Fish stocks have dwindled as consumption has risen, driving purveyors to seek ever more obscure species to meet the ravenous demand.

And so it was that the Patagonian toothfish became the Chilean Sea Bass. Just as the slimehead became the Orange Roughy - or Norma Jean Mortenson became Marilyn Monroe (and Marion Morrison became John Wayne) or a remote frozen outpost was called Greenland to attract settlers, there is a long albeit not so noble tradition of assigning names to meet market expectations.

We are perfectly happy to let our imaginations drive our perceptions. That we are so easily led may even be a survival mechanism, encouraging us to try new things in the face of the innate human instinct for conservatism which could lead us to starve. We just have to hope that the rest of our senses continue to permit us to keep up with developments beyond our understanding.JL

Alex Mayyasi reports in PriceEconomics:

Until 1977, the name Chilean sea bass didn’t exist and few people ate the fish before the 1990s. Prior to that, scientists knew the fish by the less mouth-watering name of Patagonian or Antarctic toothfish.

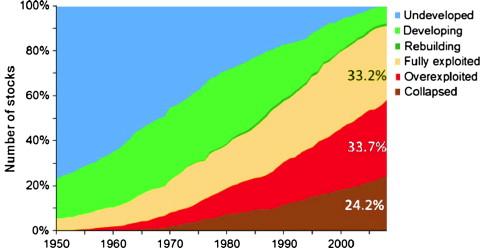

The Chilean sea bass is not the type of fish you find on the menu at Red Lobster or Long John Silver’s. Instead, you’re more likely to choose it out of a lineup that includes filet mignon and lobster risotto -- and to pay top dollar for its buttery, melt in your mouth flavor.Given its name, which conjures up exotic notions of South American fisherman carefully acquiring this prized fish off the coast of Chile, the price may seem appropriate. But only a minority of Chilean sea bass come from the coast of Chile. Many fish sold under the name hail from arctic regions. Moreover, the fish isn’t even a type of bass; it’s a cod. Until 1977, the name Chilean sea bass didn’t exist and few people ate the fish before the 1990s. Prior to that, scientists knew the fish by the less mouth-watering name of Patagonian or Antarctic toothfish.In short, the Chilean sea bass is a pure marketing invention -- and a wildly successful one. Far from unique, the story of the Chilean sea bass represents something of a formula in today’s climate of overfishing: choose a previously ignored fish, give it a more appealing name, and market it. With a little luck, a fish once tossed back as bycatch will become part of trendy $50 dinners.From Fish Sticks to the Four SeasonsDespite the oceans’ vast size, our appetite for their endowments appears even stronger.Collecting data on the state of fish populations is expensive and difficult enough to leave room for debate. That debate, however, is generally between doom and gloom like marine biologist Daniel Pauly’s assertion that we face the “end of fish” and other researchers’ cautious optimism about recovering stocks. Source: Froese and al. "What Catch Data can Tell Us About the Status of Global Fisheries" (2012) via The Washington PostThe above graph shows two researchers’ dire estimates of the state of fishing stocks, and it is the most popular fish that face the lowest supply. Pauly notes that over the past 50 years, cod, swordfish, and bluefin tuna populations have declined by some 90%.As populations of popular commercial fish dwindled, the seafood industry went further afield, although experts say operations now cover virtually every corner of the globe. Manufacturers turned to bycatch and ignored fish like the blue grenadier to make fish sticks and filet-o-fish sandwiches. Beyond fast food, sit-down restaurants, fish markets, and even sushi joints have taken to passing off ignoble fish as their more popular cousins. One study found 20% of fish in America to be mislabelled. The rate was 50% in California.The seafood industry also tapped new fish to offset the decline in major commercial offerings. The Washington Post writes, “As they went farther and deeper, fishermen have brought back fish that people didn't have recipes -- or even words -- for.” So, the fish received new, more refined names. In the seventies, seafood dealers renamed the slimehead, a fish named for its “distinctive mucus canals,” the “orange roughy.” Sales of the goosefish -- long thrown back by fishermen -- skyrocketed in the 1980s and 1990s once rechristened the monkfish. Rebranding sea urchins -- once known by Maine lobstermen as “whore’s eggs” -- under its Japanese name “uni” helped it catch on as a popular sushi ingredient now achieving popularity in other cuisine.An Exercise in BrandingSo how did the toothfish join the ranks of well-branded finds?As recounted in Hooked: A True Story of Pirates, Poaching and the Perfect Fish, in 1977 an American fish merchant named Lee Lantz was scouring fishing boats in a Chilean port. Lantz’s business was finding new types of fish to bring to market, and he became excited when he spotted a menacing looking, five-foot long toothfish that inspired him to ask, “That is one amazing-looking fish. What the hell is it?”The fishermen had not meant to catch the fish, which no one recognized. But as the use of deep-water longlines became more common, toothfish, which dwell in deep waters, started appearing in markets. Taking it for a type of bass, Lantz believed it would do well in America. But when he tried a bite of the toothfish, fried up in oil, it disappointed. It had almost no flavor. Nevertheless, as G. Bruce Knecht, author of Hooked, writes:[Lantz] still thought its attributes were a perfect match for the American market. It had a texture similar to Atlantic cod's, the richness of tuna, the innocuous mild flavor of a flounder, and its fat content made it feel almost buttery in the mouth. Mr. Lantz believed a white-fleshed fish that almost melted in your mouth -- and a fish that did not taste "fishy" -- could go a very long way with his customers at home.But if the strength of the toothfish (a name Lantz didn’t even know -- he learned that locals called it “cod of the deep”) was its ability to serve as a blank canvas for chefs, it needed a good name. Lantz stuck with calling it a bass, since that would be familiar to Americans. He rejected two of his early ideas for names, Pacific sea bass and South American sea bass, as too generic, according to Knecht. He decided on Chilean sea bass, the specificity of which seemed more exclusive.Despite its new, noble name, chefs in fancy Manhattan restaurants did not immediately serve a nicely broiled Chilean Sea Bass with Moroccan salsa over couscous. It took a few years for Lantz to land contracts for his new find. Initially, he made only a few small sales to wholesalers and other distributors despite offering samples far and wide. Finally, in 1980, a company struggling with the rising cost of halibut that the company used in its fish sticks bought Lantz’s entire stock, banking on people not tasting the difference between halibut and toothfish beneath the deep fry.From there, Chilean sea bass quickly worked its way up the food chain. Chinese restaurants purchased it as a cheap replacement for black cod (Chilean sea bass is, after all, a type of cod). Celebrity chefs embraced it, enjoying, as Knecht writes, it ability to “hold up to any method of cooking, accept any spice,” and never overcook. The Four Seasons first served it in 1990; it was Bon Appetit’s dish of the year in 2001.A Self-Fulfilling ProphecyAddressing new arrivals to Plymouth Plantation in 1622, Governor William Bradford apologized that all he “could presente their friends with was a lobster...without bread or anything else but a cupp of fair water."It may seem surprising that previously ignored fish like the toothfish and the slimehead (successfully rebranded as the orange roughy) could so quickly become the toast of the town. But with a long-term perspective, it becomes clear that the line between bycatch and fancy seafood is not a great wall defended by the impregnability of taste, but a porous border susceptible to the the effects of supply and demand, technology, and fickle trends. This is true of formerly low-class seafood like oysters and, most of all, the once humble lobster.In the early colonial days, lobster was a subsistence food. The biggest knock against lobster seems to be how plentiful it was. Food histories describe lobsters “washing ashore in two foot piles.” As wealth grew in colonial America, lobster remained a food primarily for prisoners, indentured servants, and the poor. Commercial markets were limited and a lobster bake would have had a status lower than a meal of fried chicken today.Lobster seems to have first found a mass market thanks to the advent of canning in the early to mid 1800s. Once canneries managed to convince skeptical Maine fishermen to become lobstermen, canned lobster could be found in inland stores, although still at one fifth the price of baked beans.But what made the lobster king were 19th century food tourists -- moneyed visitors to the New England coast from Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. These “rusticators” came looking for the “Yankee America of Myth,” so locals served them lobster for dinner on fine china with butter and herbs. Thanks to refrigeration, diners inland could pay top dollar for this new “luxury” of lobster.By then, lobster prices no longer reflected snob appeal. Between canning and the demand for lobster as a luxury purchase, lobstermen overfished. Whereas huge lobster were once laughably easy to pull up, finding one pound lobsters became the work of a professional. The exclusive image of the lobster became a self-fulfilling prophecy, reflecting its stocks in the real world.Each of the rebranded fish -- the slimehead turned orange roughy, the sea urchins turned uni, the toothfish turned Chilean sea bass -- experienced the same. After their successful branding helped make them part of high-brow cuisine, the stocks of each plummeted. Seafood Watch, a sustainable seafood advisory list, released guidelines on each as scientists worried about their possible extinction. In 2002, a mere 10 years after Chilean sea bass became popular, environmental groups teamed up with American chefs on a “Take a Pass on Chilean Sea Bass” campaign that encouraged chefs to take the fish of their menus.Before the campaign began, international agreements set quotas and other regulations on the capture and sale of toothfish, but advocates insisted the boycott was necessary given the prevalence of illegal poaching. In 2002, the Commerce Department estimated that ⅔ of Chilean sea bass sales were illegal. The incentives to ignore regulations were simply too high.This is well illustrated by the case of Antonio Garcia Perez, a Spanish fisherman with serious disregard for fishing regulations. Perez used longlines “that stretch over more than 15 miles and carry up to 15,000 baited hooks” to catch as many as 40 tons of Chilean sea bass in a day. As Knecht recounts in his book, Perez instigated “one of the longest pursuits in nautical history” in 2003 while fishing for toothfish around the Heard and McDonald Islands, two barren, volcanic islands located roughly equidistant between South Africa, Australia, and Antarctica. Spotted by Australian patrol boats, Perez ordered his ship to flee south toward Antarctica.Perez’s boat, the Viarsa, had 96 tons of Chilean sea bass on board worth $1 million. With an Australian ship giving chase, the Viarsa made directly for a storm of 75 mph winds. Knecht describes the ship ascending building-size waves that rocked the ship, bent the walls, and created “the impression that the hull was being pressed together like an accordion.” To protect a cache of a fish no one much cared about a decade earlier, the Viarsa raced 4,000 miles (more than the distance from California to New York) over 3 weeks until additional ships joined to trap it in the South Atlantic Ocean.Nature, NurturedIn the United States, the Food and Drug Administration oversees the labelling of seafood. But as The Washington Post reports, the agency generally doesn’t have a problem with people in the seafood industry marketing fish under new names, focusing instead on cases of fraud and mislabelling that leads to safety concerns. The FDA now recognizes Chilean sea bass as an accepted name along with Patagonian and Antarctic toothfish.It would be nice if market mechanisms kicked in to protect stocks of popular seafood. When lobster became popular and overfished, the difficulty of trapping them would increase the price, leading people to seek alternatives. Lobsters would have a respite until stocks increased and prices dropped, hopefully leading to a sustainable equilibrium over time.Unfortunately -- as shown by the story of Antonio Garcia Perez and the world’s fishing stocks -- nothing of the sort happens. People continue to pay for popular seafood, with high prices becoming a draw for fishermen rather than a deterrent for diners. The result is hard to enforce (and negotiate) regulations and a tragedy of the commons.The trajectory of the Chilean sea bass -- from almost unknown, to fish sticks, to a fine cuisine risking extinction in a mere 20 years -- shows just how much power seafood markets hold over the state of our oceans. That said, the effects of regulation and campaigns like “Take A Pass On Chilean Sea Bass” have had an effect. Seafood Watch notes the success in allowing some stocks to recover, and lists a number of responsible sources for acquiring toothfish.In the future, expect to see more examples like the toothfish turned Chilean sea bass. Partly due to chefs’ and foodies’ always looking for the hot new thing, but also because in the context of overfishing, we simply need new things to eat.

Source: Froese and al. "What Catch Data can Tell Us About the Status of Global Fisheries" (2012) via The Washington PostThe above graph shows two researchers’ dire estimates of the state of fishing stocks, and it is the most popular fish that face the lowest supply. Pauly notes that over the past 50 years, cod, swordfish, and bluefin tuna populations have declined by some 90%.As populations of popular commercial fish dwindled, the seafood industry went further afield, although experts say operations now cover virtually every corner of the globe. Manufacturers turned to bycatch and ignored fish like the blue grenadier to make fish sticks and filet-o-fish sandwiches. Beyond fast food, sit-down restaurants, fish markets, and even sushi joints have taken to passing off ignoble fish as their more popular cousins. One study found 20% of fish in America to be mislabelled. The rate was 50% in California.The seafood industry also tapped new fish to offset the decline in major commercial offerings. The Washington Post writes, “As they went farther and deeper, fishermen have brought back fish that people didn't have recipes -- or even words -- for.” So, the fish received new, more refined names. In the seventies, seafood dealers renamed the slimehead, a fish named for its “distinctive mucus canals,” the “orange roughy.” Sales of the goosefish -- long thrown back by fishermen -- skyrocketed in the 1980s and 1990s once rechristened the monkfish. Rebranding sea urchins -- once known by Maine lobstermen as “whore’s eggs” -- under its Japanese name “uni” helped it catch on as a popular sushi ingredient now achieving popularity in other cuisine.An Exercise in BrandingSo how did the toothfish join the ranks of well-branded finds?As recounted in Hooked: A True Story of Pirates, Poaching and the Perfect Fish, in 1977 an American fish merchant named Lee Lantz was scouring fishing boats in a Chilean port. Lantz’s business was finding new types of fish to bring to market, and he became excited when he spotted a menacing looking, five-foot long toothfish that inspired him to ask, “That is one amazing-looking fish. What the hell is it?”The fishermen had not meant to catch the fish, which no one recognized. But as the use of deep-water longlines became more common, toothfish, which dwell in deep waters, started appearing in markets. Taking it for a type of bass, Lantz believed it would do well in America. But when he tried a bite of the toothfish, fried up in oil, it disappointed. It had almost no flavor. Nevertheless, as G. Bruce Knecht, author of Hooked, writes:[Lantz] still thought its attributes were a perfect match for the American market. It had a texture similar to Atlantic cod's, the richness of tuna, the innocuous mild flavor of a flounder, and its fat content made it feel almost buttery in the mouth. Mr. Lantz believed a white-fleshed fish that almost melted in your mouth -- and a fish that did not taste "fishy" -- could go a very long way with his customers at home.But if the strength of the toothfish (a name Lantz didn’t even know -- he learned that locals called it “cod of the deep”) was its ability to serve as a blank canvas for chefs, it needed a good name. Lantz stuck with calling it a bass, since that would be familiar to Americans. He rejected two of his early ideas for names, Pacific sea bass and South American sea bass, as too generic, according to Knecht. He decided on Chilean sea bass, the specificity of which seemed more exclusive.Despite its new, noble name, chefs in fancy Manhattan restaurants did not immediately serve a nicely broiled Chilean Sea Bass with Moroccan salsa over couscous. It took a few years for Lantz to land contracts for his new find. Initially, he made only a few small sales to wholesalers and other distributors despite offering samples far and wide. Finally, in 1980, a company struggling with the rising cost of halibut that the company used in its fish sticks bought Lantz’s entire stock, banking on people not tasting the difference between halibut and toothfish beneath the deep fry.From there, Chilean sea bass quickly worked its way up the food chain. Chinese restaurants purchased it as a cheap replacement for black cod (Chilean sea bass is, after all, a type of cod). Celebrity chefs embraced it, enjoying, as Knecht writes, it ability to “hold up to any method of cooking, accept any spice,” and never overcook. The Four Seasons first served it in 1990; it was Bon Appetit’s dish of the year in 2001.A Self-Fulfilling ProphecyAddressing new arrivals to Plymouth Plantation in 1622, Governor William Bradford apologized that all he “could presente their friends with was a lobster...without bread or anything else but a cupp of fair water."It may seem surprising that previously ignored fish like the toothfish and the slimehead (successfully rebranded as the orange roughy) could so quickly become the toast of the town. But with a long-term perspective, it becomes clear that the line between bycatch and fancy seafood is not a great wall defended by the impregnability of taste, but a porous border susceptible to the the effects of supply and demand, technology, and fickle trends. This is true of formerly low-class seafood like oysters and, most of all, the once humble lobster.In the early colonial days, lobster was a subsistence food. The biggest knock against lobster seems to be how plentiful it was. Food histories describe lobsters “washing ashore in two foot piles.” As wealth grew in colonial America, lobster remained a food primarily for prisoners, indentured servants, and the poor. Commercial markets were limited and a lobster bake would have had a status lower than a meal of fried chicken today.Lobster seems to have first found a mass market thanks to the advent of canning in the early to mid 1800s. Once canneries managed to convince skeptical Maine fishermen to become lobstermen, canned lobster could be found in inland stores, although still at one fifth the price of baked beans.But what made the lobster king were 19th century food tourists -- moneyed visitors to the New England coast from Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. These “rusticators” came looking for the “Yankee America of Myth,” so locals served them lobster for dinner on fine china with butter and herbs. Thanks to refrigeration, diners inland could pay top dollar for this new “luxury” of lobster.By then, lobster prices no longer reflected snob appeal. Between canning and the demand for lobster as a luxury purchase, lobstermen overfished. Whereas huge lobster were once laughably easy to pull up, finding one pound lobsters became the work of a professional. The exclusive image of the lobster became a self-fulfilling prophecy, reflecting its stocks in the real world.Each of the rebranded fish -- the slimehead turned orange roughy, the sea urchins turned uni, the toothfish turned Chilean sea bass -- experienced the same. After their successful branding helped make them part of high-brow cuisine, the stocks of each plummeted. Seafood Watch, a sustainable seafood advisory list, released guidelines on each as scientists worried about their possible extinction. In 2002, a mere 10 years after Chilean sea bass became popular, environmental groups teamed up with American chefs on a “Take a Pass on Chilean Sea Bass” campaign that encouraged chefs to take the fish of their menus.Before the campaign began, international agreements set quotas and other regulations on the capture and sale of toothfish, but advocates insisted the boycott was necessary given the prevalence of illegal poaching. In 2002, the Commerce Department estimated that ⅔ of Chilean sea bass sales were illegal. The incentives to ignore regulations were simply too high.This is well illustrated by the case of Antonio Garcia Perez, a Spanish fisherman with serious disregard for fishing regulations. Perez used longlines “that stretch over more than 15 miles and carry up to 15,000 baited hooks” to catch as many as 40 tons of Chilean sea bass in a day. As Knecht recounts in his book, Perez instigated “one of the longest pursuits in nautical history” in 2003 while fishing for toothfish around the Heard and McDonald Islands, two barren, volcanic islands located roughly equidistant between South Africa, Australia, and Antarctica. Spotted by Australian patrol boats, Perez ordered his ship to flee south toward Antarctica.Perez’s boat, the Viarsa, had 96 tons of Chilean sea bass on board worth $1 million. With an Australian ship giving chase, the Viarsa made directly for a storm of 75 mph winds. Knecht describes the ship ascending building-size waves that rocked the ship, bent the walls, and created “the impression that the hull was being pressed together like an accordion.” To protect a cache of a fish no one much cared about a decade earlier, the Viarsa raced 4,000 miles (more than the distance from California to New York) over 3 weeks until additional ships joined to trap it in the South Atlantic Ocean.Nature, NurturedIn the United States, the Food and Drug Administration oversees the labelling of seafood. But as The Washington Post reports, the agency generally doesn’t have a problem with people in the seafood industry marketing fish under new names, focusing instead on cases of fraud and mislabelling that leads to safety concerns. The FDA now recognizes Chilean sea bass as an accepted name along with Patagonian and Antarctic toothfish.It would be nice if market mechanisms kicked in to protect stocks of popular seafood. When lobster became popular and overfished, the difficulty of trapping them would increase the price, leading people to seek alternatives. Lobsters would have a respite until stocks increased and prices dropped, hopefully leading to a sustainable equilibrium over time.Unfortunately -- as shown by the story of Antonio Garcia Perez and the world’s fishing stocks -- nothing of the sort happens. People continue to pay for popular seafood, with high prices becoming a draw for fishermen rather than a deterrent for diners. The result is hard to enforce (and negotiate) regulations and a tragedy of the commons.The trajectory of the Chilean sea bass -- from almost unknown, to fish sticks, to a fine cuisine risking extinction in a mere 20 years -- shows just how much power seafood markets hold over the state of our oceans. That said, the effects of regulation and campaigns like “Take A Pass On Chilean Sea Bass” have had an effect. Seafood Watch notes the success in allowing some stocks to recover, and lists a number of responsible sources for acquiring toothfish.In the future, expect to see more examples like the toothfish turned Chilean sea bass. Partly due to chefs’ and foodies’ always looking for the hot new thing, but also because in the context of overfishing, we simply need new things to eat.

0 comments:

Post a Comment