How did we manage to get from dreck like 'The Real Housewives of New Jersey' to 'House of Cards' and 'Mad Men?'

After a century in which programming verified H.L. Mencken's assertion that 'no one ever lost money underestimating the intelligence of the American public,' from whence came this epidemic of good taste?

It will probably come as no surprise, as the following article explains, that this had little to do with taste and everything to do with the economics of bundled cable television contracts. In short, the big cable companies needed content, but none that would compete with the mainstream stuff it already had in abundance. What it needed were niche products that would generate just enough audience to pay the bills and keep the critics sullen but not mutinous.

So while we all look forward to the benefits of the unbundled future, it may well be that we owe our optimistic enthusiasm to the constraints of the old system. The king is dead, long live the king. JL

Derek Thompson reports in The Atlantic:

(Mad Men producer AMC) needed a niche hit—unique and craved by a large-enough, and enthusiastic-enough, audience that Comcast (and) Time Warner Cable would never dream of leaving the network off the bundle. Thus, the bizarre economics of cable became a signal to small networks on the verge of getting kicked off the money train: "Go for quality."

The Hollywood Reporter has a great behind-the-scenes history of Mad Men. There is some fun gossip: I didn't know, for example, that show-runner Matthew Weiner started working on the landmark drama while co-writing for Becker.

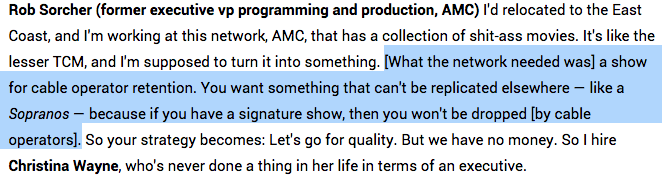

But the line that caught my eye was this elegant explanation for why you should thank your dreadfully unaffordable cable bill for the golden age of television.

"Cable operator retention"? What's Sorcher talking about?

AMC, like other cable networks, doesn't make most of its money from advertising. Instead, it makes most of its money from simply being on cable. The channel gets a few dimes from every household's monthly bill, whether or not they watch AMC. These dimes add up to several hundred million dollars a year in so-called "affiliate fees." Since only a tiny share of all cable households watch Mad Men, but all cable household pay for AMC, it's hardly an exaggeration to say that Mad Men only exists thanks to the millions of people who don't watch it.

But before it had Mad Men, AMC needed a very specific sort of hit to keep collecting these fees. It didn't need Two and a Half Men or NCIS. It didn't need a mainstream hit aimed squarely at the middlebrow. It just needed a niche hit—something unique and craved by a large-enough, and enthusiastic-enough, audience that Comcast, Time Warner Cable, and other operators would never dream of leaving the network off the bundle.

Thus, the bizarre economics of cable became a signal to small networks on the verge of getting kicked off the money train: "Go for quality."

Mad Men was, from the beginning, extraordinary—not merely beautiful entertainment, but also an abnormal television event; a shadowy, intimate drama with cinematic touches and methodical pacing. Compared with the most popular shows on TV, it hardly registers on the Nielsen radar. But as a media event, it has been a downright phenomenon. It has achieved exactly what Sorcher and AMC wanted. It was a cultural moment that not only helped AMC negotiate higher fees with cable providers but also made it a worthy destination for the show-runners behind slow-growing cult hits, like Breaking Bad, and mainstream behemoths, like The Walking Dead.

Today many people look forward to a TV future where consumers break away from the big bundle and buy our favorite shows or channels a la carte. It's easy to imagine how this scenario might be cheaper than paying for hundreds of channels you never watch. But as both Don Draper and the cable bundle's boom years come to an end together, let's pour one out for the profoundly unpopular business model made Mad Men possible in the first place.

0 comments:

Post a Comment