple search into services such as Google Now, Now On Tap, and pretty much anything. Seen through that lens, the reorganisation of Google into Alphabet makes sense: it’s seeking to get as many potentially moneymaking new ideas fired off as soon as possible, while search and search revenues are still growing, and before the growth of mobile really pulls the averages down. Dediu, in the link above, notes that 2016 will probably mark the point where internet population growth begins levelling off. And most of the new additions will be mobile-only.

You can see that effect most clearly in data from Google’s financials, where it discusses the number of paid clicks it gets, and the cost-per-click. It doesn’t take much effort to combine the two together to get the “total payments per click”.

What’s clear is that

(a) the number of paid clicks has zoomed up – increased nearly ninefold since the end of 2005 (where the graph starts)

(b) CPC is on a steady downward slope, despite Google’s best (and successful) efforts in mid-2011 to shore it up

(c) combining the two shows that revenue hasn’t increased nearly as fast as paid clicks. In other words, the new users and new platforms on which Google is available aren’t as valuable as the old ones.

In conclusion

So what do we conclude? Mobile search is a real problem for Google: people don’t do it nearly as much as you suspect it would like. But there’s no obvious way of changing that behaviour while users are so addicted to apps on their phones – and there’s no sign of that changing any time soon, no matter whether news organisations wish people would use mobile sites instead (clue: most people get their news via Facebook online).

This is a structural reality of how mobile is now. Buying Android and make it freely available was a defensive move to stop Microsoft being the gatekeeper to the mobile web (more in my book..).

But it turns out that search wasn’t actually the gatekeeper to mobile; having a well-stocked app store is. That’s where the searching really happens. Now Google faces the second stage of the mobile web. What will its answer be?

0 comments:

Post a Comment