In the new economy mass and scale, at least in terms of the size of the enterprise, were supposed to be less important and have less potential value than the impact that frequently intangible or relatively miniscule initiatives might have.

Well, yes, but. There's nothing like a billion dollar 'liquidity event' to realign one's vision with one's bank account. As the following article explains, there have been few so-called 'unicorns' those IPOs of such size that they are rarely sighted (a distant cousin to the equally rare 'Black Swan' of financial crisis legend).

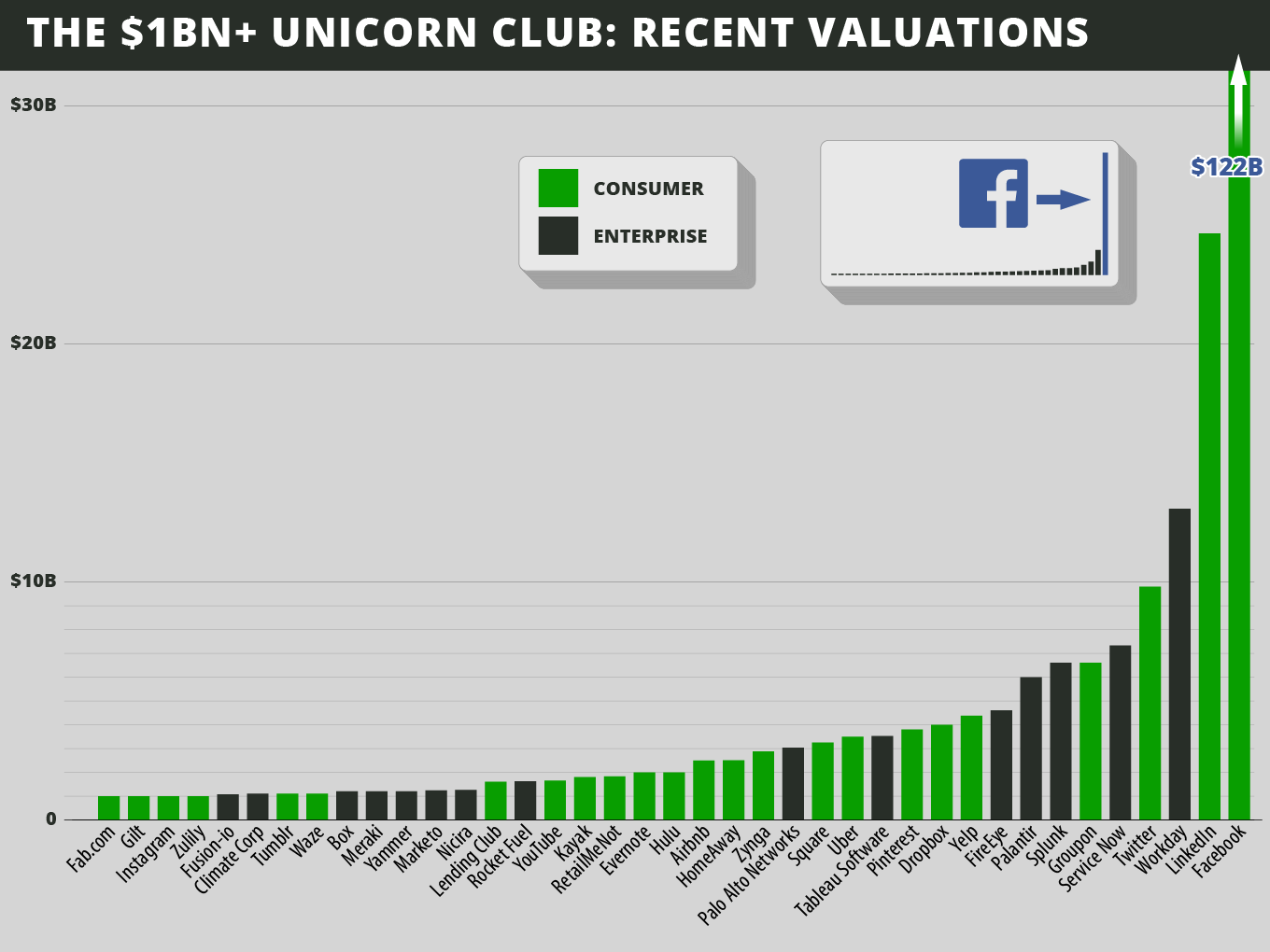

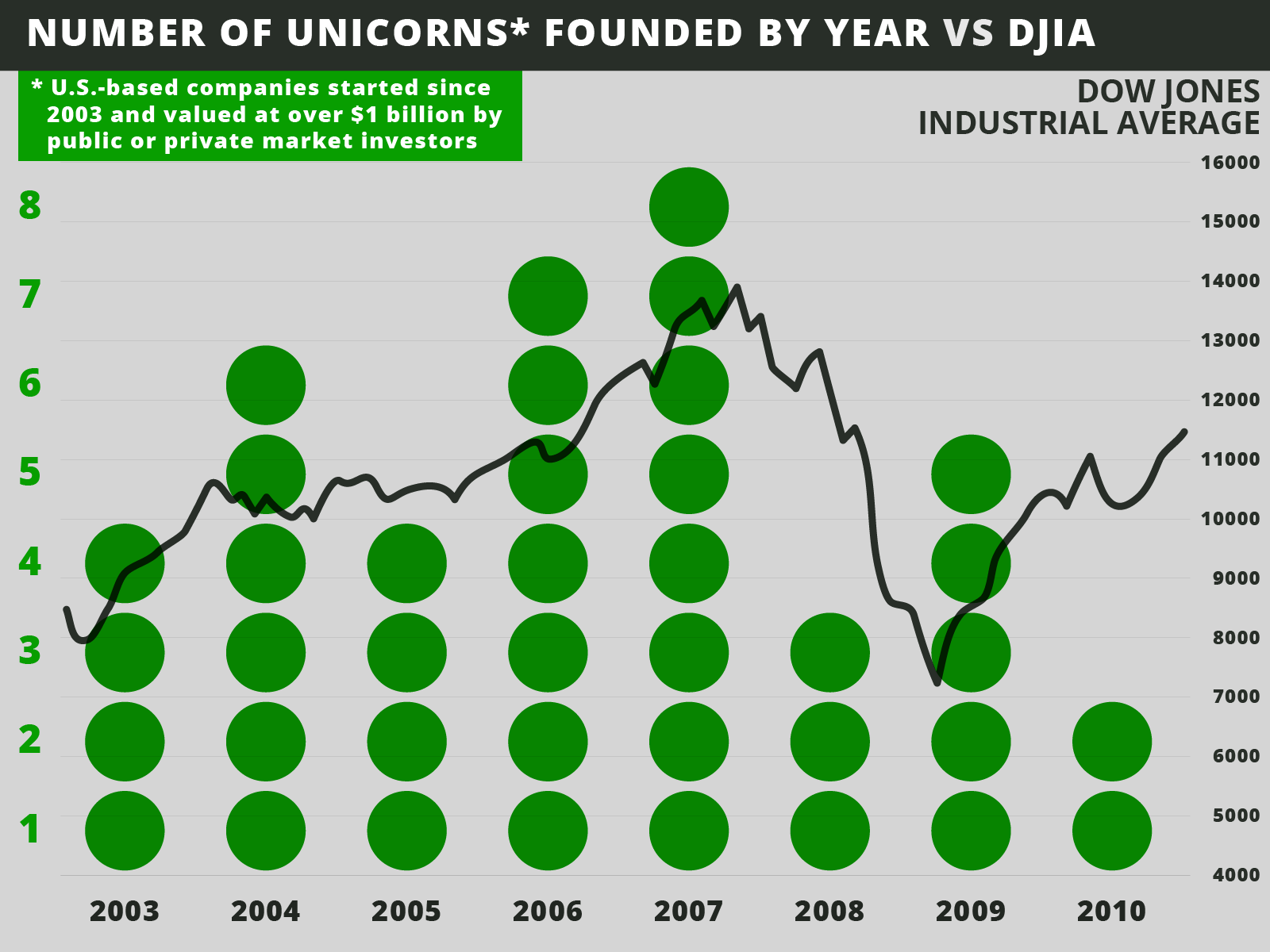

There have been 39 unicorns since 2003, to be precise, those IPOs that attained billion dollar size, or approximately .07 percent of the total that have gone public during that period. They share some common characteristics consistent with earlier research on success in the startup field: they tend to started by older, more experienced entrepreneurs, they are larger in terms of sales and number of employees as well as years in existence when ready to go public than common imagination might otherwise indicate and they tend to be consumer-focused, which makes sense given the consumer driven nature of most affluent economies.

They are as popular and highly sought after as they are rare because they draw attention to the entire field and draw in eager investors as well as consumers. In other words, size still matters, at least in certain aspects of human endeavor. JL

Aileen Lee comments in Tech Crunch:

Many entrepreneurs, and the venture investors who back them, seek to build billion-dollar companies.Why do investors seem to care about “billion dollar exits”?Historically, top venture funds have driven returns from their ownership in just a few companies in a given fund of many companies. Plus, traditional venture funds have grown in size, requiring larger “exits” to deliver acceptable returns. For example – to return just the initial capital of a $400 million venture fund, that might mean needing to own 20 percent of two different $1 billion companies, or 20 percent of a $2 billion company when the company is acquired or goes public.So, we wondered, as we’re a year into our new fund (which doesn’t need to back billion-dollar companies to succeed, but hey, we like to learn): how likely is it for a startup to achieve a billion-dollar valuation? Is there anything we can learn from the mega hits of the past decade, like Facebook, LinkedIn and Workday?To answer these questions, the Cowboy Ventures team built a dataset of U.S.-based tech companies started since January 2003 and most recently valued at $1 billion by private or public markets. We call it our “Learning Project,” and it’s ongoing.With big caveats that 1) our data is based on publicly available sources, such as CrunchBase, LinkedIn, and Wikipedia, and 2) it is based on a snapshot in time, which has definite limitations, here is a summary of what we’ve learned, with more explanation following this list*:Learnings to date about the “Unicorn Club”:

1) Welcome to the exclusive, 39-member Unicorn Club: the Top .07%

- That said, these 39 companies have shown it’s possible – and they do offer a lot that can be learned from.

2) Facebook is the super-unicorn of the decade (by our definition, worth >$100B). Every major technology wave has given birth to one or more super-unicorns

3) Consumer-oriented companies have created the majority of value in the past decade

Venture investing into early-stage consumer tech companies has cooled significantly in the past year. But it’s worth realizing that:

0 comments:

Post a Comment