The earnings have often disappointed of late, but the company is still known as a place from which others can poach smart, well-trained managers - and as an enterprise that has shed any emotional attachment to any legacy line of products or services that no longer delivers.

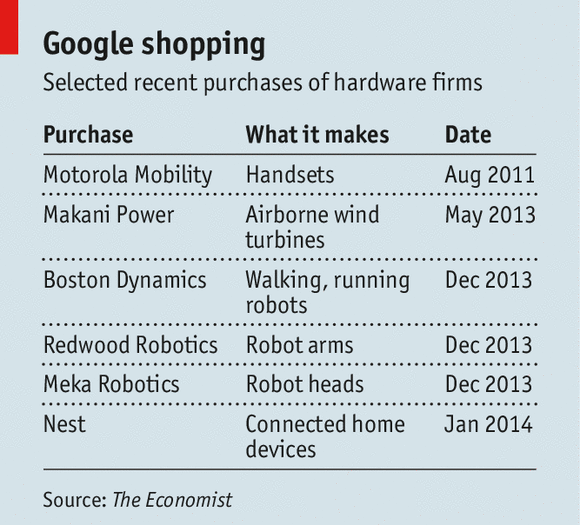

With the announcement that it is acquiring DeepMind, an London-based artificial intelligence firm it is buying for a reported $400 million, fresh on the heels of its $3.2 billion acquisition of Nest, Google appears to be signalling that it is putting its cash hoard to work, snapping up new opportunities in order to improve what it has - or lead it into new fields. This will both improve the delivery of services to which it is already committed (such as using DeepMind's AI capabilities to enhance search) and diversifying its profile in order to better manage risk while pursuing innovative sources of future growth (Nest).

The significant point is not whether either or both of these acquisitions will work out, but that Google recognizes the need to explore intelligent options in a variety of fields. Internet penetration will not deliver the kind of organic growth on which Google can simply allow itself to be carried. Facing similar strictures with electricity, GE has gone from being the vehicle Thomas Edison created to deliver his genius at the practical level of light bulbs, refrigerators and locomotives, to investing - for at least a time - in financial services, entertainment and environmental remediation. Some delivered extraordinary results but all were steps on a journey, not an end in themselves.

Google is indicating that it has embarked on a similar quest. JL

Ben Thompson comments in Strachery followed by comments from The Economist:

If you consider the three business models that are capable of being the foundation of multibillion-dollar businesses – consumer devices, ad-supported consumer services, and business software-as-a-service – Google just about maximized their potential in the ad-supported consumer services model.

Strachery:

Excepting the patent and panic-driven Motorola deal, prior to yesterday’s acquisition of Nest for $3.2 billion, the previous largest deal Google’s history was DoubleClick for $3.1 billion 2006. Beyond the similar dollar figures, it’s a deal worth considering for what it says about Google then and now.

With the acquisition of DoubleClick, Google solidified its hold on online advertising, putting the final touches on one of the most successful business models in tech history. As Horace Dediu has documented, the more people use the Internet, the more money Google makes, and that’s a pretty good wave to be riding. In the succeeding eight years, Google has certainly undertaken any number of initiatives, but the core business of the company hasn’t changed. Still, this has given Google a remarkable amount of freedom to pursue all kinds of businesses, from phone operating systems to residential fiber, with the understanding that as long as it increased Internet penetration, it was good for the bottom line.

Still though, there have been ever-so-perceptible cracks in the armor. Revenue and profit from Google’s own sites have dramatically outpaced revenue and profit from Google AdSense sites, after previously moving in lockstep. Revenue-per-click continues to drop, driving Google to not only try to increase the number of clicks, but also to ramp up their data and profile efforts, in an attempt to increase the value-per-click. Moreover, a surprisingly large amount of Google’s ad revenue is driven by just a few adwords.

Beyond, that, there are two other longer-range concerns with Google’s business model:

In short, if you consider the three business models that are capable of being the foundation of multibillion-dollar businesses – consumer devices, ad-supported consumer services, and business software-as-a-service – Google had just about maximized their potential in the ad-supported consumer services model.

- The growth rate in Internet penetration is set to peak in 2016. Were Google’s revenue and profit continues to track Internet penetration, then those metrics would peak as well

- A great number of Internet users today were not raised with computers; it’s fair to question how many of those clicking on Google ads falls in this group. As a new generation comes online, will ads continue to be effective at the scale Google needs them to be? I’m cautiously optimistic that advertising does not inevitably result in a terrible user experience, but there is certainly a point at which it does

Google’s New Business Model

Excepting the patent and panic-driven Motorola deal, prior to yesterday’s acquisition of Nest for $3.2 billion, the previous largest deal Google’s history was DoubleClick for $3.1 billion 2006. Beyond the similar dollar figures, it’s a deal worth considering for what it says about Google then and now.

With the acquisition of DoubleClick, Google solidified its hold on online advertising, putting the final touches on one of the most successful business models in tech history. As Horace Dediu has documented, the more people use the Internet, the more money Google makes, and that’s a pretty good wave to be riding. In the succeeding eight years, Google has certainly undertaken any number of initiatives, but the core business of the company hasn’t changed. Still, this has given Google a remarkable amount of freedom to pursue all kinds of businesses, from phone operating systems to residential fiber, with the understanding that as long as it increased Internet penetration, it was good for the bottom line.

Still though, there have been ever-so-perceptible cracks in the armor. Revenue and profit from Google’s own sites have dramatically outpaced revenue and profit from Google AdSense sites, after previously moving in lockstep. Revenue-per-click continues to drop, driving Google to not only try to increase the number of clicks, but also to ramp up their data and profile efforts, in an attempt to increase the value-per-click. Moreover, a surprisingly large amount of Google’s ad revenue is driven by just a few adwords.

Beyond, that, there are two other longer-range concerns with Google’s business model:

In short, if you consider the three business models that are capable of being the foundation of multibillion-dollar businesses – consumer devices, ad-supported consumer services, and business software-as-a-service – Google had just about maximized their potential in the ad-supported consumer services model.

- The growth rate in Internet penetration is set to peak in 2016. Were Google’s revenue and profit continues to track Internet penetration, then those metrics would peak as well

- A great number of Internet users today were not raised with computers; it’s fair to question how many of those clicking on Google ads falls in this group. As a new generation comes online, will ads continue to be effective at the scale Google needs them to be? I’m cautiously optimistic that advertising does not inevitably result in a terrible user experience, but there is certainly a point at which it does

Enter Nest.1

In my estimation, this deal is not about getting more data to support Google’s advertising model; rather, this is Google’s first true attempt to diversify its business, in this case into consumer devices.

Certainly Google has already done a lot of work in this area, from self-driving cars to Glass to any number of internal projects. But, especially in the consumer market, technology is not nearly enough. With Tony Fadell and his team, Google is getting some of the best product people on earth. Just as importantly – because product is not enough either – they are also getting an entire consumer operation, including customer support, channel expertise, retail partnerships, and all the other pieces that are critical to making a consumer device company successful.

That is why I fully believe Fadell and Google when they say Nest will remain its own operation, and am inclined to give them the benefit of the doubt with regards to Nest data. This deal is not about the old Google, but about what is next; it’s a second-leg for the Google stool, and it’s arriving just in time.

Some additional notes:

- Apple: Not unexpectedly, many commenters are painting this as a loss for Apple, but I don’t think that’s true at all. I give a lot of credence to this report in Recode that Apple was never interested. Apple has a very simple business: they make personal computers, and they make accessories for computers. Certainly said computers are becoming ever more personal, and the accessories ever more smart, but they have never and, for the foreseeable future, will never be a diversified company. How many times does Tim Cook need to tell us that Apple focuses on just a few products? It’s funny how no one listens.

- Microsoft: This transaction really has nothing to do with Microsoft, which I suppose is all that needs to be said, but it is interesting that this in fact makes Google a “Devices and Services” business. That, famously, is Microsoft’s new strategy, but, in classic Microsoft fashion, the devices they are focusing on are the ones that were groundbreaking half a decade ago, and their services even older.

- Facebook: This transaction has even less to do with Facebook than with Microsoft, except to note that Facebook is where Google was when they acquired DoubleClick. They are just now figuring out how to make money, and will spend the next several years consolidating and growing that business. That’s fine: it’s the natural progression of any company. Maybe in eight years they’ll be buying what’s next.

- Amazon: All of those devices need to be bought somewhere. Oh, and services need to be hosted.2 Jeff Bezos is a smart dude.The Economist: AT GOOGLE they call it the toothbrush test. Shortly after returning to being the firm’s chief executive in 2011, Larry Page said he wanted it to develop more services that everyone would use at least twice a day, like a toothbrush. Its search engine and its Android operating system for mobile devices pass that test. Now, with a string of recent acquisitions, Google seems to be planning to become as big in hardware as it is in software, developing “toothbrush” products in a variety of areas from robots to cars to domestic-heating controls.

Nest takes Google into the home-appliance business, which is how another, much older American conglomerate got started. General Electric (GE) produced its first electric fans in the 1890s and then went on to develop a full line of domestic heating and cooking devices in 1907, before expanding into the industrial and financial behemoth that is still going strong today.

The common factor shared by GE’s early products was electricity, something businesses were then just learning to exploit. With Google’s collection of hardware businesses, the common factor is data: gathering and crunching them, to make physical devices more intelligent.

Even so, the question is whether Google can knit the diverse businesses it is developing and acquiring into an even more profitable engineering colossus—or whether it is in danger of squandering billions. Concern that the firm could make overpriced acquisitions has grown along with the size of its cash pile, now around $57 billion. Eyebrows were raised this week when the price for Nest was revealed. Morgan Stanley, a bank, reckons it represents ten times Nest’s estimated annual revenue. (Google’s executive chairman, Eric Schmidt, is a non-executive director of The Economist Group.)

Why fork out so much for a startup that makes such banal things as thermostats? Paul Saffo of Discern Analytics, a research firm, argues that Google is already adept at profiting from the data people generate in the form of search queries, e-mails and other things they enter into computers. It has been sucking in data from smartphones and tablet computers thanks to the success of Android, and apps such as Google Maps. To keep growing, and thus to justify its shares’ lofty price-earnings ratio of 33, it must find ever more devices to feed its hunger for data.

Packed with sensors and software that can, say, detect that the house is empty and turn down the heating, Nest’s connected thermostats generate plenty of data, which the firm captures. Tony Fadell, Nest’s boss, has often talked about how Nest is well-positioned to profit from “the internet of things”—a world in which all kinds of devices use a combination of software, sensors and wireless connectivity to talk to their owners and one another.

Other big technology firms are also joining the battle to dominate the connected home. This month Samsung announced a new smart-home computing platform that will let people control washing machines, televisions and other devices it makes from a single app. Microsoft, Apple and Amazon were also tipped to take a lead there, but Google was until now seen as something of a laggard. “I don’t think Google realised how fast the internet of things would develop,” says Tim Bajarin of Creative Strategies, a consultancy.

Buying Nest will allow it to leapfrog much of the opposition. It also brings Google some stellar talent. Mr Fadell, who led the team that created the iPod while at Apple, has a knack for breathing new life into stale products. His skills and those of fellow Apple alumni at Nest could be helpful in other Google hardware businesses, such as Motorola Mobility.

Google has said little about its plans for its new robotics businesses. But it is likely to do what it did with driverless cars: take a technology financed by military contracts and adapt it for the consumer market. In future, personal Googlebots could buzz around the house, talking constantly to a Nest home-automation platform.

The challenge for Mr Page will be to ensure that these new businesses make the most of Google’s impressive infrastructure without being stifled by the bureaucracy of an organisation that now has 46,000 employees. Google has had to overcome sclerosis before. Soon after returning as boss, Mr Page axed various projects and streamlined the management.

Nest is being allowed to keep its separate identity and offices, with Mr Fadell reporting directly to Mr Page. Google has also protected its in-house hardware projects, such as Google Glass and self-driving cars, from succumbing to corporate inertia by nurturing them in its secretive Google X development lab. It has also given its most important projects high-profile bosses with the clout to champion them internally. The new head of Google’s robotics business is Andy Rubin, who led the successful development of Android.

Such tactics are good ways to avoid the pitfalls of conglomeration. But to ensure success, Google will need to avoid another misstep. Its chequered record on data-privacy issues means that Nest and other divisions will be subject to intense scrutiny by privacy activists and regulators. Provided it can retain the confidence of its users on this, Google should be able to find plenty of new opportunities in both software and hardware that pass the toothbrush test and keep a bright smile on its shareholders’ faces.

0 comments:

Post a Comment