At $99 or $199, this plastic model, dubbed 5C, is affordable in the middle class regions where the future growth is. It makes sense, but incites concern about debasing the brand. So, who's right, the elites or the populists?

First, forgive the irreverence of the accompanying illustration, but the annual release of new iPhones is as close to a religious experience as many people in this often secular world are likely to get. And if we're being honest, we think it's gotten so outta hand that there is a justifiable concern about worshiping false idols.

How the calculations led to the decision is an interesting journey inside the minds of one of the world's most iconic brands. Though written hours before the release, it reveals with remarkable insight the factors at play. No one is more conscious of the value of its brand than is Apple. But exclusivity can cut both ways. It can establish a reputation for quality and style that defies the ages. But it can also sap the vitality of a business starved for growth. In Apple's case, Android is dominating the global smartphone market. There comes a point where your reputation is secure, but your falling market share threatens your future prospects. That is where Apple found itself. The people who are going to buy this product want the brand. They will leave to those in certain neighborhoods of San Fran, London, Paris, Rio and NYC the pleasures of the 5C's upscale cousin, the 5S. Want the awesomest camera in the 'hood? You got it - just pay up. Just want to show your friends you bought an Apple? Well, now they got that covered, too.

This is about growth and stock prices and future innovations. Auto companies have been doing this for a century. And their experience shows it can work. The less expensive model is handsome and well made enough to be just fine for those who want it. And where are the ones who want something more luxurious going to go? Nokia? This is just the beginning of the middle innings of a very long game. JL

Ben Thompson comments in Stratechery:

Before the 5C was well-known, I argued that sticking with just one new iPhone model a year had a dangerous precedent: Ford, and the Model-T:

Still, the idea that Ford became overly focused on production as opposed to customer needs is a worrying one; if this fall brings nothing more than a 5S, with the same form factor as the 5, well, that will be great for production costs, but not so great for customers who prefer a larger phone, or a cheaper one (and remember, Cook is a production guy, not a product one).It was controversial to suggest Apple might add SKUs – heck, it’s still controversial today – even though the logic is inexorable.

A quick aside about pricing and segmentation

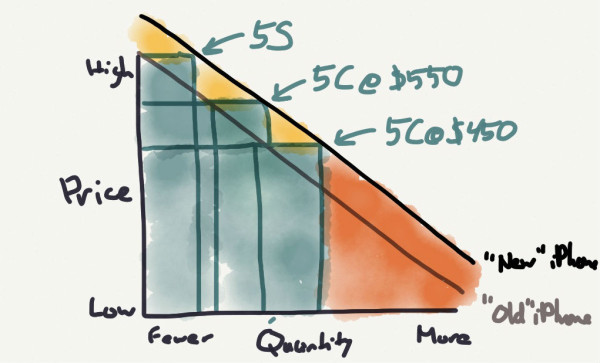

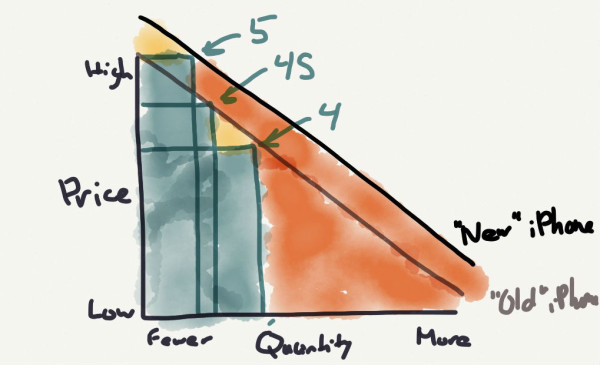

The most elementary thing to understand about pricing is the demand curve. In general, and as one might expect, the quantity sold has an inverse correlation to price.

The trouble with only selling one product is that you can only hit one spot on the demand curve; you don’t have a product for customers who fall lower on the demand curve (red in the illustration), and you are charging less than you could to those higher on the demand curve (yellow).

This is why companies typically sell multiple variations of a product; the idea is to also sell a higher-priced product that appeals to those willing to spend more, and a lower-priced product that attracts those lower down the demand curve. Ideally, the lower-priced product doesn’t cannibalize the higher-priced ones.

In this case, a company can capture much more of the value in the market.

Apple’s iPhone Strategy Until Now

Famously, Apple has eschewed segmenting the iPhone’s market. There are lots of reasons this could be the case, but I think the simplest explanation is also the correct one: the iPhone 5 is the first iPhone that Apple believes is “good enough”.

When a product category is brand new, the first few offerings are always deficient. They’re too slow, too big, missing features, compromised, etc. But, this being technology, the improvement is remarkably rapid. Most of this improvement is at the high-end, but soon it is possible to make a mid-range offering, and then a low-end. However, as long as the market is still immature, the leaps in quality year-over-year are significant and, more importantly, perceptible to average customers.

In the case of the iPhone, the 3G was clearly better than the 1st iPhone (enclosure notwithstanding), as was the 3GS relative to the 3G, and the 4 to the 3GS. Ultimately, Apple feels it was the iPhone 5 that is “good enough,” as seen by their willingness to finally make a mid-range version.

The “good enough” threshold is a dangerous one for the integrated innovator, as that is when modular substitutes start to catch up in the overall experience. While the iPhone retains lots of advantages and strong lock-in, to not offer a second, lower (not low) priced iPhone would be a mistake.

If the iPhone 5 is “good enough,” then it makes sense to sell a lower-cost version as soon as practical.

In fact, the primary mistake Apple has made, if they made one, was in determining exactly where the “good enough” line is at. The iPhone 4S is arguably “good enough” and could have been the basis for a mid-range model last year. Apple thought otherwise though; I would imagine a not insignificant factor is that the iPhone 5 is the first iPhone with a fully Apple-designed SoC, the A6.

Regardless, the line has been set; clearly we won’t see a truly low-priced iPhone until Apple can include iPhone 5-level technology at a price they are comfortable with.

So What is the Price?

The fact the 5C needs to be sold in both subsidized and unsubsidized markets makes the pricing tricky.

$0, though, is problematic from a branding perspective. While a new phone, heavily advertised (unlike the old iPhone 4) and sold for $0 would move an incredible number of units, it would also create consumer expectations around $0 and associate Apple with “cheap.” Apple is very hesitant to go there. $99 makes more sense. This point on branding applies to the unsubsidized cost as well; in Asia, in particular, the iPhone’s biggest selling point is brand prestige, not apps or user experience.

How is This Strategy Different?

It is true that Apple has been selling multiple iPhones for a few years now; right now they sell the iPhone 5 for $650/$199, the iPhone 4S for $550/$99, and the iPhone 4 for $450/$0. However, while this does capture some customers further down the demand curve, I think that the overall demand for “old” iPhones is much lower than demand for “new” iPhones.

The 5C, on the other hand, will be about as “new” as an iPhone can get, particularly with it’s colorful enclosures. Even if it’s priced the same as an iPhone 4S or 4, it will sell many, many more units because of stronger demand.

I expect the 5C to be a massive hit, not just internationally, but also in the US and other subsidized markets. This suggests a significant drop is the iPhone average selling price, but a big bump in top line revenue. The margin impact isn’t clear.

A “new” iPhone at the same price points as the “old” iPhones will sell many more units due to higher demand

What about the iPhone 5S?

The 5C clearly targets two iPhone growth opportunities: unsubsidized markets, and price-sensitive customers in subsidized markets. However, there is one other huge opportunity that Apple has always been reticent to target: enterprise.

The implosion of RIM and fragmentation of Android are increasingly leaving the iPhone as the default choice of more and more enterprises, and it’s in this light that the rumored fingerprint sensing technology is particularly interesting.

Most corporate laptops require two-factor identification. Previously, this meant a key card, although most now use the TPM chip with a separate password. Phones have been managed; IT departments can require a strong password, and remotely wipe a device, but there is no way to do 2-factor authorization, even though smartphones are just as much a computer as the laptops used 5 or 10 years ago.

In this light the fingerprint scanner is very useful: a fingerprint + password = 2-factor authentication. I could absolutely see the 5S being the first Apple product to not just infiltrate the enterprise from the ground up, but to be actively encouraged and even required by IT departments.

0 comments:

Post a Comment