MIT Technology Review reports:

If you live in a big city, you are more likely to catch flu but less likely to die of a heart attack or be diagnosed with diabetes, say public health scientists.

The science of allometry, the study of the relationship between body size and shape, is more than 100 years old. It dates to the late 19th century, when anatomists became fascinated by the link between the size and strength of appendages such as arms and legs in creatures of varying size.

In recent years, various researchers have begun to think of cities as “living” entities in which activity patterns change over regular 24-hour periods and which also vary dramatically depending on city size. That’s lead to a new science of city-related allometry—how various aspects of life vary with the size of the conurbation they take place in.

Today, we get a new insight into this emerging science thanks to the work of Luis Rocha at the University of Namur in Belgium and a couple of pals who have studied the way health varies with city size. These guys have made some surprising discoveries.

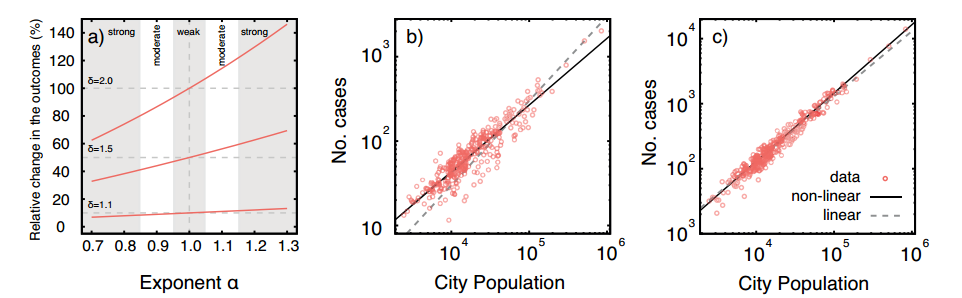

It’s easy to imagine that a city is simply the sum of its parts. But economists, sociologists, and city planners have long known that many aspects of city life do not scale linearly with the size of a city.

For example, the income and economic output of a city grow superlinearly—bigger cities have a greater output per capita than smaller ones. By contrast, the surface area of roads grows sublinearly with city size. And other factors grow linearly, such as the number of jobs, houses, and water consumption.

The reasons why aren’t always clear but a better understanding of this scaling is becoming increasingly important because of the general move of populations to cities. All over the world, cities are growing as the numbers of agricultural jobs fall and people go in search of fame and fortune in major conurbations.

An important factor in this is human health. So Rocha and co set out to investigate how health scales as cities get bigger—are people more or less likely to become ill, suffer accidents, increase their wellbeing and so on, as cities get bigger.

To find out, they gathered health related data about city dwellers in Brazil, Sweden, and the U.S. This data included rates of heart attacks, diabetes diagnoses, sexually transmitted diseases, suicides, car accidents, rapes, domestic violence, and so on.

The results are interesting. It turns out that the rate of infectious diseases, like chlamydia or meningitis, grows superlinearly with city size while the rate of heart attacks grows sublinearly. In other words, you’re more likely to catch flu in a bigger city but less likely to die of a heart attack.

The reasons for these differences aren’t hard to guess. People in bigger cities generally have contact with larger numbers of people and so are more likely to catch infectious diseases. Violent crime also grows superlinearly in big cities, possibly for the same reason: more contact with more people.

Big city dwellers are also less likely to commit suicide but why isn’t clear at all. One idea is that people in big cities benefit more from social networks and the support they provide.

At the same time, bigger cities also act like magnets for specialist hospitals and the professionals to staff them and this provides better treatment for heart attack victims. People also have better access to healthier food and tend to be more active which helps to explain the lower rates of diabetes although the sublinear relationship cold also be explained by better diagnosis in smaller cities.

And therein lies an important problem—how to interpret a relationship of this kind once it is found. Rocha and co are acutely aware of this problem: “The most important limitation of this methodology is that we are unable to make causal relations between population size and health outcomes,” they say.

The key point is that it is not straightforward to use the scaling of one quantity—city size, for example—to explain the scaling of another, such as mental well-being.

At least, not yet. And that’s why the science of metropolitan allometry is likely to become more interesting as bigger data sets become available and provide a new way to tease apart the extraordinary complexity of modern city living.

0 comments:

Post a Comment