Nepotism has been much in the news of late, what with JPMorgan and other western banks accused of hiring Chinese 'princelings,' the children of senior government leaders, so that their influence and 'golden Rolodexes' could be put to work for the advantage of the bank in question.

There have been other recent examples, as well, from Caroline Kennedy being named US Ambassador to Japan, to in-laws of the Spanish royal family being caught in spurious get-rich-quick scams that didnt work out so well.

It's not like the hiring of the offspring of the rich, famous and powerful in order to enhance the competitiveness of the enterprises who employ them is new. The Bible refers to this practice and even then it was probably old news.

The problem now - and the reason it is attracting more attention than it has in some time - is that stagnant economic prospects for the majority make the glaring abuse of privilege or access that much more difficult to bear. And it makes people that much less willing to tolerate it.

But the issue is not purely one of fairness. With resources scarce and returns uncertain, any practice that creates potential misallocations or inefficiencies further degrades the competitiveness and profitability of the institution doing so. This imposes additional disadvantages on the societies that tolerate it to the extent it becomes a dominant feature of the economy. Degrees from Ivy League schools in the US, England's Oxbridge, China's Tsinghua, France's grandes ecoles and other preferred educational eminences become self-reinforcing advantage mechanisms. So do jobs in finance or senior government agencies, the military etc.

The point is not that the practice be eliminated - it is too deeply ingrained in the human experience for that - but that its costs be properly assessed and explained. JL

Alex Mayyasi comments in the Priceconomics blog:

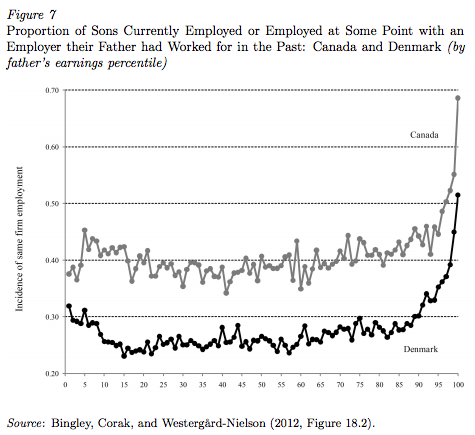

On an individual level, hiring well-connected scions of the Rockefellers of the day represents neither bribery nor scandal. But nationally, it’s a sociological fact with important consequences.

Isabel Dos Santos is one of 20 billionaires in Africa. She is the only African woman to grace Forbes’s billionaire list and Angola’s only billionaire.

Forbes added Dos Santos to the billionaire’s list this year at an estimated worth of $3 billion. Less than a year ago, however, she missed the cut with a net worth of $500 million that consisted primarily of stakes in two major Portuguese media companies.Dos Santos did not increase her wealth 6 times over in a year by selling a company she started or killing it on the stock market. Rather, Forbes discovered her undisclosed stakes in a variety of Angolan companies with the help of Angolan investigative journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais.The Angolan government cheered the announcement of Dos Santos’s billionaire status as a matter of national pride. But her success is a story of kleptocracy hidden under the respectable veneer of a business suit. Isabel Dos Santos is the oldest child of José Eduardo dos Santos, the strongman who has been Angola’s president since 1979, and her business career is one of taking rather than making.Forbes’ investigation into the source of Isabel Dos Santos’s wealth notes:Isabel Dos Santos’ formative business experience came at Miami Beach. Not the Florida city, but rather a rustic chic beachside bar and restaurant in Luanda that tries to emulate its namesake, down to the mediocre food and indifferent service. In 1997 the owner, Rui Barata, was having issues with health inspectors and taxmen. His solution: bringing in Isabel dos Santos, then 24, as his partner, with the idea, contemporaries say, that her name would keep pesky government regulators at bay. Her initial investment was negligible, according to a source with knowledge of the deal, and the restaurant thrived: Sixteen years later it’s still a weekend hot spot.The lesson–the equity stake available to those with a gilded name–couldn’t have been lost on Isabel dos Santos, who was entering adulthood at the exact same time Angola’s riches were being unlocked.Dos Santos grew up the daughter of a dictator. During a childhood that included “Christmas trees flown in from New York and $500,000 worth of bubbly imported from a Lisbon restaurateur,” Dos Santos garnered the nickname “the Princess.”But the gifts did not end with adulthood. Angola is a country whose government coffers swelled over the last decade as booms in commodity prices benefitted the resource rich country. Like any dictator, José Eduardo dos Santos faced the challenge of transferring those riches to himself in quasi-legal fashion and used state control over lucrative industries and public companies as the means to do so. In a number of deals he pushed and approved, he indirectly provided his daughter with stakes in the nation’s state run diamond company, Angola's first sanctioned private mobile phone company, a private bank that made lucrative loans to the state, and a state-owned oil company and major cement factory. Isabel dos Santos now uses the profits of her assets to make legitimate investments in Europe.Her story is hardly unique. Resource rich but rule of law poor countries throughout the world struggle with rulers who transfer public wealth to themselves, their family, and their supporters. In China, “princelings,” the sons and daughters of China’s senior leaders, have ridden on the coattails of their powerful fathers to prominent political or business positions. They benefit from privilege, nepotism, and outright corruption to easily amass wealth, all thanks to the gift of their name.Princelings are in the news this week because the Justice Department and Security Exchange Commission have begun investigating whether JPMorgan violated bribery laws by hiring the children of powerful Chinese regulators and state officials to win business for the firm. New York Times coverage provides one example:The bank hired the son of a former Chinese banking regulator who is now the chairman of the China Everbright Group, a state-controlled financial conglomerate, according to the document, which was reviewed by The New York Times, as well as public records. After the chairman’s son came on board, JPMorgan secured multiple coveted assignments from the Chinese conglomerate, including advising a subsidiary of the company on a stock offering, records show.The investigation is in initial stages and JPMorgan is cooperating. The biggest revelation so far is an internal spreadsheet in which JPMorgan explicitly linked their well-connected hires to specific deals. But as much as we enjoy a good banker bashing, JPMorgan may have done nothing illegal.This argument is made by Andrew Sorkin who notes that “hiring the well-connected isn’t always a scandal.” He acknowledges that if JPMorgan hired Chinese employees as “part of an expected quid pro quo” for business deals, especially if the hires did not do real work, then JPMorgan’s actions constitute bribery. But he also argues that hiring children of the wealthy and powerful for their “golden rolodexes” is standard procedure not just in China (where “virtually every [Wall Street] firm” has hired princelings), but here in the United States as well. Sorkin writes:By and large, financial firms in particular commonly hire people who have certain connections, whether through family or a business relationship. The thinking is that the new hire — and his or her last name — might “help open doors.” …Pick a big-name chief executive, and a quick LinkedIn search will often reveal a relative working for some other company that wants to do business with the parent’s company.Sorkin runs over examples of sons and daughters of powerful American executives and leaders hired by major firms. He notes that they are extremely qualified - often holding multiple Ivy League degrees with distinction and regarded as talented individuals. Given their qualifications, and the important role networks can play in business success, “It is a hard to fault a business for hiring someone who has better contacts than someone else.”But to us, this seems to represent a common problem of hiding behind meritocracy. It’s the same process of legitimation used by certain bankers who point to their degrees, intelligence, and long hours to disdain populist rhetoric and ignore any accusations that their lucrative business success comes thanks to government rents.Sorkin writes that it is common practice from Wall Street through blue chip businesses, government, lobbying, academia and media. He says “it is the way of the world.” But just how common is it, and how important are the results?Beside anecdotes and hand waving, the best data point of which we are aware is the following graph. It comes courtesy of economist Miles Corak in a paper (pdf) that exhaustively investigates America’s reduced socioeconomic mobility across generations with increased income inequality as its starting point.As the graph shows, sons often work at companies that once employed their father. But as you reach the upper income percentiles, the probability shoots up. You could say that as you approach the limit of the countries’ richest men, the probability that their son will work with one of their former or current employers heads toward 100%.We don’t have similar data for the United States, and the graph cannot prove messy questions of causality. But it strikingly visualizes a common sense notion - that the institutions capable of furnishing the largest incomes constitute a small world where the connections of growing up under the care of a politics or business magnate proves extremely valuable. Corak argues that this “intergenerational transmission of employers” is an important factor behind birth increasingly dictating economic outcomes.Businesses can’t be held responsible for rectifying inequality of opportunity. Hiring a bright, accomplished employee who also has a "golden rolodex" thanks to his or her last name makes sense.It may not be illegal or morally wrong. It may be understandable. But it’s a privilege and - even if not as clear cut as a dictator’s daughter nicknamed “princess” corruptly receiving a 25% stake in a state oil company - it’s a gift granted at birth and dishonest to pretend otherwise.

0 comments:

Post a Comment